It wasn’t until Edmund, my second son, was almost four months old that he was finally well enough to leave the hospital. During his stay, it had become apparent that he had intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), as well as physical disabilities. A hospital social worker had helped us complete the paperwork to register him as a person with a disability with the Social Security Administration.

No longer a newborn, our baby came home. For a while the financial costs to our family were mitigated. We received $70 a month in SSI income, which didn’t reimburse much of his costs, but was nothing to sneeze at. More importantly, Medicaid served as a secondary insurance to his primary insurance. We received reimbursements for his many doctor visit co-pays, help with home nursing services, and durable medical goods. We were grateful for the help, and still adjusting to our brand-new lives as parents of a child with multiple intensive disabilities. We didn’t look closely at the details or we would have known better.

Nearly a year later, a visit to the local Social Security office enlightened us. They informed us that the money and Medicaid payments we received were predicated on a mistake. Because Edmund had been at a hospital when we registered him with Social Security, they had a record of him living in an “institution,” that is, the hospital. We’d updated his address, but the fact that he was living at home was not recorded. He could get SSI income and Medicaid if he were living in an institution. However, since he was living at home, our income and assets disqualified him from SSI and Medicaid.

It turns out that raising him at home turned out to be far more expensive for us than institutionalizing him would have been. This is an example of what is known as Medicaid’s “institutional bias.” The peculiarities of Medicaid’s coverage encourage institutionalization for people with I/DD instead of community-based or home-based care. Medicaid is required to cover people in skilled nursing facilities, that is, institutions. It is not required to provide services to people with the same disabilities who live at home or on their own—services known as HCBS (Home and Community-Based Services). If states decide to cover such people, they do so by choice.

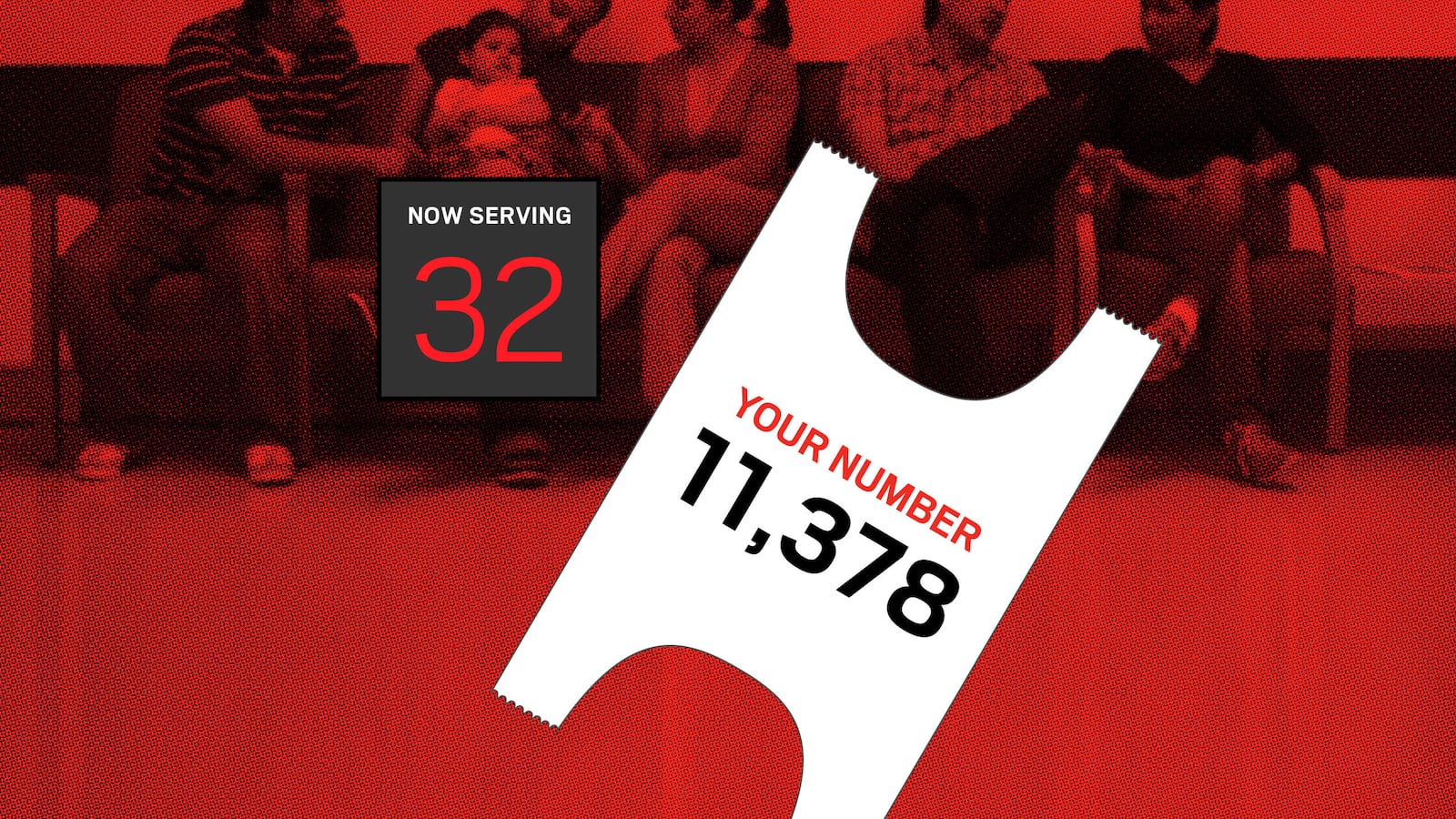

Edmund’s disabilities are such that he is considered to require an “institutional level of care.” (This phrasing is a bit odd, since he is not in fact institutionalized and we wouldn’t dream of institutionalizing him.) Since we raise him at home, our best option for help with his medical care above and beyond what our insurance will cover is what’s known as a “Medicaid waiver.” Such waivers vary from state to state, and within the same state there can be many types of waivers. Such waivers allow people to receive Medicaid benefits in HCBS settings regardless of income. So our family is set, right? Not so fast. Literally. Because Medicaid is not required to cover HCBS, because a waiver is not an entitlement, there are long waits for waivers. The particular waiver we’re waiting for? Right now, the waiting list is five years long.

We are by no means alone. As of 2012, there are over 523,000 people across the country on Medicaid waiver lists; over 309,000 of those people have I/DD. So we all wait and wait and pay and pay.

The system is beyond byzantine. Many states have multiple waiver programs. Not only can people with the same level of disability in two different states receive very different levels of benefits, but even within the same state, “two kids with the same disability might get very different services depending on what their assessed needs are,” Amie Lulinski, director of rights policy at The Arc, told The Daily Beast.

You might think that the reason Medicaid does not require coverage of HCBS is because institutional care is cheaper. This is, on average, incorrect. In our home state of Maryland, the state paid $418,756 per person in an institutions in 2011, yet only $42,999 per person annually on HCBS waiver programs. Unlike Maryland, national costs for institutionalization as opposed to HCBS do not differ by an order of magnitude. The difference is nonetheless drastic: $220,119 and $44,453, respectively, on average per person annually. The reasons to prefer HCBS to institutions are not simply that most families want to be with their loved ones and people with I/DD comparatively thrive in HCBS settings. HCBS makes clear financial sense.

The waiver waitlists are long enough if you live in one state without moving. If you move from state to state, however, the wait begins again. Barbra Driskill-Scherer is the mother of 9-year-old Gunnar, who has I/DD. After five years of not receiving services in California, her family moved to Virginia. Her wait for services started again. She has now been on the “urgency” waiting list in Virginia for 3½ years. “The waiver would help with the expenses to purchase medical adaptive devices for his use at home that he is able to utilize at school, such as a voice output device. It would also help with the extra costs such as diapers and PediaSure,” Driskill-Scherer said. “Respite care would be nice, too.”

HCBS waivers began in the 1980s. They were demanded by disability advocates and families who were reluctant to institutionalize their loved ones, given the new evidence that showed how detrimental institutionalization can be to people with I/DD. Waivers were also encouraged by states and the federal government who saw them, rightly, as a cost-cutting measure.

Now, however, it seems that an implicit contract made by the state to families when the waivers were instituted (if you care for your loved ones with disabilities at home or in the community instead of institutions, we’ll still provide the financial backing we always have) is being broken. Ari Ne’eman, president of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, whose organization strongly supports HCBS waivers as a “high priority,” told The Daily Beast, “wait-lists have become a way of shifting the costs of service provision on family. States know that families of people with disabilities will go to extraordinary lengths to keep loved ones from being institutionalized even without necessary service and supports.”

The Supreme Court’s 1999 decision in Olmstead v. L.C. held that institutional bias was not only an unjust segregation of people with disabilities from the larger community, but “confinement in an institution severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individuals, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement, and cultural enrichment."

Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa, a longtime disability advocate, has made HCBS a priority, a Harkin aide told The Daily Beast. Harkin introduced the Community Integration Act earlier this year. Based on the principles outlined in Olmstead, the act would eliminate Medicaid’s institutional bias and spell out the requirements for states to provide HCBS. The bill remains in committee in the Senate. An identical House bill is also still in committee.

Of course, the reason such waiting lists exist is that funding everyone would be a financial burden states could not bear. But that leaves states to pick and choose who gets support, based partially on certain criteria, and partially on first-come first-serve. We have a patchwork system in which some people are covered, and others wait and wait.

Ne’eman disagrees that providing services to everyone currently on waitlists would be a devastating financial burden to states. He points out that nine states have abolished such waitlists. “Any care that can be provided in an institutional setting can be provided at home, either in the family’s home or an apartment in the community,” Ne’eman notes. “It’s better for people with I/DD, and far more cost effective. Waiting lists can be eliminated. It’s just a question of will.”