TIJUANA, Mexico—After fleeing tear gas shot at the U.S. border, Carlos González confessed confusion and second thoughts about the caravan that carried him to doorstep of his dream: life in the United States.

The 40-year-old corn farmer from Honduras, wearing a pink breast cancer awareness hat and an orange work vest, had hopped on the caravan of Central American migrants figuring it would facilitate his entry into the country. It set out from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, on Oct. 12 and for five weeks he could hope and dream—especially as the caravan pushed past police barricades and crossed through closed borders in Guatemala and Mexico.

But the U.S. border has proved impossible so far for the more than 7,000 migrants anxiously arriving in Tijuana, where they’re waiting in the squalor of a small baseball stadium-turned-tent city. It’s just a stone’s throw from the border they hope to cross, which many could not imagine would be so difficult.

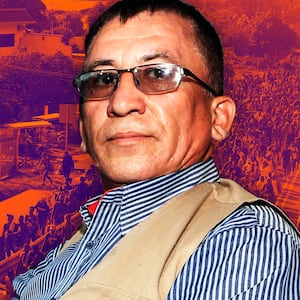

Carlos González traveled to Tijuana with the caravan of Central American migrants. He expressed regret with his decision, saying the U.S. border was tougher to cross than he expected.

David Agren“I thought it would be easy,” said González, who traveled north with his wife and two children, ages 4 and 3. He said his family was planning to sign up with Mexican officials for voluntary repatriation.

“We’re here alone, hungry, unprotected. My daughter is sick with diarrhea,” he said from a street by Tijuana’s El Chaparral border crossing, where he hoped to make a little money washing cars. “I don’t want to lose my kids, lose my life.”

Scenes of migrants fleeing tear gas shot their way by U.S. Border Patrol brought condemnation and accusations of excess. The Sunday protest was peaceful, several participants told The Daily Beast. The protesters, including women and children, first encountered Mexican police, but detoured around them and headed toward the border. There, according to U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, they breached the fence.

The migrants say they wanted nothing more than to ask for answers as to why they were unable to cross the border or make asylum claims.

But the tough treatment at the border brought home a rude reality for many migrants in the caravan: that their idealized vision of the United States—a kind and just country willing to welcome people wanting nothing more than to work or seek safety—has put obstacles in their path.

Asylum claims are increasingly hard to make as fewer than 100 migrants a day are allowed to approach the border crossing and receive a “credible fear” interview, the first step in the process.

At the Chaparral border crossing, Central American migrants and Mexicans hailing from states rife with violence lined up to put their name on a list to have their claims heard.

Jeffrey Renderos, 31, put his name in a ledger and received a ticket with the number 1655. Renderos, a bearded Honduran who fled gang threats and arrived in Tijuana six months ago, figured he would wait at least a month to have a hearing—though he wasn’t complaining. He couldn’t contain his scorn for the caravan, however.

Jeffrey Renderos, 31, has put his name on a list in Tijuana to apply for asylum in the United States. He expressed dismay with the protest of caravan travelers at the border, saying it wouldn't help asylum seekers.

David Agren“If they acted like civilized people, it would be different,” he said. When asked why he held such a poor opinion of fellow Hondurans, he responded, “You saw the way they clashed with police?”

The arrival of so many caravan travelers and images of clashes with police have exposed an unseemly underbelly of xenophobia. A poll in the newspaper El Universal showed 49 percent of Mexicans saying caravans shouldn’t be allowed to cross the country.

“First Mexico and Mexicans,” read one comment in response to the polls.

“It’s anti-poor people,” said Javier Urbano, a professor at the Ibero-American University in Mexico City, who studies immigration. Immigration from the United States, Canada and Europe was been welcomed, he said—in contrast to Central Americans—as such migrants tend to be whiter and come from wealthier countries middle class Mexicans say they want to emulate.

Some migrant activists have questioned the wisdom of convening caravans, saying the tensions in Tijuana were predictable—especially as so many migrants arriving in one place would inevitably strain resources.

“What we’ve worried about is the closing of the border, the (colder) climate in northern Mexico… and organized crime,” said Jorge Andrade, director of a collective of migrant shelters that stretch the length of the country.

Andrade expressed dismay with the “excessive” response to Sunday's protest, but added, “Unfortunately there are groups [of migrants] there that want to cross the border under these circumstances.”

Luis Corrales, 35, a waiter from San Pedro Sula, didn’t expect any problems in the protest. He said the march set out to seek answers from U.S. officials, though he acknowledged some had hoped they could make their case to border patrol agents and enter the United States.

Women and children were walking at the front of the march, he said, “to see if they would let them enter.”

Corrales, wearing a yellow soccer jersey, expressed few complaints with the camp, where he sold single cigarettes to fellow migrants. He thought the caravan’s experience crossing into Guatemala and Mexico would prove the template for the U.S. border.

But now, “I’m done with the United States. I’ll stay here.”

Others in the caravan admitted dismay with the impatience of their colleagues.

“This was their idea and their actions are going to hurt us,” said Javier Pineda, 31, a construction worker who put his name on the asylum list at the border. “We’re going to wait our turn. This is our dream.”