Slightly more than halfway through the first Democratic presidential debate on Wednesday night, Sen. Elizabeth Warren was asked if she had a plan to deal with the very real possibility that her domestic agenda would be held up by Republicans in the Senate.

She did, she assured the moderators.

In reality, she didn’t.

“It starts in the White House and it means that everybody we energize in 2020 stays on the frontlines come January 2021,” Warren said. “We have to push from the outside and have leadership from the inside and make this Congress reflect the will of the people.”

For Democrats who lived through the Obama administration, Warren’s response struck a familiar, somewhat stress-inducing note. Twelve years ago, Barack Obama also pledged to use his broad coalition of supporters to keep pressure on Republican lawmakers to pass his agenda. He even built an outside organization to help. The results were suboptimal. Republicans voted in lockstep against his health-care proposal. Just three Senate GOPers backed his stimulus bill. And Mitch McConnell helped lead the GOP back to majority status in Congress by pledging to make Obama a one-term president.

That Warren was now relying on the same script illustrated the main point of tension that has defined the early stages of the Democratic primary. Virtually every candidate running for the Oval Office has an ambitious platform to which he or she can point. But few, if any, have articulated a means for getting that platform into law.

The dynamic was true again during the first night of primary debates. The two-hour affair touched on everything from health-care policy to gun rights, to the detention of children at the border, to the authorization of war in Iran and the existential threat posed by climate change.

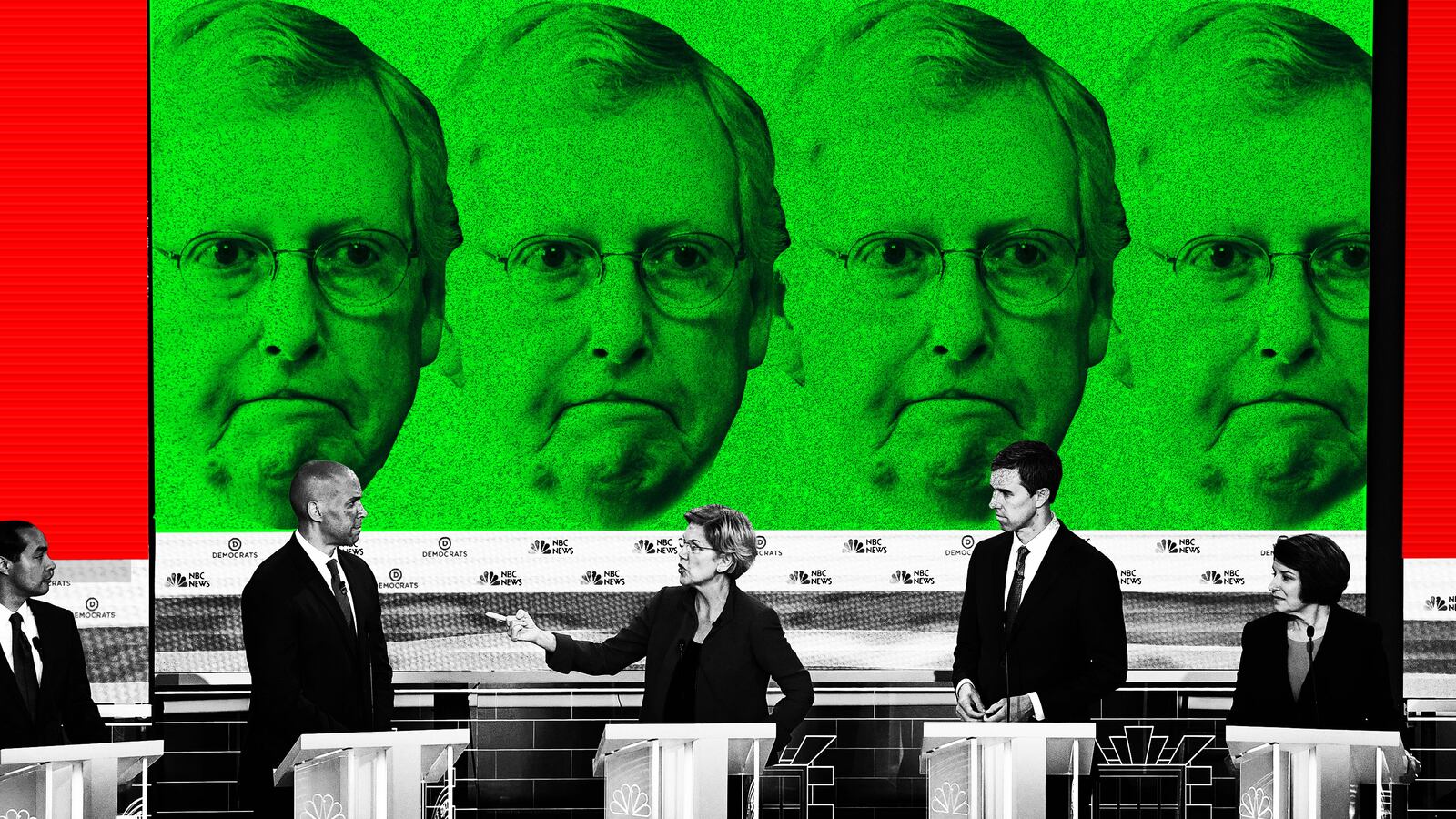

But one person loomed over it all. It wasn’t Donald Trump, the current occupant of the White House, or Joe Biden, the current frontrunner for the nomination. It was McConnell, whose shrewd use of parliamentary procedures and deeply effective hold over his caucus has thwarted Democrats more than anything else.

Indeed, at one point in the evening, the Senate majority leader was the top trending search query on all of Google.

Candidates other than Warren were asked to weigh in on the Kentucky Republican. And their prescriptions for circumventing him were mostly of the same variety. Sen. Cory Booker talked about campaigning in traditionally Republican states like South Carolina and Iowa in order to elect Democratic senators so as to take back the chamber. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio called out Democrats for acting like “the party of elites” and refusing to go into “red states” to “put pressure on their senators.” Former Rep. John Delaney spoke about dialing down the ambition instead of searching for the votes, in hopes of passing legislation with bipartisan majorities. In the spin room after the debate, former HUD Secretary Julian Castro suggested that unseating McConnell itself was the key to the problem.

“There’s no question that he’s an obstacle, but I thought some of the folks that spoke had good points about how we can work on that,” said Castro. “The only way that we can work on that is to go and find a great candidate in Kentucky that can beat him.”

Only Washington Gov. Jay Inslee spoke of eliminating the legislative filibuster to allow bills to pass on a simple majority vote.

But Inslee’s plan would only work if Republicans lose the Senate. And even then, he would need 50 Democratic senators to agree to eliminate the filibuster—a pledge that many current members have resisted.

And so the candidates outlined their proposals under the pretense that they could become law when the reality remains far different.

De Blasio and former Rep. Beto O’Rourke had a contentious exchange early on over whether it was important to maintain some semblance of a private health-care insurance market as part of the party’s broader push to expand Medicare—with little recognition that the votes would not be there to do either. Warren, Booker, and others were pressed about the efficacy of gun buy-back programs and firearm confiscation as a means to reduce gun deaths—without noting that a far-less ambitious proposal to expand background checks didn’t muster 60 votes in the Senate. Sen. Amy Klobuchar tried to pitch better election-security measures, including the need for backup paper ballots—with no one remarking that Republicans in the Senate have blocked such measures these past few weeks.

Not everything that the candidates discussed Wednesday night was doomed to political hopelessness. Some of the proposals could make their way into law without McConnell’s interference, including ideas related to how the federal government interprets immigration law and the regulations surrounding climate policy.

Democratic operatives also argue there is value to candidates pushing bolder ideas now, even if they stand less chance of actual passage. For starters, doing so can help move the window of a debate and help build the support for a proposal over time. It wasn’t too long ago, after all, that even incremental progress on criminal-justice reform and LGBTQ rights seemed dramatically out of reach. On Wednesday night, the main debate around those two topics was around what remained to be done.

But as the night proceeded into its second hour, and the candidates were pressed to talk about how they would handle McConnell should they end up in the Oval, it was not hard to see how their far-reaching agendas would quickly come back to earth.

“Look, these senators, they get a little too cozy with their baronial rules,” Inslee said, after the debate was over. “This is an antiquated, anti-democratic, antebellum thing that stops democracy in this country. And I’m kind of stunned that I’m the only guy who’s been willing to stand up on my hind feet and say that. You cannot have any progressive movement in the Senate until you remove the filibuster from Mitch McConnell.”

With reporting by Gideon Resnick