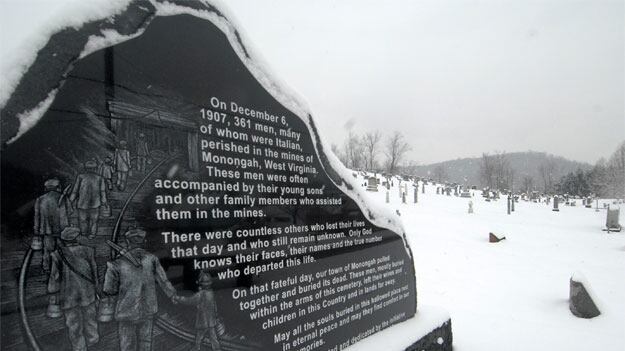

Considered the worst mining disaster in American history, this West Virginia explosion claimed just short of 1,000 lives on December 6, 1907. After methane ignited coal dust in two mines in the West Virginia town of Monongah, rescue workers tried to save the lives of any surviving coal miners, but could only work for 15 minutes at a time due to lack of proper breathing equipment. Some of the rescuers also perished after inhaling the poisonous smoke, leading to a reported 956 total deaths, many of whom were Italian immigrants. Stanley Urban was one of many the Monongah blast claimed, but his twin did not suffer the same fate. Peter Urban was the explosion’s only known survivor after he was able find a small fox-hole to shelter him from the toxic gases. He was found four days after the initial blast, lucky to be alive. But in an eerie twist of fate, approximately 19 years later, Peter Urban was killed in a different mine cave.

Dale Sparks / AP Photo

Four years after the opening of the Cherry Mine, named after its sleepy Illinois town, nearly 500 men and boys, and their three-dozen mules, went to work, just as they had on most other days. But on November 13, 1909, an electrical outage from earlier in the week forced the miners to light kerosene lanterns and torches to be able to do their jobs. Shortly after noon, one of the wall lanterns set a coal car, filled with bales of hay for the mules, ablaze. While about 200 workers were able to make their way to the surface, many remained trapped. A group of 12 brave men made six trips to rescue their fellow workers. But on the seventh rescue trip, they were all burned to death, contributing to the total 259 victims the fire claimed. Another group of 21 miners, however, built a makeshift wall to protect themselves from both the flames and poisonous gases. Known as the “eight day men,” the workers were able to survive on a pool of water leaking from a coal stream until a trip to find more water lead to their rescue on November 21.

AP Photo

Founded in 1901, Dawson was once one of New Mexico’s prosperous mining towns, but it has since become more like a ghost town, due in part to its first major disaster at Stag Canyon Mine No. 2. On October 22, 1913, an explosion that could be felt two miles away, took the lives of more than 250 men working in the mine. A dynamite charge had gone off, igniting coal dust and trapping and poisoning most of the miners inside. Of the 286 workers who arrived at the mine that morning, only 23 emerged alive. Though rescuers worked around the clock to find survivors, all they brought up were rows of bodies and two lost their lives as well.

New Mexico State University Library, Archives and Special Collections / AP Photo

On the morning of May 1, 1900, coal dust accumulating in a mineshaft in Utah unexpectedly exploded after an errant spark ignited it, leaving several hundred miners struggling for their lives. The blast could be heard in neighboring towns, but many residents initially believed the noise to be fireworks set off early in celebration of Dewey Day. Once those nearby understood that a disaster occurred, it took nearly twenty minutes for rescue workers to clear away the debris that blocked the entrance to the mine before they could even try to save lives. Two hundred men died in the explosion and nearly 50 rescuers also perished in the process. But some good did come out of the tragedy—the following year, coal workers had a strike, calling for better treatment and more safety in the mines. And by 1904, miners countrywide were striking for the same cause.

AP Photo

The Granite Mountain copper mine in Montana was believed to be a model of safety—its shafts were well ventilated and the North Butte Company was nearly finished installing a new sprinkler system. But it wasn’t completed soon enough—on June 8, 1917, 2,000 feet below ground, a fire broke out in the main shaft. The flames raged on for three days, eventually claiming 164 coal miners of the approximately 400 who showed up for work that day. It was the deadliest disaster in the history of metal mining and many were left husbandless and fatherless. Amusement parks closed, baseball games were canceled, and one of the city’s largest department stores invited widows to come in for clothes to attend their husbands’ funerals, one researcher on the subject revealed.

Stephen Hilger / Bloomberg News / Getty Images

There’s one Pennsylvania town that won’t stop burning. Over the past 30 years, Centralia’s population has dwindled from over 1,000 residents to fewer than 10. The decline began with a coal mine explosion in 1947 that left 111 workers dead. Essentially, the mining business stopped overnight, but the same did not hold true for the flames. In 1962, another blast went off and the coal is reportedly still burning beneath the ground of the desolate borough nearly 50 years later. In the 20 years that followed the second mine explosion, workers attempted to put out the fire—flushing the mines with water and ash and digging through the trenches to find the fire’s boundaries. But efforts continuously failed and by the 1980s, engineers determined that the fire could potentially spread over approximately 3,700 acres. More than 50 years, $40 million, and hundreds of destroyed lives and homes later, Centralia is now essentially a ghost town.

Don Emmert / AFP / Getty Images

Idaho’s Sunshine mine has been one of the world’s largest producers of silver since it was established more than a century ago. But in the early morning hours of May 2, 1972, a fire broke out in the otherwise prosperous mine. Unlike other mine accidents, more workers survived these flames than were claimed by them—166 men were rescued while 91 perished from smoke inhalation or carbon monoxide poisoning. Though the mine closed for seven months after the disaster, eventually many workers did return to the mine that has since gone on to produce more than 360,000,000 ounces of one of the world’s most sought after metals. So there is always a silver lining.

Ralph Crane / Time Life Pictures / Getty Images

West Frankfort, Illinois was rocked on December 21, 1951 when three explosions occurred in the Orient No. 2 mine in the quiet rural town of 12,000 people. Around 7 p.m. black smoke was seen coming out of the mine, and for days, 120 men were trapped in the 12 miles of wreckage as hundreds of their family members anxiously awaited news. More than 200 men worked tirelessly for nearly 60 hours to rescue the trapped coal miners, but the explosion’s vicious force claimed 119 lives. One man, Cecil Sanders, survived the explosion, despite being trapped for 60 hours in an area with little oxygen, and was rescued on Christmas Day—the one bright spot of hope during the event known as “the black Christmas.” Later, investigators found dozens of safety code violations, even though an inspector had finished a weeklong checkup nine days before the blast. This disaster, along with two other Illinois mining accidents, led to President Truman signing the Federal Coal Mine Safety Act of 1952 requiring annual inspections in certain underground mines and gave the Bureau of Mines the authority to penalize mine operators.

AP Photo

The explosion that occurred in the early morning of November 20, 1968 in the Consol No. 9 mine near Farmington, West Virginia, was so devastating it was felt nearly 12 miles away. A huge fire spread throughout the mine and 99 people were trapped, and only 21 men were able to escape in the hours after the blast. After a week of rescuers valiantly trying to fight the flames and continuous explosions, they were forced to give up and seal the mine with concrete. The 78 men left in the mine were killed and the effort to recover all the bodies took more than a decade. The widows of some on the men who were killed in the Farmington Mine Disaster lobbied before Congress and, in 1969, President Nixon signed the Coal Mine Safety and Health Act. This was the dawning of a new age in mining—changes included more annual inspections, mandatory fines for violations, and benefits for miners plagued with black lung disease.

Despite new health and safety standards enacted by the Coal Act exactly one year earlier, another mining disaster occurred not far from Hyden, Kentucky on December 30, 1970. Also known as the Hurricane Creek mine disaster, the blast killed 38 men in the truck mine owned by Charles and Stanley Finley. The rescue effort was hampered by terrible weather—a foot of snow fell on the roads that led to the mine at the time of the accident. The explosion could have been prevented—inspectors noted in the previous month that the small mine was an “imminent danger” because of the failure to control coal dust and electrical hazards. One miner who escaped just as the explosion was going off claimed to see primer cord, an illegal type of fuse, in the mine. The mine’s owner, Chuck Finley, went on trial for his negligent role in the accident, and President Nixon promised that the penalties afforded by the Coal Act would be more strictly enforced.

Emory Kristof / National Geographic / Getty Images

On Monday April 5, 2010, a blast rocked the Upper Big Branch Mine in Montcoal, West Virginia, killing 25 workers and leaving four more missing in the worst U.S. mining disaster in more than 20 years. Rescuers are still holding out hope to try to save the four men left trapped in the mine, but must first wait before drilling 1,000 feet into the earth to release the dangerous pent-up gases. One of the miners who heard the explosion said, "it was just like your ears stopped up and it's just like you're just right in the middle of a tornado.” The Upper Big Branch Mine produced more than 1.2 million tons of coal last year, and reports have surfaced of a staggering 57 safety violations in March.

Jeff Gentner / AP Photo

On January 2, 2006, West Virginia was the epicenter of another tragedy. The coal mine explosion in Sago, West Virginia killed 12 people, with one lone man surviving the brutal conditions. The first rescue crew didn’t arrive at the mine’s site until hours after the blast and rescuers had to wait 12 hours for the carbon monoxide and methane gas levels to subside before beginning their search. All 12 of the men were believed to have died from carbon monoxide poisoning, and after two days, only 26-year-old Randal McCloy was rescued from two miles below the surface but did not escape unharmed—he was carried out with kidney, lung, liver, and heart damage. The accident was made worse when botched communication out of West Virginia led the public to believe there were 12 survivors, instead of 12 dead, and the New York Times and The Washington Post were among the papers to lead with stories of a miraculous and false rescue. In 2008, the mine was closed permanently.

Dale Sparks / AP Photo