“Bonjour, Je m’appelle Mitt Romney” may not be the Republican frontrunner’s political death knell—as Newt Gingrich’s supporters in South Carolina hope it would be—but Romney’s 30-month stint as a Mormon missionary in France in the late 1960s came remarkably close to killing him.

The story begins during the U.S. war in Vietnam, when the 19-year-old Romney—who had protested during his year at Stanford in favor of the draft—got a deferment to travel to France in 1966 to seek religious converts to Mormonism. Romney spent much of his time trying to get a population of largely secular Catholics in Bordeaux, Le Havre, and Paris to believe that God chose Joseph Smith to found the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Even then, he wasn’t very successful in convincing people about his deeply held personal beliefs -- he won only two converts in over two years -- a problem that still haunts him in the presidential race today.

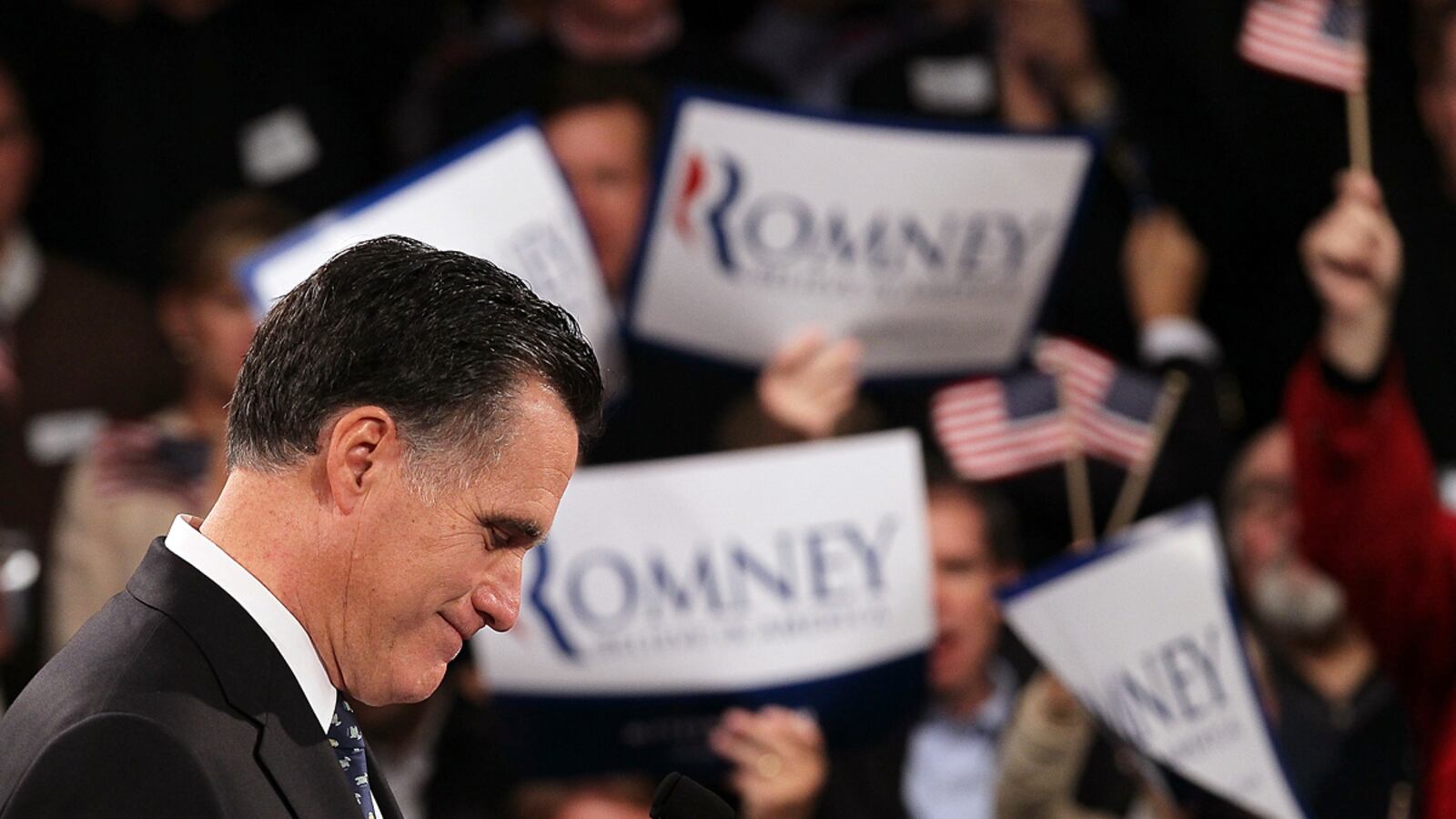

And even then, he displayed the wholesome—some might say goofy—sense of humor, organizational skills, and work ethic that help to explain why Romney was designated an assistant to the American leader of the Mormon mission in France. And that is how, at the age of 21, he ended up behind the steering wheel of a stylish low-riding Citroën DS with the mission leader, his wife, and three others crammed into a car made for five people on a winding road in southwestern France. Another car, driven by a speeding priest, who by most accounts seemed drunk, struck Romney’s car head-on.

Police who arrived on the scene initially assumed that Romney was dead. A photo of him in the hospital later shows him with a cast on his arm and a black eye.) Tragically, the wife of the mission leader did die, and her injured husband departed France almost immediately. Romney, who had been transferred to Paris by then, was temporarily tasked with co-administrating to the needs of 200 missionaries in France until the Mormon hierarchy managed to send a new elder to take the leader’s place.

“When someone who you know dies, everyone is sad—and the Church continues,” Françoise Calmels, a spokesperson for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in France, explained to The Daily Beast. “Missionaries—we have 52,000 in the world—are attacked and killed. It can, and does, happen. And it leaves a mark on them.”

That said, she argues, a tragic experience during a mission should not define the missionary’s entire experience. “You arrive as a young man and you become a man,” Calmels explains. “You live simply, deal with your money, learn a language and talk to people a lot about their problems. It makes you grow, and change. Everyone who has gone on a mission in our Church will tell you that they are the main beneficiaries, because they learn to live. Mitt Romney had this same experience.”

Romney has credited his mission in France with his “growing up” quickly and with solidifying his until-then thin religious dedication. “On a mission, your faith in Jesus Christ either evaporates or it becomes much deeper,” he told The New York Times in 2007. “For me it became much deeper.”

Interestingly, Romney, who as the son of a rich automotive executive-turned-governor and as a businessman who has made hundreds of millions of dollars himself, also emphasized that his spiritual transformation in France came during an unusually failure-ridden period of his life. “Most of what I was trying to do,” he told the Times in 2007, “was rejected.”

Romney has also commented that there were times when he wished that he was fighting in Vietnam, a place where he might have a real impact, rather than stagnating in France. (This also conveniently offers him a rebuttal to those who accuse him of being a chicken-hawk who initially advocated for a war that he didn’t fight in when he could have.) But even in France, Romney somehow missed the real action. In his missionary microcosm, he was hardly immersed in the social revolution of the 1960s that transformed French sexual mores and that spurred impassioned students and workers to man barricades in Paris’ Latin Quarter

Instead, Romney was overseeing creative efforts to bring French people closer to “American night” events and demo baseball games as a tiny first step toward spiritual conversion. And even though he is credited with convincing just two people to convert during his time in France, the numbers, Mrs. Calmels notes, aren’t important. It is also about what the missionary takes away from their experience.

So it is interesting that when Romney has spoken of France on the presidential campaign trail—whether in 2008 or now—it has generally not been to highlight his global experience, but to denigrate France (or, most recently, Europe in general) as a land of decline that has weakened the drive of its citizens with welfare-state comforts. It’s the sort of argument that has changed little since the 1960s, even though Europe’s social safety net has thinned substantially and many European nations have recently embraced stern austerity measures.

“Mitt Romney, for me, is an American, and more importantly, an American politician,” says Calmels. “Even if he wasn’t a member of the Church, I am sure that he would think differently (from the French). He isn’t the only American to think those things. Europeans say bad things about Americans, and Americans say bad things about Europeans.” Especially Americans running for the Republican presidential nomination.

“Even as a Mormon, a French person stays French, an American stays American, and a Swiss stays Swiss,” Calmels explains. “We don’t all just swallow the beliefs of others. During the war in Iraq, the French and the Americans in our church disagreed a lot about that.”

As for the impact of such a prominent politician of Mormon faith, she adds, “This all allows us to speak about the Church, and talk about beliefs, which in a secular country like France isn’t always easy. But we don’t always want Mitt Romney ‘The Mormon’ put on us.”