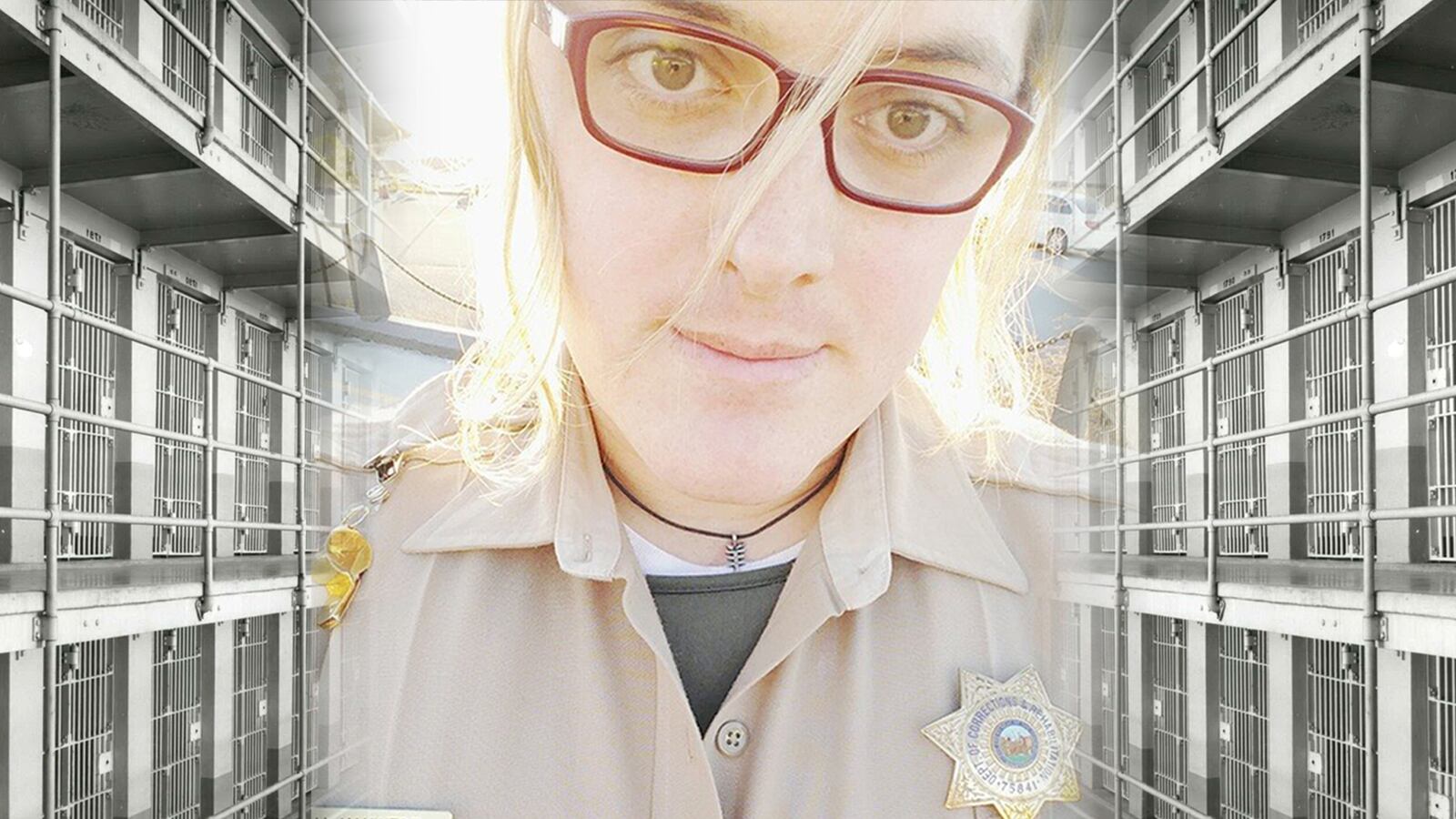

There are 24,000 correctional officers in the California prison system. Only one is transgender.

For almost eight years, Mandi Camille Hauwert, 35, has been a CO at San Quentin State Prison, which houses, among others, wife-killer Scott Peterson, serial killer Charles Ng, and “Dating Game Killer” Rodney Alcala. During her first five years on the job, the officers and inmates at the prison knew Mandi as Michael. Then in 2012, she began publicly transitioning to female.

Later this month, Hauwert, who has been undergoing hormone therapy for 2½ years, will undergo sex reassignment surgery to complete the process. Part of what has to be one of the smallest minority groups in America, Hauwert, the subject of a recent photo essay by Professor Richard Ross of UC Santa Barbara, spoke to me about becoming a woman while supervising male prisoners in a maximum security prison.

Q: You seem somewhat perplexed that anyone would want to read about your life.

Hauwert: It’s interesting to me that the simple fact I exist is so surprising to people. It’s not like I’m even the only transgender correctional officer in this country. There are others.

Really? How many?

Well, I actually don’t know any others here in this country. I’m in contact with two trans officers up in Canada, but really, the only time I’ve heard about transgender correctional officers in the U.S. is when they’ve been fired or there’s some kind of lawsuit happening.

What did you do before you started working in the prison system?

I was born in Oxnard, California, and grew up in small tract house in Port Hueneme, just down the road from the Seabee Navy base. My father is a government employee; he works for the Department of Defense. I was in Junior ROTC in high school, and joined the Navy in May 1999, at age 19. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, I didn’t know if I was ever going to transition, and it was a way to kind of get away from everybody and everything in my life at that time. I worked as a Damage Controlman, which would be equivalent to a civilian firefighter. It’s a super-macho job. Most trans women, before they come out, tend toward very masculine jobs and activities. You’re not really doing it to prove to others that you’re masculine; you’re doing it to prove to yourself that you are. Because you know something’s different on the inside.

I served four years in Yokosuka, Japan, just south of Tokyo. I had a girlfriend, someone I met in the Navy, and we were planning to get married, have children, have a family. Obviously, none of that worked out. I had come out to her a year after we were together, but we were still going to get married. I don’t know what we thought our relationship was going to be like, and I don’t think she thought that I was ever going to transition. I’m not actually interested in girls in that way, so for me it was more doing what I needed to do to look normal and not get kicked out of the military for being gay.

And how did you end up in corrections?

My girlfriend was planning to stay in the Navy, and I was going to be a Navy husband and follow her around. Typically, the wife follows the husband, but I was actually preparing myself for that role, in the opposite direction. I needed to stay mobile, so a lot of the jobs I took on were not careers. I came back home and worked private security, I was a video game tester, I worked for a tile-setting company. It turns out I’m really bad at setting tiles.

My girlfriend wanted to see me do something more with my life than just odd jobs, so I started looking around. Since the age of 14, I had been doing a martial art called wing chun kung fu, and my sifu (sensei) worked for the CDCR (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) with the Youth Authority. He was the one who suggested corrections to me. He felt I would be good at it. I entered the academy in August of 2007, after about eight months of background investigation, physical exam, psychological testing, and that sort of stuff. There were 700 or 800 questions on the psych exam you had to answer over three or four hours, and two of them asked whether or not you feel, or have ever felt, like you belonged more as a member of the opposite sex. I said no to both.

You spent five years working as a male correctional officer before becoming a female one. Tell us about the “transition” leading up to the transition.

I started working at San Quentin in December 2007, but didn’t come out until August 2012. For those first five years, I just kind of isolated myself and became incredibly depressed—I’d go to work, then go home and play video games and eat and go to sleep. I was on my own up here, no real family or friends nearby, and so I started to collect female clothing and whatnot; stuff that I would wear outside when I felt comfortable enough. Eventually, I wanted to be able to portray myself as a female more effectively. I had learned a little bit about makeup from my ex-girlfriend, and basically I just kind of started to experiment with different things. I found a hairdresser that was willing to work with me, to grow my hair out long enough to do something with when I wasn’t at work, but when I was, I could pin it up or put it behind my ears.

After about 4½ years of doing this, it started to bleed over into me wanting to express that femininity at work, but to do it in a subtle way so that hopefully nobody would say anything. So, even though I would wear makeup at work, I would wear a very light eyeliner, or a light lip gloss. People started to notice, especially the female officers. Some of them thought I was a goth.

How have the other officers responded to your transition?

Initially when I came out at San Quentin, there were obviously a lot of people who were completely surprised. I had been working the night shift—10 o’clock at night to 6 o’clock in the morning—which I think allowed me to get away with wearing little bits of makeup without anybody saying anything. I would often be posted at the main staff gate, where the officers check in, and during the shift change between 5 and 6 am, there’s a lot of heavy foot traffic going through there. I guess at some point, somebody noticed. Maybe a week or so later, I got a call that my supervisor wanted to have me in his office. He pulled in the other supervisors, and they basically asked what’s with the makeup, and my quick response was, “I’m transgender,” which was kind of the first time I had said it out loud. Then I had to basically sit there for the next 40 minutes or so explaining what “transgender” meant—they thought maybe I was telling them I was a crossdresser, they had no idea. So, they went over the female grooming standards—length of fingernails, style of hair, amount and type of makeup—then they gave me a card for EAP (Employee Assistance Program) and suggested I talk to a therapist.

I’ve been out at work for almost three years, and in that time, I’ve heard all kinds of really bad things. Stuff I probably should have filed [complaints] on people for. But at the same time, my strategy has been to kind of weather the storm, so that people will see that I’m just like everyone else, that there’s nothing to stress about, nothing to worry about.

What is the difference between working as a male officer versus working as a female officer? Do you do anything differently? Do the inmates under your supervision relate to you differently?

The honest answer is, I really don’t even know. As you transition from male to female, as you create and build and construct your identity as a woman—and it literally has to be constructed, not from thin air, but from the pieces that were always laying dormant in your mind—you’re letting go of little bits of your masculine self. And as you let them go, you no longer associate certain memories with being male or female. It’s actually really hard to think about how people related to me as a “guy” before my transition.

My biggest issue at work has been that people continue to refer to me as “he.” They call me “sir.” Someone who is not transgender would probably say, “What’s the big deal?” But what they don’t realize that we have been lying to ourselves and everyone around us our whole lives, so when you finally break free and start to express yourself honestly, being called a he sort of delegitimizes everything. They’re basically telling you that all the suffering you went through doesn’t matter, and every time they gender you incorrectly, they’re basically erasing your ability to self-identify.

Where are you currently at in your transition process?

I have 20 days until my gender reassignment surgery, although I prefer the term “gender confirmation.” I’ll be out for six weeks, and I’m having the surgery done by Marci Bowers, one of the world’s leading gender reassignment surgeons, who happens to be trans herself. The most incredible part is that as of last year, transgender services are now covered by my insurance. So, it’s perfect timing for me.

And your family? Where are they in all this?

When I initially came out as transgender to my parents, I tried to soften the blow by telling them that my girlfriend liked me to dress up in girl’s clothes. About a month later, I just spilled the entire can of beans. They looked at it as me having killed their son. My sister has been incredibly supportive from the beginning; she kind of accepted me after I put on a little fashion show for her and she saw how happy it made me.

My mother knew another trans person from a club she used to hang out at, and after this person came out as a woman, her family completely disowned her. Anyway, this girl ended up committing suicide because of it, and after that, my mother started to talk to me again. I always felt a little guilty that it took somebody dying for that to happen. My father doesn’t normally address the situation; that’s just kind of how he deals with things. I come from what you’d call a hugging family, we’re not afraid at all to show affection to one another, and I don’t get as many hugs from him as I used to, for sure.

The good news is that in 20 days, they’ll be up here with me for my surgery, and I’ll spend my recovery at their home in Southern California. I’ve been on a diet, and I’ve lost 35 pounds. People are already saying I look a lot thinner.