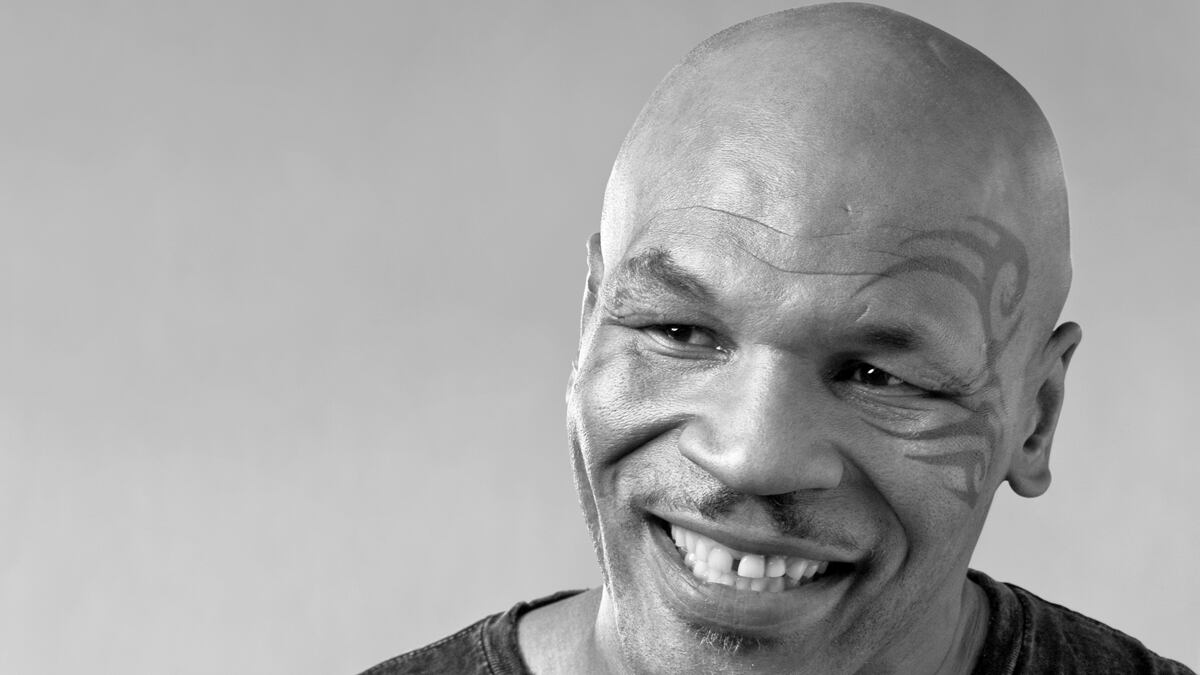

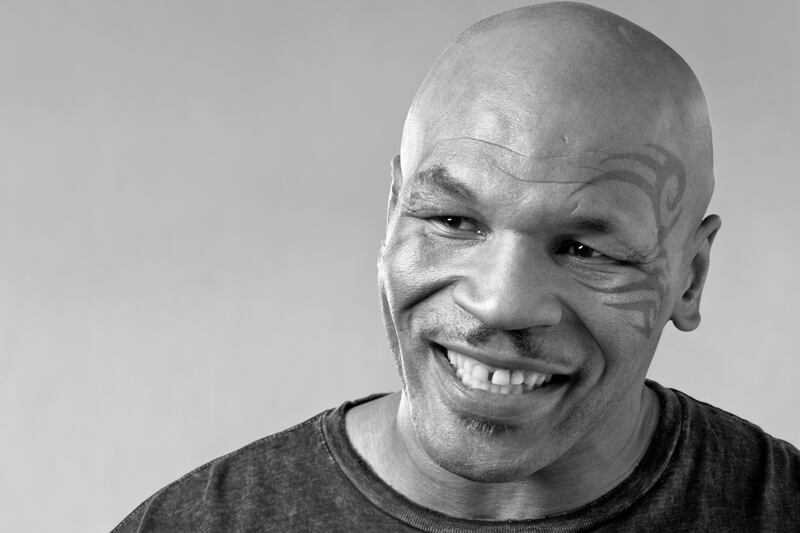

Mike Tyson is a marvel. Though he never lived up to his boundless fistic potential, he has thoroughly avoided the waters of oblivion and remains one of the most recognizable figures on the planet.

The man with mercurial mitts and pulverizing power has always been boxing’s drama queen. With the likes of his “I want to eat your children” comments and the ear-biting episode, Iron Mike always had a knack for transforming normal events into surreal supra-normal happenings. Now he is taking his penchant for theater to the theater.

Historically famous boxers such as Jim Corbett, Jack Johnson, and Jack Dempsey made part of their daily bread on Broadway and the vaudeville circuit. Tyson will continue that tradition when his one-man theatrical production, “Mike Tyson: Undisputed Truth” opens in Las Vegas on April 13 at the MGM Grand’s Hollywood Theatre.

Accompanied by music and videos, this live oral history will consist of a series of monologues on a variety of subjects including his mother’s death, winning the title, the rape conviction, and the loss of his daughter. But the leitmotif is sure to be Tyson giving voice to his incessant inner dialogue with Constantine “Cus” D’Amato, the man who long ago took up residence behind the fighter’s eyes. The guru who directed the careers of Floyd Patterson and Jose Torres, D’Amato trained Tyson from the age of 13 until he died in 1985.

In a recent conversation, an animated Tyson rehearsed some of the memories he will bring to the stage: “Cus loved tough guys, and was always thinking about violence. In time, I knew he would kill for me and I felt the same for him.” Tyson laughed softly. “That was the measure of love for me back then. He was the first person I ever trusted. I was this big and muscle-y kid and I’d walk around wearing this black jacket, like I was his body guard or something—never saying a word, looking mean and ferocious, ready to destroy anyone who just looked at him the wrong way.”

Though his trainer seldom complimented him in person, Tyson remembered, “Cus was always building me up when we met someone. After only five or so amateur fights, he would introduce me as this kid who was going to be the best fighter in history. It was embarrassing. It was crazy.” But as most boxing scribes would agree, D’Amato’s assessment of Tyson’s talent was far from crazy.

The strange duo would read books together like The Art of War and Zen and the Art of Archery. Everything was about mastering the fighting arts but with the firm conviction that “the way you fight is the way you live.” Tyson recalled, “When I told Cus that I came from a broken home, he thought that was great because he believed broken homes made for meaner, better fighters. And when I told him about the crime I grew up around, he’d say it was good because it would make you stronger and smarter.”

Pondering pugilistic technique, D’Amato and his pupil made scholarly studies of the films of all the greats. Some of their favorites were Willie Pep, Sam Langford, Ted “Kid” Lewis, Jack Britton, Harry Greb, and Sugar Ray Robinson. Tyson recalled, “One time I put my head down and told Cus, 'I’m a coward. I don’t have it in me to be like these guys. Look how many fights they had—all together something like 1,400. They would lose and come back. I can’t do that.’ Then Cus started hollering, ‘You see, those fighters are so great they even intimidate you from the grave. That is real intimidation—intimidation from the grave.’ ”

D’Amato offered many workshops on fear—how to bottle, control, and use it. Together, they worked at the art of freezing opponents in terror. Today, Tyson exudes warmth, but in his time, he had the glint of Achilles in his eyes and his body seemed to roil with a dark destructive energy. Many of the men he defeated could have been counted out long before they stepped through the ropes.

Tyson’s stories roll out of his heart and off his tongue with ease. When he talks, the pathos punches through and you get the sense of a man actively processing his gargantuan past. He confided, “There was the time I lost to Tillman in the Olympic Trials. I was so depressed. I couldn’t wait to get home and smoke some of the weed that I had hidden. But when I got there, the maid or someone had found it and there was Cus with the bag, holding it up and screaming, ‘This must be really good stuff—really good stuff—to get you to pass over the 400 years of slavery your people went through, when you could have been something.’ I felt like absolute [expletive].” Tyson recalled that D’Amato’s remonstrations that day were, for him, the first chimes of race consciousness.

Iron Mike was not always resilient in the ring; however, when it comes to absorbing the blows of life, there is no one with a better chin. Abject poverty, divorces, incarceration, suspension from boxing, hundreds of millions come and gone, addiction, the death of a child—he has been through it all and is still stepping forward. Indeed, to listen to him now one would think that the former boxer may be one of those rare birds in life who not only endures bad experiences but learns from them.

Randy Johnson, the director of this production, effused, “Mike is really articulate, bright, funny, and knows himself. It is one of the best directing experiences of my life. I have never worked with anyone who had such quick and immediate access to memories and authentic emotions.”

Tyson’s wife, Kiki, played a large roll in crafting the script of this redemption tale. She recalled, “Mike would tell me all these great stories. I would write them down. Then I would try to put them in his voice. I have known him so long that I had his diction down, but now and again, Mike would shake his head and wave his hand, ‘That’s a word I would never use,’ and we would go back and find another.”

Kiki continues: “The first thing that we want to do with the show is disarm the audience. Disarm them of all the preconceptions about Mike. They know him as this strong, fierce, tough guy, but in this performance they’re going to get the whole picture—the warm, emotional, and hilarious side of Mike.” One of the director’s favorite vignettes takes place with Tyson in rehab and jabbering to a fellow inpatient whom he mistakenly believes to be his doctor.

Tyson enjoyed acting in the movie The Hangover, but a one-man theatrical performance is new territory. I jabbed him, “Are you afraid?” “Damn right,” he answered. “Terrified.” Then it was the voice of the old man in his corner again. “But you know Cus used to say that to accomplish anything great you have to take risks. Everybody knows that, but then Cus would go on to say that the risk has to be of absolute, complete humiliation. It’s that fear of humiliation that makes you prepare, that gives you that edge.”