Half Full

Kurt Hutton/Getty

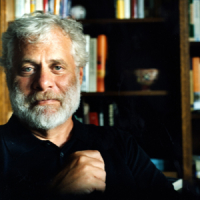

‘Milk’: Mark Kurlansky, Author of ‘Cod’ and ‘Salt,’ Focuses on Dairy in His New Book

Excerpt

A brand-new book traces the history of milk back 10,000 years.

Trending Now

Crime & JusticeUnshaven Luigi Mangione Shows Signs of Stress in Court

Crime & JusticeLuigi Mangione Judge Married to Former Healthcare Exec