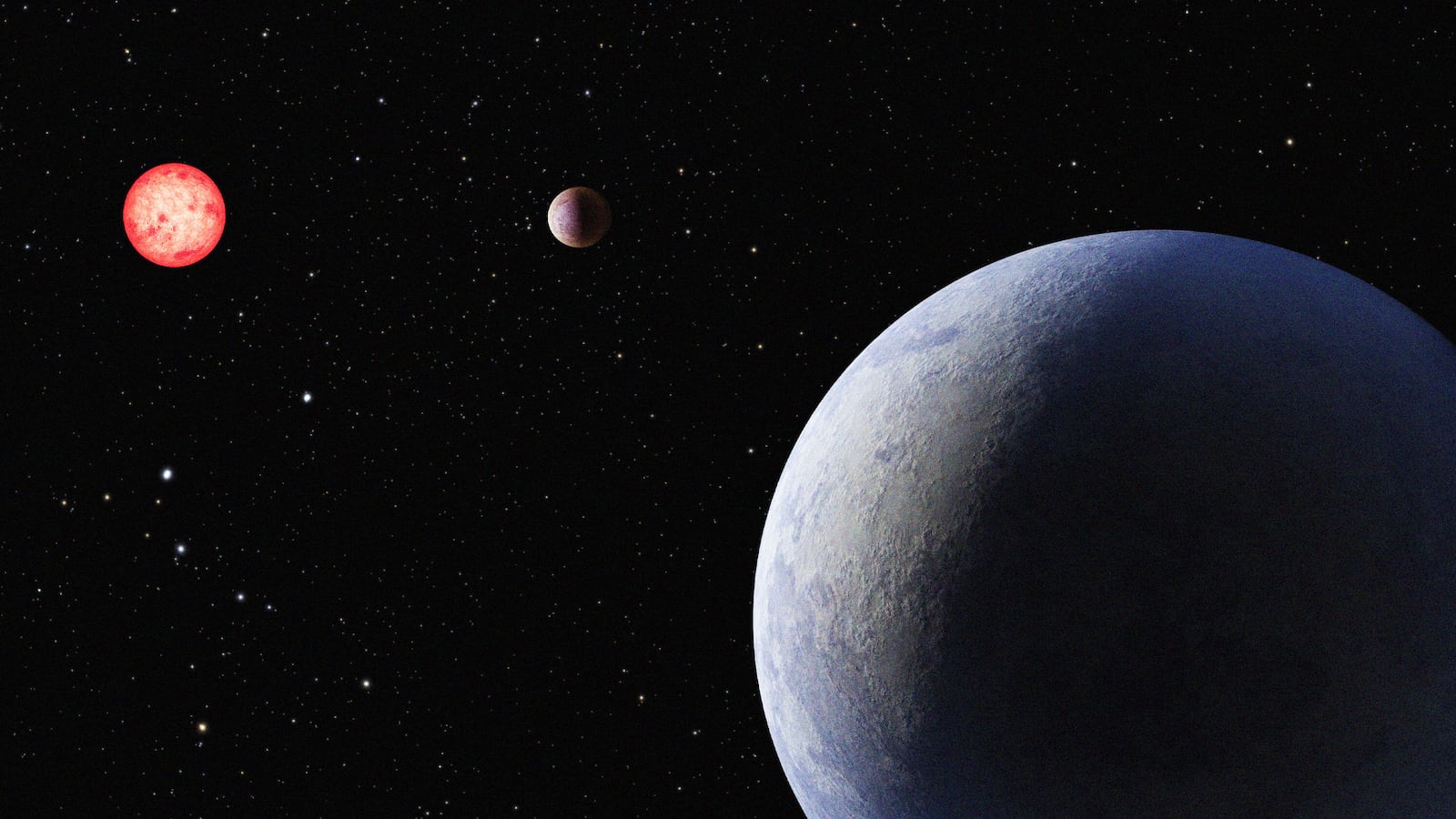

Astronomers are desperate to know what happened to Venus. Now, thanks to the recent discovery of the hot gassy planet’s virtual twin—LP 890-9 c, an apparently rocky, wet, Earth-and-Venus-sized planet orbiting a red dwarf star 98 light-years from Earth—those astronomers might finally have a chance to crack the mystery wide open. The problem is, right now there’s just one telescope capable of surveying this twin.

You’ve probably already heard of it by now: the James Webb Space Telescope. “JWST observations of LP 890-9 c have the potential to provide critical new insights,” a team led by Jonathan Gomez Barrientos, a Cornell University astronomer, wrote in a new peer-reviewed study that was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

But the JWST is in really high demand, and the line of researchers waiting to use it for their own investigations feels like it’s expanding at the same rate as the universe itself. And it remains to be seen whether the NASA-organized committee that doles out time on the $10-billion telescope agrees with Barrientos and his coauthors—and decides those insights are worth it.

Venus, the second planet from the sun, isn’t just Earth’s neighbor. It’s roughly the same size as Earth—and rocky, like Earth is. But while Earth evolved into the wet, breathable planet we know and enjoy, Venus apparently got so hot that its oceans evaporated. Poisonous carbon dioxide vapor then blanketed the planet, trapping the heat and making everything even hotter: a process of runaway global warming that gives climatologists here on Earth nightmares.

Why Venus got hot and toxic while Earth stayed relatively cool and liveable (for now) is one of the big mysteries of the solar system—and one with immediate implications for us as we pump more and more carbon into Earth’s atmosphere and risk our own greenhouse-gas calamity.

“The Venus-Earth divergence is one we must understand if we are to learn why planets like Earth can sometimes be habitable for billions of years and sometimes become uninhabitable, at least for our kind of life,” David Grinspoon, an astrobiologist with the Arizona-based Planetary Science Institute, told The Daily Beast.

Maybe Venus cooked owing to the eruption of huge volcanoes. Maybe a surge in the sun’s intensity tipped it into runaway heating. A leading theory is the planet is just slightly too close to the sun to stay cool and stable. It is, in other words, at the volatile edge of what astronomers call the “habitable zone” around a star.

We might be able to solve the mystery of Venus’ past by sending a whole lot of probes to the hot planet and taking lots and lots of samples, an effort that could take decades and cost billions of dollars. Or we could find a planet that’s around the same size as Venus, similar in basic composition and also in a similar position relative to its star’s habitable zone—then get a good reading of its atmosphere.

So it was cause for celebration when, last year, astronomers peering through a telescope at the SPECULOOS Southern Observatory in Chile discovered LP 890-9 c. They soon learned LP 890-9 c may or may not be in the throes of its own runaway climate change. The Chilean telescope is powerful enough to have found LP 890-9 c by looking for the planet’s silhouette as it passed between its star and Earth; yet it’s not powerful enough to determine exactly what’s happening in the planet’s atmosphere.

For that, we need to point the JWST at LP 890-9 c. According to MacDonald, it’s the only instrument currently in use that can do the job. “These are very challenging measurements to make, so even with JWST we would need multiple observations,” he said.

To get a good read on LP 890-9 c, Barrientos, MacDonald and company—or some other team of astronomers—would need to point the JWST at the planet at least three times, but preferably seven or so, scanning different wavelengths of light in order to measure different gases: oxygen, ozone, water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen dioxide and nitrogen.

The exact mix of gases in LP 890-9 c’s atmosphere should describe its present, and possibly hint at its future. A high concentration of carbon dioxide would be a strong indicator that a runaway greenhouse effect is already underway, and the planet is in trouble—just like Venus was all those eons ago. A more Earth-like mix of gases might indicate LP 890-9 c has a chance of ending up more like our own planet.

It could go either way, if the leading theory about Venus’ past—the habitable-zone theory—holds true. In terms of its proximity to its star, LP 890-9 c seems to be “in the sweet spot between Earth and Venus,” according to MacDonald.

If LP 890-9 c is managing to hold onto an Earth-like atmosphere despite how close it is to its star, it might lend credence to alternative explanations of Venus’ toxic evolution. Maybe there’s more to Venus’ past—and, by extension, Earth’s past—than an accident of proximity to the sun. By the same token, maybe LP 890-9 c “can tell us why the Earth stayed habitable,” MacDonald said.

That, in a nutshell, is the argument Barrientos, MacDonald, and his team plan to present to the JWST committee that decides who gets time with the uniquely powerful instrument. They get to make their case in October. And if the committee says yes, the team could start surveying LP 890-9 c next summer.

If the committee says no, Barrientos’ team might have to wait to study LP 890-9 c. Fortunately, new telescopes are getting better, fast—so they might not have to wait too long. “Currently JWST is the only way to try to characterize LP 890-9 c’s atmosphere,” Janusz Petkowski, an astrobiologist and expert on Venus at MIT, told The Daily Beast. “However there are other facilities under development that could potentially join the hunt.”

Several of these very-large telescopes are scheduled for completion this decade.