Born in 1829 near the Gila River in what is now Arizona, the legendary Indian warrior Geronimo was a Chiracahua Apache. The Chiracahua in the 19th century were a nomadic people who lived by raiding, trading, and a bit of hardscrabble farming in the mountainous lands of northern Mexico, and in the Arizona and New Mexico territories. It was against the forces of Mexico, not the United States, that Geronimo made his initial reputation as a frustratingly elusive warrior-raider-outlaw who struck terror and dread into the hearts of thousands of ordinary Mexican settlers, as well as other Indian bands. Later, American settlers came to feel just the same way about this fierce Apache.

Driven by a thirst for vengeance over the killing of his wife and three young children in 1851 in a horrific act of brutality by Mexican troops, and later by other myriad betrayals—or perceived betrayals—by U.S. authorities, he wreaked no end of havoc over a wide swath of the Southwest. No question about it: Geronimo was a master of ambush, hit-and-run attack, deception, evasion, and all the other tactics we associate with guerrilla warfare. Atrocities of a quite grizzly sort were part and parcel of many of his “engagements.”

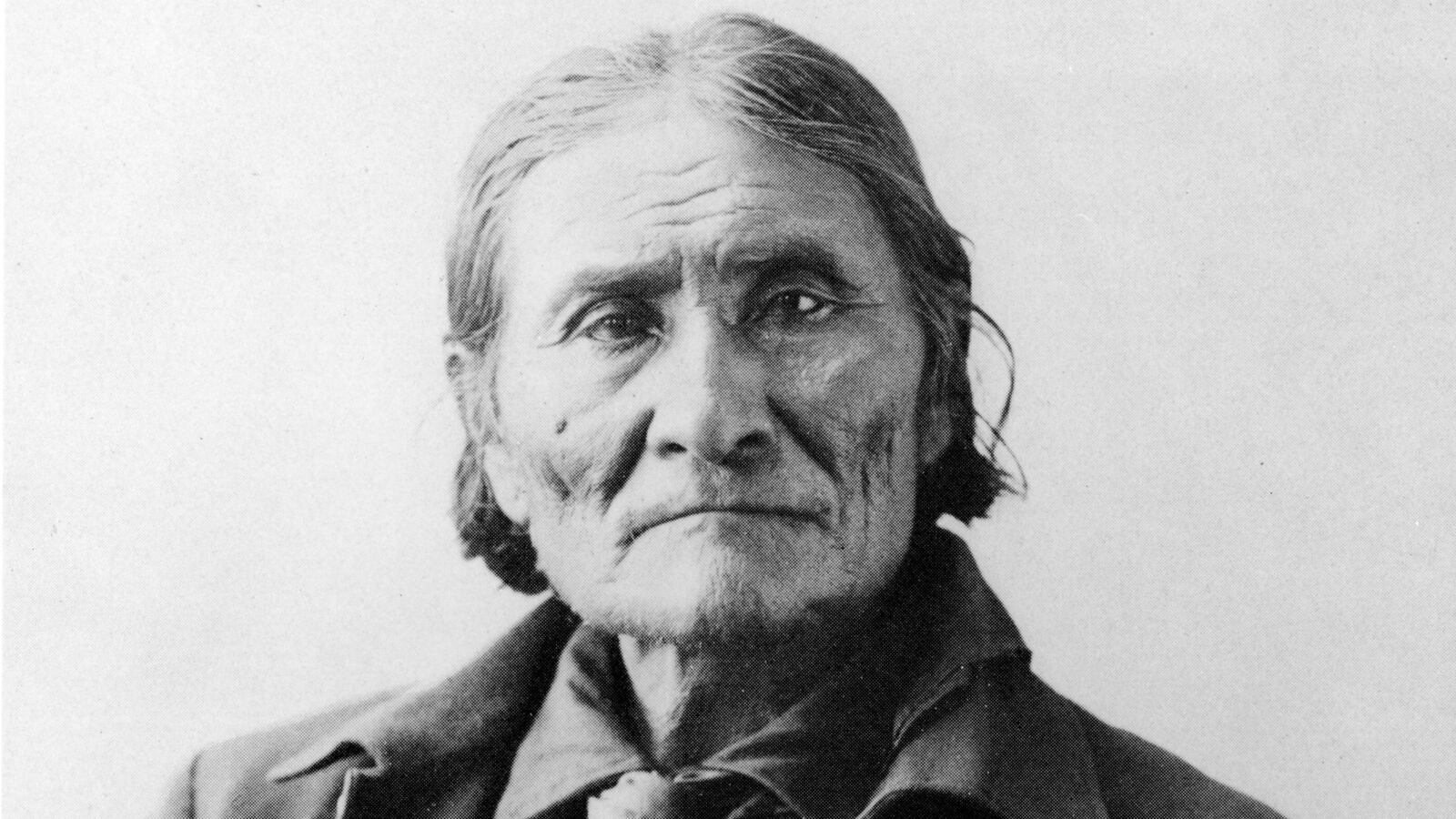

Leather tough, squat and muscular, with deep-set piercing eyes, Geronimo was capable of feats of exceptional endurance and martial skill even by the standards of the Chiracahua—and that’s saying a great deal, for they were truly Indian Spartans, groomed for war from childhood in some of the most unforgiving terrain in North America. He had that indefinable sixth sense that distinguishes gifted warriors from good ones. He could read subtle signs of an enemy’s presence on the hard Apache landscape with uncommon precision. And he could kill without compunction, using whatever implement was at hand, whether it was a knife, bow and arrow, a Winchester rifle, or simply a pair of hands. The Marines, who know a great deal more than most of us about such things, would call him (approvingly) a “hard-charging, trained killer.”

Mike Leach, an unorthodox college football coach of some distinction currently at the helm of the Washington State Cougars, has been fascinated by Geronimo since he was a boy growing up in Wyoming in the ’70s. He sees the Chiracahua raider as the last in a long line of Indian resistance leaders such as King Philip, Tecumseh, Sitting Bull, and Chief Joseph, who were determined to save their people and their culture. Moreover, Leach thinks Geronimo’s career offers important insights into the mysteries of strategy and leadership. It’s these insights Leach attempts to mine in his new book, Geronimo: Leadership Strategies of an American Warrior.

Leach fell in love—and awe—with Geronimo as a boy playing cowboys and Indians:

Geronimo was the best of [the Apaches]—he possessed a kind of greatness . . . Geronimo personified a life-way of excellence, and others around him rallied behind that excellence and followed him . . . He possessed great integrity and commitment because of his pride in being an Apache . . . He personified independence and assertive action. Geronimo and the Apache epitomize the American spirit.

Leach’s unbridled enthusiasm for his subject comes through on virtually every page, keeping this saga of betrayal and mayhem and courage and outrage pumping along at a heady pace. I found Leach’s book a clearly written survey of the hagiographic kind, written in the style and voice of the books on American heroes found in droves in the Young Adult sections in public libraries in the ’70s and ’80s.

It’s lively, too, if a bit gory at times, with ample quotations from Geronimo’s own autobiography, as well from some excellent memoirs of a few Chiracahuas who both raised hell and rode through it with our heroic leader. “We don’t fight Mexicans with cartridges,” Geronimo tells Britton Davis, U.S. Army officer, midway through the story, in a not-atypical attempt by our hero to be a flattering tough guy. “Cartridges cost too much. We keep them to fight your white soldiers. We fight Mexicans with rocks.” Hmm.

The book is often unintentionally funny, especially when it comes time to analyze tales of derring do. As a study in strategy and leadership, though, it falls flat on its face, and hard. Part of the problem is with the structure, which is awkward, to say the least. The author plops down one- and two-sentence “lessons” in large type here and there into the main narrative, and concludes each chapter with a few discrete, very short commentaries. This takes away virtually all the pain involved in integrating strategic analysis with narrative for the writer, but it’s tough, and often quite confusing, for the reader. The connection between the narrative and the lessons is often a bit hazy . . . or is it me?

For instance, after narrating a disastrous 1882 engagement against a battalion of Mexicans, which resulted in heavy casualties and the abduction of Geronimo’s own wife—he lost several out of a total of nine over his long career—we are told: “Effective leadership requires clear-headedness and even temper. Listen to and believe your instincts.”

Trouble is, as Leach tells it, our hero and his intrepid warriors were caught completely by surprise by the assaulting Mexican force, having been tricked by the local Mexican authorities into accepting hefty quantities of mescal several days earlier. Geronimo and most of his band had gotten themselves completely plastered, and stayed that way for several days before the Mexican onslaught. (Apparently, they ran out of rocks when attacked. Leach doesn’t say.)

At the end of another narrative chapter where Geronimo must engage in tortuous negotiation with a U.S. Army officer, we get this pearl of commentary:

The dealings between Geronimo and [arch-enemy U.S. General George] Crook remind me of the dealings between Reagan and Gorbachev during the Cold War. The catch phrase, which Reagan borrowed from a Russian proverb, was “trust but verify.” The idea was that even if information from your adversary seemed reliable, you’d better verify that it was accurate. That’s what Geronimo needed to do in dealing with bureaucracies. Bureaucracies are inefficient and dishonest—maybe not intentionally . . . but because there are too many moving parts.

Taken together, the commentaries do not present a coherent strategic vision, or distinctive Geronimoan “way of war,” as the military strategists are fond of saying. Rather, they form a kind of grab bag of trite and overused axioms, bromides drawn from a host of strategy manuals (and football coach pep talks?) penned by authors from the worlds of sports, business, and the military. We’re told: As leaders, embrace lore. Guard against betrayal. Treat all people with dignity. Try to anticipate what the opposition will do. Develop better systems and techniques than your adversaries. As a leader, you have to think about all of the people, not just one. (Many lessons and commentaries are in the imperative voice, but not all.)

But the real secret of the hero’s approach may have been revealed when Leach writes, with no small measure of truth, “Geronimo did whatever he wanted.”

Professional historians have tended to present Geronimo a bit more critically, and I can see why, considering some of the horrendous mistakes and decisions he made—a hefty number of them are even reported by Coach Leach in the book, but they don’t seem to dent his glowing views of his subject. The historians tend to see Geronimo’s concerns as being far more narrow and self-centered, his objectives more limited and temporal, than those of the many truly inspiring great war chiefs of Native American history.

Geronimo sought not so much to preserve a way of life for the Chiracahua as a whole—he was not a chief, and never aspired to be one—but to keep the party going for his own small band of followers, and that meant preying on the innocent, time and time again. He sought self-aggrandizement, and was extremely fond of killing. Brutally. Scores of Indians lost their lives, including Geronimo’s own family members, because of his carelessness and inattention due to excessive imbibing.

After the Mexican War of 1846, most of the Chiracahua’s territory fell within the confines of U.S. territory. As the Anglo population continued its inexorable expansion westward, the various Apache groups engaged in a series of wars against the U.S. Army before reluctantly agreeing in 1872 to retire to reservations. These are important wars worthy of serious study, but Geronimo’s role in those wars was not particularly significant. He was no Cochise or Mangas Coloradas—the two great Apache war chiefs he fought under. He often commanded as few as 30 men under arms. A leader on a rather small scale is what he was in the end.

Geronimo’s rise to prominence, and infamy, among white Americans began soon after the Chiracahuas and all the Apaches had surrendered and moved on to a large reservation at San Carlos, Arizona. Between 1876 and 1884, three times Geronimo and his small band of followers, seldom more than 100 souls in total, broke free, and proceeded to rain terror down wherever they traveled around the Southwest. During his last two years of freedom, he successfully evaded 5,000 U.S. soldiers as he crisscrossed rough terrain—no mean feat, granted. But he seldom engaged professional soldiers in battle. He preferred to go after civilians, virtually all guilty of two things: they weren’t Chiracahua, and they had good stuff to steal. ”Hundreds died as Apache raiders swept down on farms, ranges, villages, mining claims, and travelers to exact an appalling toll of plunder, destruction, mutilation, and death,” writes Robert Utley, whose book, Geronimo, is widely regarded as the definitive scholarly work on the man. “He shot, slashed, tortured, and murdered almost anyone he came across.”

After his surrender in 1886, Geronimo spent his final 22 years as a POW, the last of them at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where, with the permission of his Army minders, he became a kind of national folk-hero/curiosity as the star attraction in country fairs and exhibitions, posing for photos for a fee, selling the buttons off his coat, and participating in mock cowboy and Indian skirmishes, always under armed guard.

Given the scholarly consensus about the man’s actual history as opposed to his legendary role as great freedom fighter, I think writing a book about his strategy and leadership qualities would be a serious challenge, even for our most celebrated students of strategy, such as John Nagl, Richard Betts, or Tom Ricks. You can’t fit a square peg into a round hole. As for Geronimo, there’s not enough there there.

Leach is a crafty, gridiron coach who knows how to win. I admire his guts for taking a stab at writing a book about an important figure, who is, I think, important for rather different reasons than the coach would have us believe. Unfortunately, he’s just out of his depth in writing about what amounts in the end to military strategy. At one point in the Introduction, the coach opines, “history is hard to pin down.” Yes indeed, and I’m afraid that, in Leach’s book, Geronimo has slipped the noose one last time.