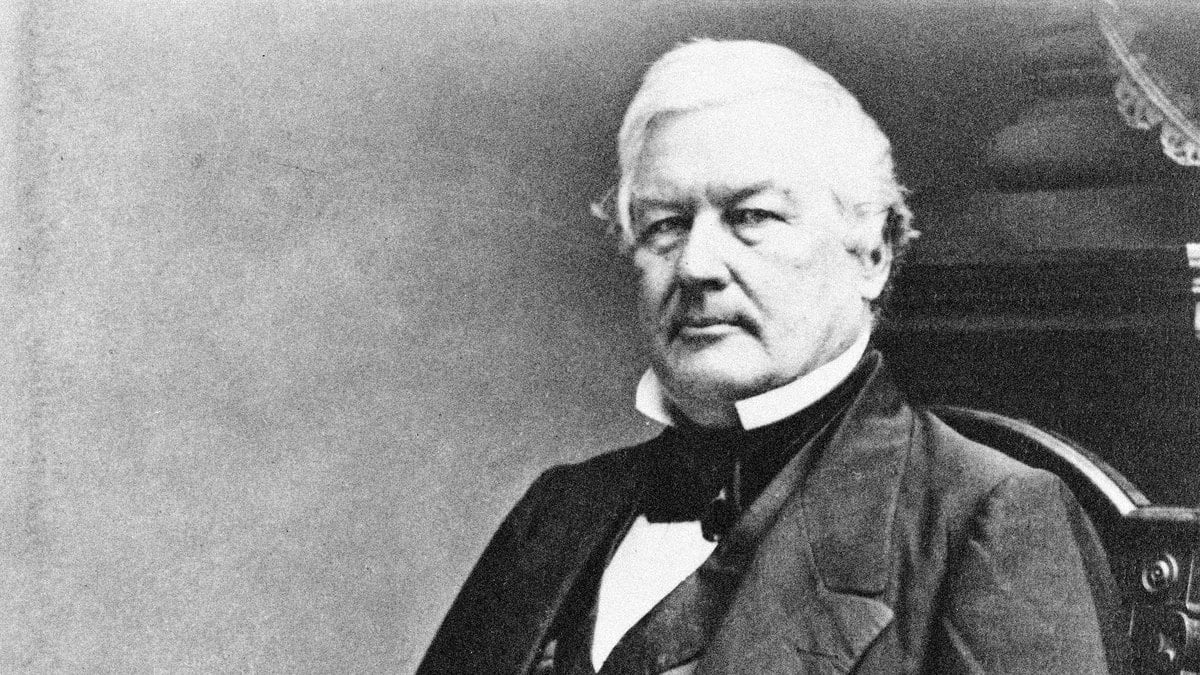

On the expanding list of canceled honors for the perpetrators of slavery and racism—think Andrew Jackson, Robert E. Lee, John C. Calhoun, and Woodrow Wilson—the name Millard Fillmore is notable for its very obscurity. If the 13th president of the United States is remembered at all, it is usually as the answer to a trivia question or the punchline to a joke about historical insignificance. Nonetheless, students at the University at Buffalo (part of the State University of New York) have persuaded the administration to remove Fillmore’s name from an Academic Center that includes faculty offices, dormitories, and a theater. A son of Buffalo, Fillmore was a founder of the university and its first chancellor. He was also the president who signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. And therein lies his disgrace.

Elected vice president as a Whig in 1848, Fillmore ascended to the presidency upon the death of Zachary Taylor in 1850. At the time, the United States seemed to be verging on dissolution over the extension of slavery into territory acquired in the Mexican War. Various compromises between the free and slave states had been proposed in Congress, most recently a package of bills sponsored by Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky. President Taylor had opposed the compromise as too favorable to the “Slave Power,” but Fillmore embraced it.

The most infamous provision of the Compromise of 1850 was the enhancement of the Fugitive Slave Act, first signed by George Washington in 1793. The original act, which left enforcement up to state courts, proved unenforceable when anti-slavery sentiment increasingly developed in the North, thus leading the southern states to demand a more effective law. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 accomplished that goal by federalizing the rendition of runaways. It created a new class of U.S. commissioners to preside over summary “removal” hearings, conducted without juries and with no right of appeal. Warrants from slave states were presumptively valid, to be executed by federal marshals, and alleged fugitives were not allowed to testify in their own defense. Commissioners received a $10 fee for each decision in favor of a slaveholder, but only $5 for setting someone free.

Many northerners, and not only abolitionists, considered the Fugitive Slave Act to be a form of legalized kidnapping. Some African-Americans, both fugitives and free, fled to Canada, realizing that the law offered them scant protection. Others vowed armed resistance. Frederick Douglass warned that the “only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers.”

Fillmore himself claimed to “detest slavery,” calling it “an existing evil” necessary to maintain the Union, but that did not keep him from making enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act a priority. Within weeks of passage there were 19 successful proceedings, with only two dismissals.

In 1851, Secretary of State Daniel Webster demanded the death penalty in a treason prosecution against 38 defendants who had resisted slavecatchers near Christiana, Pennsylvania. The government’s failure in that case (in which a slave owner had been killed) did not deter the Fillmore administration. Federal troops were repeatedly deployed to enforce the act, especially in cities like Boston where there was profound popular resistance. Fillmore celebrated the “triumph of the law” when a fugitive was returned to Georgia at bayonet point.

Fillmore was the first in a series of three “doughface” presidents—Northern men with Southern principles—who sought to accommodate slavery interests, including expansion into previously free territories. If he was not the most despicable pro-slavery politician in the antebellum era, a position for which there would be much competition, he was certainly among the most hypocritical.

The University at Buffalo announced the removal of Fillmore’s name as advancing its “commitment to fight systemic racism and create a welcoming environment.” It is improbable that many students had been aware of Fillmore’s crucial role in the re-enslavement of escapees, but it would be hard to continue honoring him once the full story became known. Fillmore was not merely the reluctant signatory of unfortunately necessary legislation. Nor did he simply express bigotry in his personal correspondence, reflective of the times, as did some other non-obvious cancelees, such as Flannery O’Connor. Damningly, Fillmore was an enthusiastic enforcer of one of the most racially oppressive federal laws in U.S. history.

It actually speaks well of the University at Buffalo that Fillmore was evidently the largest available target for protesters. The campus apparently has no monuments to treasonous generals, Ku Klux Klan leaders, or genocidaires, as grace so many other locales. Ironically, canceling his name probably generated the most attention Fillmore has received in over 150 years. Hardly anyone knew much about him before, and no one is likely to miss him now.

Steven Lubet is Williams Memorial Professor at the Northwestern University School of Law, and the author of Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial.