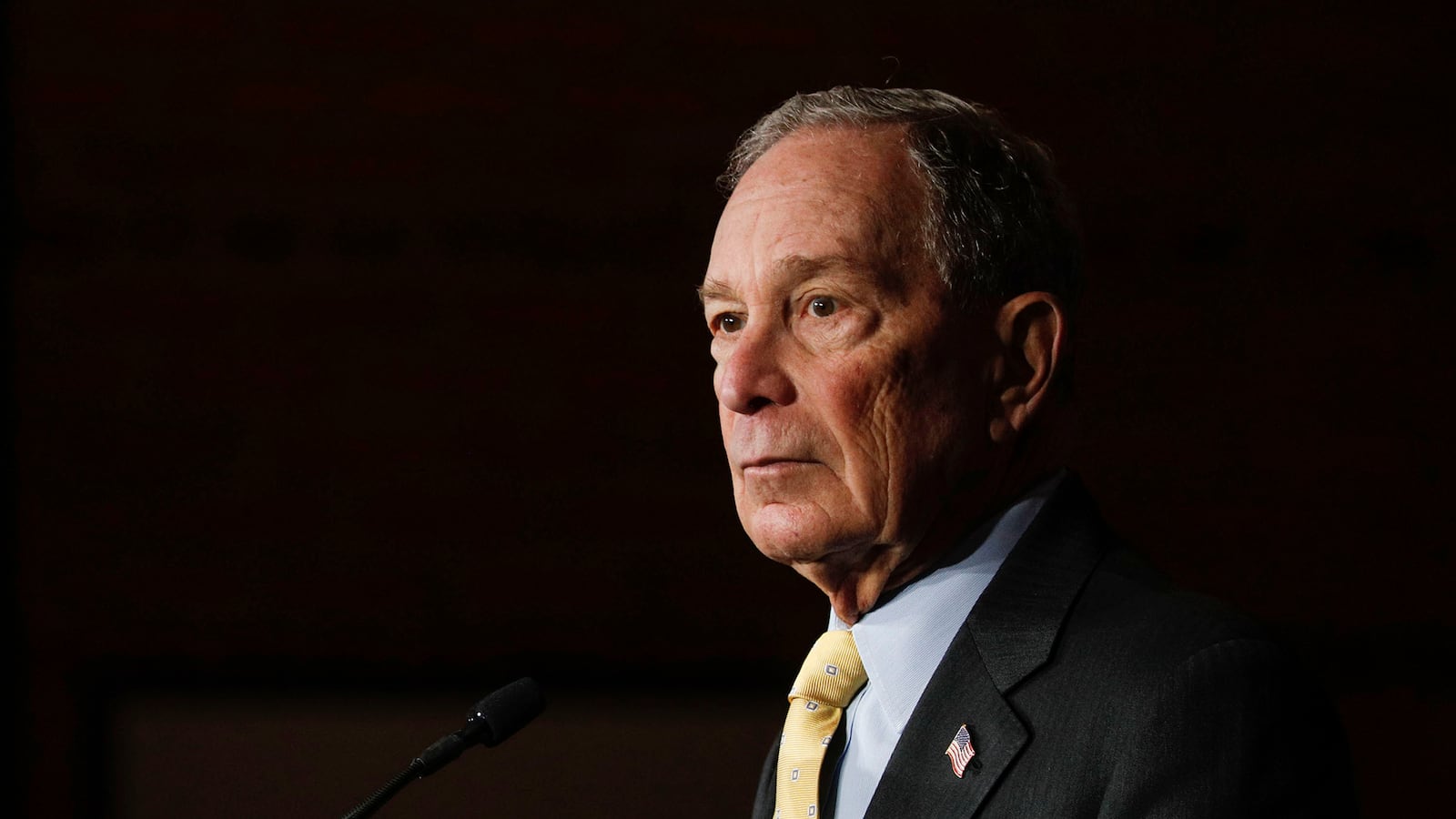

The oligarch running for the Democratic presidential nomination, former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg, appeared to rationalize Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine by referencing America’s own maculate history of expansion and conquest.

Bloomberg’s remarks, flagged Tuesday by Washington Post columnist Josh Rogin, were made to the Aspen Institute in February 2015. Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea was about a year old at the time, and sparked a crisis in U.S.-Russian relations that has yet to relent.

During the appearance, Bloomberg, referencing the host of geopolitical issues from Iran to China—and what he calls the “crazy Islamic world”—where Russia possessed influence, said, “You have to have Russia as an ally in these things.”

“Nobody thinks Russia should be in the Ukraine and trying to take land from an independent and sovereign country,” Bloomberg said, meandering away from a question on the unique experience of being a mayor.

“But if you really think about it,” he continued, “what would America do if we had a contiguous country where a lot of people in that country wanted to be Americans. Do Texas and California ring a bell? We just went in and took it.”

Russia’s ties to Ukraine are historic—Sevastopol, on the Black Sea, has been critical to the Russian navy since Catherine the Great’s 18th-century invasion—but so is Ukraine’s independent identity. Bloomberg glossed over the fact that the plebiscite in Crimea occurred after Russian soldiers, deniable as so-called “Little Green Men,” had already occupied critical positions on the peninsula. The then-new U.S.-backed government in Kiev had declared the Russian-sponsored referendum a violation of Ukranian law, none of which Bloomberg mentioned.

“OK, I’m not suggesting that Putin is doing a good thing, or that he should be allowed, but we did this,” Bloomberg continued. “Two-hundred years ago, but we did this. You want a warm-water port? Guantanamo Bay ring a bell?”

Guantanamo Bay, on Cuba’s southwest coast, was for decades used as a coaling station by the U.S. Navy under lease by a compliant local government. Fidel Castro overthrew that government and insisted on a U.S. departure that Washington has refused for six decades despite the Navy no longer needing Guantanamo strategically. The U.S. sends the Cuban government rent checks, to honor the terms of the hundred-plus-year-old lease, that Castro refused to cash in protest of the U.S. refusal to depart.

“Sphere of influence? One of the reasons that Putin has reacted the way he did is that there was a movement to have NATO be right on the Russian border,” Bloomberg continued, analogizing Russia’s rejection of NATO expansion to the U.S. refusal to tolerate Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba, 90 miles off the Florida coast.

NATO expansion in the '90s, the nadir of Russia’s geopolitical influence since the days of Catherine if not Peter the Great, was not designed by the Clinton administration to subjugate Russia. But influential voices in Russia for a generation have nevertheless viewed it as a humiliation demanding redress, Putin included, given NATO’s history as an explicit bulwark on Russian designs in Europe. What both Bloomberg and Putin overlooked is the appetite from former Soviet bloc countries, thanks to their experience of Russian domination, to join the western military alliance.

Yet Bloomberg’s remarks are likely to call into question his affinity for strongmen, something he shares with Donald Trump, the president he disdains and seeks to dislodge.

Like Trump, the former mayor has praised China’s Xi Jinping as “not a dictator”—Bloomberg’s remarks came during Xi’s repression of protests in Hong Kong—something that raised eyebrows considering his extensive business interests in China. Later in Bloomberg’s Aspen remarks, he spoke about meeting with India’s Hindu nationalist prime minister Narendra Modi to discuss a “non-profit consulting firm.”

Another similarity with Trump is audible in Bloomberg’s 2015 remarks. The billionaire referenced Russia’s “3000-mile border with the whole crazy Islamic world.”

“You’ve got to do something. Russia can’t just go into an independent country and take it over,” Bloomberg continued, cautioning that he was making an observation about the complexity of world affairs. “On the other hand, at the same time, the federal government [has] to understand, that you also need Russia for a lot of things that we want to do.”