MEXICO CITY—One German millionaire posed outside her house holding up a piece of history; an ancient tool crafted from volcanic rock, and dated to as long ago as 1,000 B.C. Behind her, a huge Aztec statue stood alongside several other archaeological artifacts.

The Mexican government argues that these centuries-old pieces of cultural heritage belong in the nation’s museums.

Over in Europe, they are seen as cute collectibles. In a single sale in 2019, the German collector Manichak Aurance—who was so happy to show off her booty on film—auctioned off 94 artifacts.

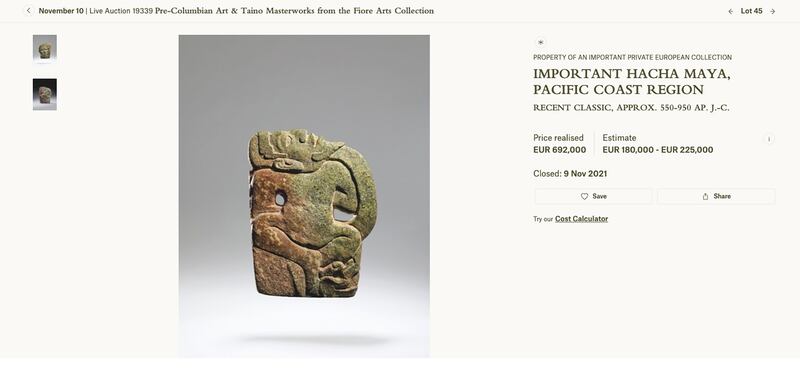

The sales continue. Earlier this month, the prestigious Christie’s auction house in France put up 72 pre-Columbian pieces that the Mexican government had specifically asked it not to, going so far as to call the auction “illegal.” Most of the pieces went up for sale anyway, including a stone Mayan carving called “Hacha Maya,” depicting a bearded man with his head thrown back and struggling with a rattlesnake, which was sold for $800,000 to an unknown buyer.

A few days after the collection was made public on Christie’s website, the Mexican Embassy in France said in a statement that it had contacted the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs to share its concern about the auction, essentially stating that Mexico’s “national heritage” should not be up for sale.

A stone Mayan carving called “Hacha Maya” up for auction at Christie’s.

Christie’sIn the letter, the embassy also argued that the commercialization of archaeological artefacts encourages transnational crime and creates favorable conditions for looting cultural assets with illicit excavations. In the eyes of Mexico, every piece of archaeological relevance belonging to the region that is currently abroad is considered stolen, given regulations against trafficking of its cultural heritage that have existed since the 1800s.

In a written statement to The Daily Beast, a Christie’s spokesperson wrote, “We devote considerable resources to investigating the provenance of works we offer for sale, and have specific procedures, including the requirement that our sellers provide evidence of ownership. In the case of the upcoming sale, these checks have been carried out and we have no reason to believe that the property is from an illicit source or that its sale would be contrary to French law.”

Mexico’s current administration has doubled down on its efforts to recover the nation’s archaeological heritage from abroad. Since President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador took office four years ago, the country has recovered more than 5,000 archaeological, historical, artistic and ethnographic items.

Most recently, in September of this year, an auction hosted by Bertolami Fine Arts in Rome was suspended after Mexico claimed the pieces offered belonged to its cultural heritage. The art house decided to cancel the event, and Italian authorities launched an investigation into the matter.

“Our history is not for sale,” said Mexico’s Minister of Culture Alejandra Frausto during a press conference immediately after the Christie’s auction. “These artifacts are not luxury decorations for a house, they are part of what makes Mexico a cultural nation.”

Efforts to stop the sale of Mexico’s cultural heritage in Europe appear to be slow-moving. On Nov. 17 and 20, Millon and Drouot, two art houses in France, auctioned off several ancient artifacts, including an Olmec mask for around $4,000 that had belonged to a “Mexican diplomat in Monaco,” according to a brochure.

The Daily Beast reached out to the Mexican representatives in Monaco but no one was available for comment.

Fragment of Mayan stela.

Stephane De Sakutin/AFP via Getty Images“The main problem is the demand, the buyers. For the most part they are wealthy Europeans who feel powerful and sophisticated,” Daniel Salinas Córdova, a Mexican archaeologist and researcher living in Germany told The Daily Beast.

“The issue [with ancient artifacts] is the same as with drugs trafficking. Without paying attention to who the buyers are, it will be very difficult to stop the trafficking and commercialization of these pieces,” Córdova, added.

But getting to the bidders is almost impossible, as auction houses are not obligated to share information about the buyers. So far this year, Europe alone has had 23 auctions with a total of around 1,000 Mexican ancient artifacts sold.

Mexican law has prohibited the extraction of cultural goods from Mexican soil for more than 100 years, but many of the countries in which the artifacts end up after being illegally extracted and trafficked didn’t pass legislation on the issue until 1970, when UNESCO published an international treaty stating that all cultural property belongs to its country of origin and could not be imported, exported or transferred.

All of the artifacts on sale today are described as having been obtained before 1970 to prove their legality.

The goods, as Córdova explained, were for the most part extracted between the 1920s and 1970, from known and unknown archaeological sites around Mexico by “impoverished families” who often got paid a few pesos for the obtained pieces by brokers who ended up selling them for several thousands to clients abroad. Córdova said this practice is still happening, but on a much smaller scale.

“Some buyers think they are protecting the artifacts by acquiring them and taking them out of Mexico, but in reality they are privatizing our history and denying access to many Mexicans to even learn those pieces exist,” Córdova said. “It is very sad that we as Mexicans can’t get to know how many pieces are at the houses of rich and powerful Europeans and we only learn about them when they die and the pieces go up for auction again.”

A new auction with at least a dozen ancient artifacts from Mexico is set in France to go up on Dec. 3 at Million auction house. Mexican authorities have already tried to stop the event, but the pieces are still listed, with expected prices as high as $200,000.