Danny Manupassa sells everything the paranoid might need. As the director of PI-Products, he offers infra-red cameras, reinforced, security-focused doors to stop burglars armed with electric drills and saws, and even professional bug-sweeping services to find hidden microphones in cars.

But this thirtysomething entrepreneur’s main business—the one that has led to him being the center of a cross-border investigation into organized crime—is selling privacy-focused mobile phones.

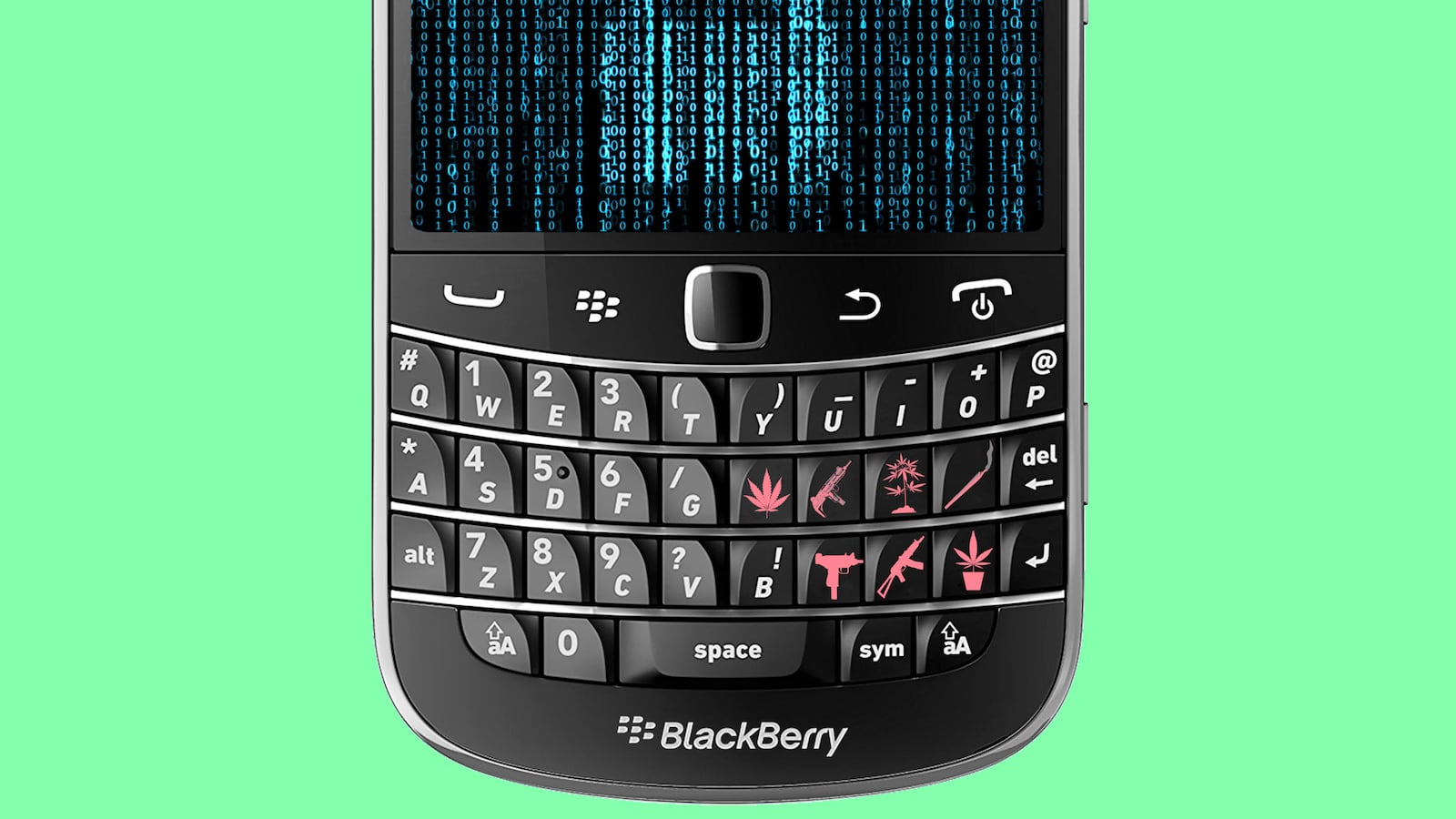

These types of phones have been linked to a high profile gangland execution in Australia, the largest ever shipment of automatic weapons in the U.K. detected by the police, and New York’s most prolific cannabis operation. So-called PGP phones, which sometimes even have the camera or microphone removed, are custom BlackBerry or Android devices that allow users to communicate with relative security. Manupassa’s phones have been linked to assassinations, armed robbery, money laundering, and other serious crimes, according to the Dutch authorities.

A Daily Beast investigation shows the widespread use of these devices by serious criminals, connections between crooks and some of the people that sell the phones, and the intense rivalry playing out across the industry.

“It's like the criminals started using the technology then decided to try to take it over,” one secure phone industry source, who asked to remain anonymous to avoid retaliation from some of the companies, told The Daily Beast.

A SkySecure and MPC advert on news site vlindercrime.

vinderscrime.nlOn the face of it, Manupassa’s BlackBerrys look like any other, with their distinctive QWERTY keyboard and basic display. Under the brandname Ennetcom, however, many of these phones come with PGP, or Pretty Good Privacy, an established system for encrypting emails. All communications also run through Ennetcom’s own infrastructure, making getting ahold of the messages that much harder.

“For us it doesn’t matter if you are a government organization, a corporation or a private person. We stand for security and privacy and therefore supply the same security solution to all our customers,” an archived version of the company’s website reads.

The phones are not cheap: Manupassa’s customers have to pay between 1,200 and 1,800 per year for a PGP device. Other companies offer even more features: SkySecure, seemingly one of the larger firms, includes a “duress password,” which can be entered to surreptitiously wipe the device, and Ciphr provides a “vault” for extra-protection of data stored on the phone.

Manupassa is far from alone in this space. A dizzying number of companies offer these sorts of phones all across the world: Phantom, Global Data, Encrochat, Secure Mobile, PublicPGP, PGPClass, Elite, Fortis Iceland PGP, and many more. Some companies simply sell re-branded versions of other firms’ devices, muddying exactly who really developed a particular phone, and who is responsible for selling it to particular customers. The firms, and the people behind them, all promise the same thing, though: to keep messages secure.

To be clear, some of these companies will be legitimate businesses, trying to provide a service to customers who are looking for private and secure communications. But others are more nefarious.

"Many of them are cloak and dagger operations; you can't talk to an owner. There is no CEO. There is no corporation,” Geoff Green, the owner of Myntex, another secure phone company, told The Daily Beast.

As with ordinary email, people using one provider can communicate with someone else signed up with another firm. Sometimes though, secure phone companies will supposedly add rivals to so-called blacklists, cutting off that bridge between different customer bases, as a means of intimidation against smaller companies. Green claimed SkySecure did this to Myntex several times. A representative of SkySecure denied knowing anything about Myntex, and told The Daily Beast “there are some third party companies that we open communication with but they need to meet stringent security standards.”

Green also complained of other companies creating ‘fake news’ posts, likely to discredit the competition. In a related case, MPC, another secure phone firm, previously offered to pay this reporter to write an “honest review” of their device.

Pressure between competitors can be focused on expanding territory as well. The industry source said secure phone firm Ciphr has approached resellers of other devices in an intimidating manner and tried to convince the vendors to switch sides. Ciphr did not respond to a request for comment.

Another source familiar with the industry, which The Daily Beast granted anonymity to speak candidly about sensitive business tactics, said some vendors had been warned about selling devices on another firm’s claimed turf.

“People connected in the underworld are given a piece of the distribution pie for each region,” the industry source said. Criminals allegedly provide financial backing for running at least one of the firms themselves, they added.

And the bullying tactics extend digitally too. Some of the companies allegedly bombard each other with distributed-denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, which flood a target with so much internet traffic that their website or other servers crawl to a halt.

“There are attacks on one or more providers every day,” the industry source said. “It’s providers attacking the competition or retribution,” the source added. (Although not necessarily an indicator of being a DDoS attack victim, a number of the large secure phone companies have DDoS protections in place, according to online records).

An advert for Encrochat's device on a crime news Twitter account.

Twitter/@misdaadnieuw2In April of this year someone hacked Ciphr, and published a searchable database of customer records online. At the time Ciphr blamed SkySecure for the data breach; SkySecure denied any involvement. The customer data came with a short step-by-step guide for how law enforcement might use the information to locate criminal suspects.

Indeed, it is clear that many of the secure phone industry’s customers include serious organized criminals. As well as the phones being connected to large scale drug trafficking operations and weapon smugglers, members of the notorious Kinahan gang in Ireland—which has entered a bloody feud with the rival Hutch outfit, leaving a trail of bodies in the past year—use the same sort of devices, according to local media reports.

Crucially, some of the encrypted phone firms, or at least a number of their resellers, are seemingly aware of this customer base, and have marketed their products on sites specifically visited by criminal communities.

MPC, EncroChat and SkySecure have all had adverts on vlinderscrime, a now defunct, crime focused news site, according to archived versions of the site. This makes sense, judging by a March 2015 post from Martin Kok, the cheeky-faced, former serious criminal who ran vlinderscrime: “I see on various crime sites these things [encrypted phones] are offered for sale because many of their future clients are also criminals. Advertising on a site where bicycles are offered does not make sense for this type of company,” he wrote.

Kok was killed by a gunman last year in the parking lot of a sex club. Shortly before his death, Kok met with a representative from MPC, according to a translation of a previous statement from the company.

“The events that unfold after both our rep and Martin left the [sex club] have now been widely reported,” the statement read.

Neither MPC or EncroChat responded to a request for comment on the adverts on vlinderscrime, and a representative from SkySecure said the advert was not their own, and did not come from any of the company’s known affiliates.

“Actions such as advertising on crime news sites is a contravention against their distribution agreements,” the representative wrote in a text message.

After this reporter previously published the name of one company’s owner, the person sent a flurry of threats.

“Do you realize the people you are fucking with?” they wrote in one email.

***

Manupassa’s secure phone business did not last. In April of last year, Dutch and Canadian authorities shut down Ennetcom, seized its servers, and arrested Manupassa on suspicion of money laundering.

Targeting the encrypted phone networks and their resellers appears to be an established tactic of law enforcement agencies around the world. But their approach is still somewhat controversial.

“Per se, these devices are perfectly legal,” Dennis Miralis, a criminal defense lawyer who has represented those who sell similar devices, told The Daily Beast. Miralis said Australian authorities, acting on intelligence from foreign law enforcement agencies, attempt to disrupt the flow of PGP phones by picking them up at the border.

In Manupassa’s case, after Dutch authorities seized Ennetcom’s servers they pushed a message out to all of the firm’s phones: if you’re, say, a doctor, lawyer, or other non-criminal user of the devices, please get in touch. No one responded to the message, even though, according to court records, Ennetcom had some 20,000 users.

Instead, due to how Ennetcom devices and servers handled encryption keys, Dutch authorities were able to decrypt a wealth of previously private messages. A Canadian judge ruled investigators could not simply dig through the trove of data looking for tips, however, but only a specific slice of communications.

According to the Netherland’s Public Prosecution Service, investigators have found messages between suspected criminals, including communications related to assassinations, armed robbery, drug trafficking, money laundering, attempted murder, and other organized crime.

But the trade goes on.

“Special promo for Ennetcom former customers,” a post on a rival encrypted phone seller’s Facebook page read after the bust.