During an interview with a Catholic anti-abortion outlet this September, Lynn Fitch—the lawyer arguing the case that could effectively overturn Roe v. Wade—called reproductive freedom a “states’ rights” issue.

Fitch, Mississippi’s first woman attorney general, is undoubtedly aware of the historical associations of that phrase, which one local outlet noted has been “often invoked throughout Mississippi’s history, including in defense of slavery, segregation and the state’s now-defunct same-sex marriage ban.” Very nearly as a rule, the usage of “states’ rights” seems to presage a curtailing of civil rights, and Fitch’s effort to ban nearly all abortions in her state fits that pattern. It is a legal effort steeped in patriarchy and misogyny, twin oppressions that frequently come packaged with white supremacy.

Those connections likely sprang to mind for many earlier this month when a profile of Fitch mentioned her family’s 8,000-acre farm, known as “Galena Plantation,” aka “Fitch Farms,” where she spent childhood weekends horse riding and hunting quail. The site was originally owned by William Henry Coxe, whom one newspaper in 1894 described as “a rabid secessionist”; another Coxe property website says of the first Galena Plantation house, which was destroyed in the 1950s, that “bricks for the foundation and the chimneys were burned on the place by slave workman (sic), and the fine interior detailing was also the work of slave carpenters.” An African American genealogy site places the number of enslaved folks forced to labor at Galena Plantation at 104, and a 1971 article from Mississippi’s Clarion-Ledger notes “the slave quarters” at the farm “were so large it was mistaken for a village.”

Bill Fitch, Lynn’s father, apparently renovated that once-meager housing, and today it’s likely among the lodgings available to paying guests of Galena Plantation—a sort of Confederate Disneyland on the same site where Black folks were enslaved and subjected to abuses we will never fully know.

According to a 2005 article, Bill Fitch was “a civil war buff, especially when it comes to General Nathan Bedford Forrest.” The Fitch Farms-Galena Plantation website boasts that he “bought, transported, and restored Nathan Bedford Forrest’s old cabin home... complete with old Civil War and Nathan Bedford Forrest memorabilia.” It also indicates that “guests may retire for the evening in one of six recently restored Civil War-era cabins, one of which was once the home of Confederate General, Nathan Bedford Forrest.”

This brief description curiously omits some of the most notable information about who Forrest was known to be.

For starters, Forrest is today most widely recognized as the first grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, which was founded by former Confederates just months after the end of the Civil War—and the start of Black emancipation, at least in name—in 1865. Forrest is said to have praised the Klan campaign of harassment, intimidation, and terror against Black folks and its white supremacist aims by stating, “That’s a good thing; that’s a damn good thing. We can use that to keep the n----rs in their place.” He would oversee the KKK’s growth to nearly half a million members while leading the Klan until 1869, the same year the group was officially declared a terrorist organization by a federal grand jury. In 1871, congressional hearings concluded that somewhere between 20,000 and 50,000 Black folks were murdered from 1866 to 1872 by the Klan and its violent sympathizers.

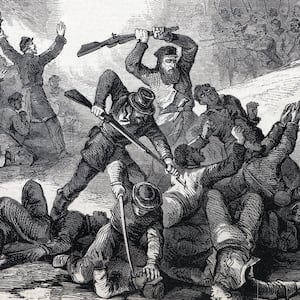

Also absent from the Fitch Farms-Galena Plantation recollection of Forrest is the notorious massacre of Black soldiers he led at Fort Pillow, in Tennessee, just along the Mississippi River. After Forrest and his troops had overtaken the fort, instead of holding the surrendered Union soldiers as prisoners of war, Forrest’s men went on a killing spree, taking particularly murderous aim at Black Union servicemen. Accounts of this pogrom are horrific. Mack Leaming, a white Union officer, would later write that “many of the colored soldiers, seeing that no quarters were to be given, madly leaped into the river, while the rebels stood on the banks or part way up the bluff, and shot at the heads of their victims.” He describes one Black soldier, who while attempting to surrender “seemed to be wounded and crawled on his hands and knees. Finally one of the confederate soldiers placed his revolver to the head of the colored soldier and killed him.”

Another white Union naval officer, Robert S. Critchell, penned an 1864 letter to The New York Times in which he described surveying the bodies of dead Black soldiers along the riverbank in the aftermath. “Most of them had two wounds,” Critchell wrote. “I saw several colored soldiers of the Sixth United States Artillery, with their eyes punched out with bayonets; many of them were shot twice and bayoneted also."

Even one of Forrest’s Confederates painted a scene of the immoral violence, writing that “poor deluded negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down... I with several others tried to stop the butchery, and at one time had partially succeeded but General Forrest ordered them shot down like dogs, and the carnage continued."

A surviving Black combatant, testifying before Congress in 1864, recalled that Forrest’s Confederates “nailed some black sergeants to the logs and set the logs on fire,” and gave a firsthand eyewitness account of seeing Forrest among the violent throngs.

A final report from the House Committee on the Conduct of the War from May 1864 detailed yet more cruelty:

The officers and men seemed to vie with each other in the devilish work; men, women, and even children, wherever found, were deliberately shot down, beaten, and hacked with sabres; some of the children not more than ten years old were forced to stand up and face their murderers while being shot; the sick and the wounded were butchered without mercy, the rebels even entering the hospital building and dragging them out to be shot, or killing them as they lay there unable to offer the least resistance. All over the hillside the work of murder was going on; numbers of our men were collected together in lines or groups and deliberately shot; some were shot while in the river, while others on the bank were shot and their bodies kicked into the water, many of them still living but unable to make any exertions to save themselves from drowning. Some of the rebels stood on the top of the hill or a short distance down its side, and called to our soldiers to come up to them, and as they approached, shot them down in cold blood; if their guns or pistols missed fire, forcing them to stand there until they were again prepared to fire. All around were heard cries of "No quarter!" "No quarter!" "Kill the damned n----ers; shoot them down!" All who asked for mercy were answered by the most cruel taunts and sneers. Some were spared for a time, only to be murdered under circumstances of greater cruelty....

These deeds of murder and cruelty ceased when night came on, only to be renewed the next morning, when the demons carefully sought among the dead lying about in all directions for any of the wounded yet alive, and those they found were deliberately shot. Scores of the dead and wounded were found there the day after the massacre by the men from some of our gunboats who were permitted to go on shore and collect the wounded and bury the dead. The rebels themselves had made a pretence of burying a great many of their victims, but they had merely thrown them, without the least regard to care or decency, into the trenches and ditches about the fort, or the little hollows and ravines on the hill-side, covering them but partially with earth. Portions of heads and faces, hands and feet, were found protruding through the earth in every direction.

And still, there is yet more missing from the Fitch Farms notice about Forrest, whose former property the Fitch family seems so proud to host. Before the war, Forrest made his fortune as a “slave trader.” Samuel Hall, a formerly enslaved man, wrote in 1912 that Forrest “would buy up slaves and keep them in this yard and sell them like people sell hogs today.” Another freedman, Louis Hughes, described how Forrest had cruelly sold off his wife’s relatives.

“When they arrived in Memphis, they were put in the trader’s yard of Nathan Bedford Forrest,” Hughes recounted. “None of [her] family were sold to the same person except my wife and one sister. All the rest were sold to separate persons.”

Forrest likely also raped Black women, both those he enslaved and others, and an 1864 article in the New York Tribune stated as much. Forrest biographer Jack Hurst has a verified record of Forrest’s first act as an enslaver being the “purchase” of “a Negrow [sic] woman named Catharine aged seventeen and her child named Thomas. The Tribune article —“THE BUTCHER FORREST AND HIS FAMILY: All of Them Slave Drivers and Women Whippers”—seems to make reference this same enslaved woman, describing her as Forrest’s extramarital “wife,” a title that cannot be held by someone with no legal autonomy over their body or life. The article also charges Forrest with personally beating a slave to death:

He was accounted mean, vindictive, cruel and unscrupulous. He had two wifes [sic] — one white, the other colored [Catharine], by each of which he had two children. His “patriarchal” wife, Catharine, and his wife, had frequent quarrels or domestic jars. The slave pen of old Bedford Forrest, was a perfect horror to all negroes far and near…

His mode of punishing refractory slaves was to compel four of his fellow slaves to stand and hold the victim stretched out in the air, and then Bedford and his brother John would stand, one on each side, with long, heavy whips, and cut up their victims until the blood trickled to the ground. Women were often stripped naked, and with a bucket of salt water standing by, in which to dip the instruments of torture, a heavy leather thong, their backs were cut up, until the blisters covered the whole surface, the blood of their wounds mingling with the briny mixture to add torment to the infliction. One slave man was whipped to death by Bedford, who used a trace-chain doubled for the purpose of punishment. The slave was secretly buried, and the circumstance was only known to the slaves of the prison, who only dared to refer to the circumstance in whispers.”

Noted historian Eric Foner also writes that a Black freedman named Ned Forrest Hargress was “reputedly the son of a slave woman raped by the Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest as the Civil War drew to a close.” Sydney Nathans’ A Mind to Stay: White Plantation, Black Homeland includes that Forrest and his troops camped overnight in Greensboro, Alabama, in April 1865. An enslaved woman named Dorothy, forced to cook for the Confederates, was later “summoned to the tent of the General.”

“When Dorothy had a son nine months later, on January 1, 1866, she believed that General Nathan Bedford Forrest was his father. She gave her son Forrest’s name to affirm the link.”

All of these crimes, horrors, and violence—sexual and murderous—were committed by the man who owned the log cabin that stands on the Fitch property, and which the Mississippi AG’s father, who died earlier this year at the age of 88, reportedly transported 40 miles, “disassembled and reassembled,” and “lovingly restored” log by log, before moving into it himself. Much of this information is widely known among those of us familiar with Forrest, including “Civil War buff” Bill Fitch and the family he raised on stories from that era. And somehow, the Fitch family continues to brag that it owns this property and invites folks to stay in it, as if to shout their indifference to his murderous anti-Black cruelty—or perhaps to signal their approval of it.

Mississippi Attorney General Fitch was a signatory to a letter that propagates Republican race-baiting and misinformation about critical race theory, and which suggested funding should be denied to public schools that teach “any projects that characterize the United States as irredeemably racist or founded on principles of racism.” Last year, she dropped charges against Canyon Boykin, a white former cop who was indicted by a grand jury in 2016 for manslaughter in the killing of Ricky Ball, a Black 26-year-old, during a traffic stop. She filed an unsuccessful motion in April to put the brakes on a lawsuit by Black Mississippi parents who are suing the state for breaking “federal law by spending less on majority-Black schools than majority-white ones.” Fitch also opposes efforts to overturn an 1890 Jim Crow-era provision in the Mississippi Constitution that bans people who have been charged with felonies from voting for the rest of their lives.

Now she’s attempting to force pregnancies in Mississippi, and ultimately, to end the era of reproductive rights—which fits with the rest of the story, finally told.