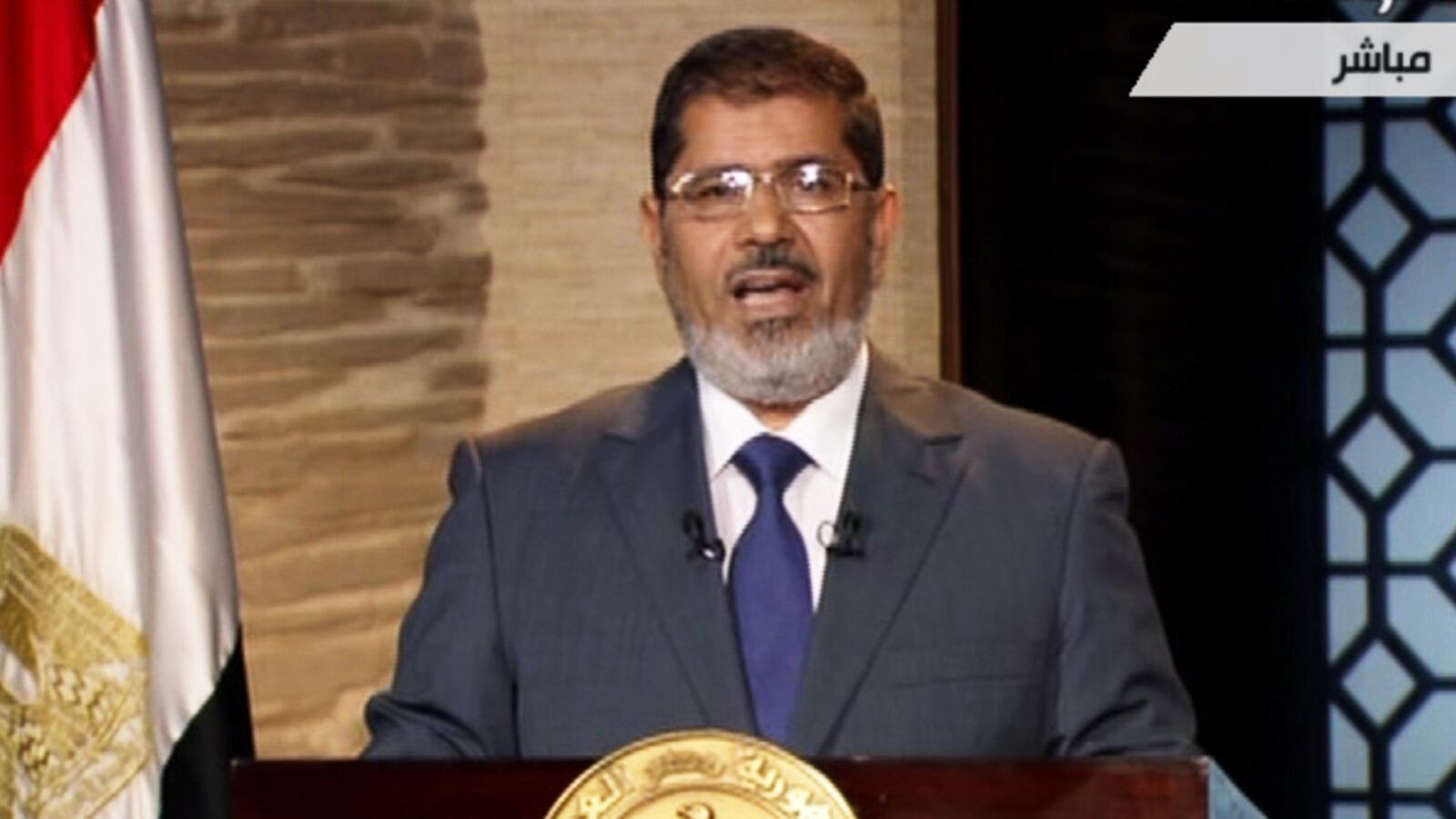

This week, the Presidential Elections Commission, the judicial body that oversaw Egypt’s first relatively free and fair contest for the country’s top job, finally certified Mohamed Morsi Eissa al-Ayat, the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, as the victor. The election had actually concluded a week prior, and while the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) announced its candidate’s triumph almost immediately, the PEC demurred, first saying it would release the result last Thursday, and then postponing until Sunday. Many believed that the delay was that so the judges, and Egypt’s ruling military junta, could figure out a way to cook the numbers to show a Morsi defeat.

This was not the first time that Morsi has had to cool his heels in limbo while a judge would figure out whether (or how) to steal an election from him. I first met Morsi eight years ago, when he was running for reelection to Egypt’s 454-man Parliament. A representative from the Nile delta town of Zagazig, he had been one of 17 Muslim Brotherhood legislators, and had earned a reputation as one of the body’s most vociferous critics of the government of Hosni Mubarak. Perhaps because of this, the word on Morsi’s campaign was that his seat was not safe, and that the regime was intent on removing him from the assembly.

The night of the election, I (and what felt like a thousand Muslim Brothers) stood outside the building in which the votes were being tallied by the judge (in the 2000 and 2005 elections, judicial oversight of vote counting was thought to provide a modicum of integrity to the process). Morsi and his opponent were inside the station, observing the judge do his work. Throughout the evening, we received reports on what was going on inside from a Brother who was in cellphone contact with Morsi or one of his aides. At one point, we began to hear that the numbers were showing a Morsi victory. Shortly afterward, we heard that the judge was now on the phone with superiors in Cairo. Finally, the word came that the judge had been ordered to swap the two candidates’ figures, and Morsi was arguing with him, pleading with him to fear God and do the right thing. The judge, who likely had plenty of more worldly things to fear if he actually took Morsi’s advice, was reportedly apologetic. As he put pen to paper to complete the foul deed, he allegedly turned to Morsi and said, “All I ask is that if you want to curse someone, please just curse me and not my children.”

By the time Morsi emerged from the building, we all knew what had happened, and I remember thinking that the crowd was going to erupt in violence—they were Islamic “fundamentalists” after all. But instead of a call to revenge or mayhem, Morsi gave a short speech in which he recounted regime abuses, celebrated the fact that the Brotherhood had as a whole won more than five times their old number of seats in the assembly, and then asked everyone to go home peacefully. With tears in their eyes, they did. Who could have predicted that a mere seven years later, Morsi would face the same scenario, except this time it would go his way and hand him the presidency?

Morsi assumes Egypt’s highest office at an incredibly dangerous time in the country’s history. The ruling military junta, which had earlier promised to hand over power at the end of June, now seems unlikely to go anywhere. A judicial decision to dissolve Egypt’s Parliament in the days before the presidential election means that legislative authority reverts to the generals, and they can be expected to make their voices heard. Meanwhile, the political landscape remains bitterly divided—not just between supporters of the two presidential candidates, but between young and old, urban and rural, between those who want Islamic law and those who don’t, and between those who want gradual change and those who want radical transformation.

One may legitimately ask, then, whether Morsi is the right man for the job. After all, he wasn’t even the Muslim Brotherhood’s first choice—that honor went to a businessman named Khairat al-Shater, who was disqualified by the PEC due to a Mubarak-era conviction. And the Muslim Brotherhood’s stock has plummeted in recent months. Non-Islamists chided the group—and its allies in Parliament, the more conservative Salafis—for attempting to dominate the constitution-writing process, and for reneging on its earlier promise not to back a consensus candidate for president rather than fielding one of their own.

In his acceptance speech last night, Morsi nodded to the importance of building national unity when he vowed to be the president of all Egyptians. But it’s not even clear that he’s the president of everyone who voted for him. The Brotherhood may be the strongest political force in Egypt, but it’s worth remembering that it did not win the presidency on its own. In the first round of voting, Morsi earned only a quarter of votes cast—around 5.7 million votes. In the runoff, he more than doubled his tally, to 13.2 million. Those extra 7.5 million voters were mainly Egyptians who believed that their revolution would not be worth its name if it discarded Mubarak only to replace him with his protégé. Morsi is the decisive break with the past that many Egyptians have been hoping for. It’s not yet clear whether he also represents a bridge to Egypt’s future.

Fighting the military while restitching Egypt’s tattered political fabric will require a politician of incredible skill, flexibility, and strategic acumen. Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood’s executive committee or “guidance bureau” for the past seven years, has certainly demonstrated his ability to operate within a large organization, but it’s not clear to me that the skills that make one a successful Muslim Brotherhood apparatchik are those that make a successful national leader. Morsi is known for ideological rigidity, and younger Muslim Brothers in Cairo often lament his increasing influence within the organization. But his rigidity was an asset during his time in Parliament, when he was known for standing up on the floor of the assembly and delivering broadsides against the regime. And while many accounts of his parliamentary record focus on the religiously conservative bits of his agenda—it’s true that his first speech on the floor of Parliament was an indictment of interest-based banking, which is forbidden in Islam—he was just as likely to call the government to account for the country’s crumbling infrastructure. One of his proudest achievements as a parliamentarian, in fact, was the building of a flyover that traversed a set of railroad tracks on the way to his district.

But Egypt’s current moment requires something more than a gifted organization man or the faithful representative of a dusty rural electoral district. An inordinate amount of commentary about Morsi in recent weeks has focused on the man’s personality—in particular on his alleged lack of charisma. This focus, I believe, is in part a function of the fact that Morsi’s new job is going to require him to seduce, cajole, and sometimes bully a wide range of political actors. It is true that Morsi is not a typical politician, with none of the glad-handing bonhomie that is characteristic of that species. This is not surprising—he’s a materials engineer and university professor, careers that do not usually attract political animals. He is not a terribly arresting speaker—his acceptance speech included a long and somewhat painful portion where he name checked practically every professional group in Egypt, from diplomats to rickshaw drivers, prompting one wag (OK, it was me) to ask whether he was giving a speech or enumerating a census. And he’s not afraid of alienating people. I once saw him reprimand female worshippers at a mosque in his hometown of Zagazig for chatting too loudly—and this was when he was running for office and presumably needed every vote he could get. But charisma is a relative thing—he may not have it in the absolute sense but compared with the plodding Mubarak, Morsi has it in spades. The question is whether he has enough of it, and enough imagination, creativity, and flexibility, to unite Egyptians for the fight ahead.

Morsi’s opponents are legion. Not only will he have to deal with a power-hungry and paranoid military, he will also have to cope with Egypt’s so-called deep state. After all, Mubarak had almost 30 years, and his predecessors another 30 years before that, to establish a state apparatus that was distinctly inhospitable to the Islamist project. We saw some of this in the clash between the Egyptian judiciary and the MB, as judges (with the blessing of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces) not only disqualified the Brotherhood’s original presidential candidate but also dissolved the first constituent assembly, before putting paid to the Muslim Brotherhood–dominated Parliament. And coping with the judges will be easy compared with the Ministry of the Interior, which was not only the boot of the Mubarak regime on the necks of the Egyptian people, but a body of men with guns whose defining ideology is resistance to the Islamist political project. Morsi has spoken soothing words to the police, but these are not likely to overcome years of indoctrination or change the institution’s raison d'être. Moreover, any concessions Morsi makes to the deep state risk being seen by his allies as a betrayal of the revolution.

Morsi will have his work cut out for him abroad as well. Though it appears that the junta will retain control of foreign affairs and defense portfolios, Morsi can still have a lot of influence in these areas. And for many Americans, who have not followed Egyptian politics closely enough to be able to distinguish among different types of Islamists, it might as well have been Osama bin Laden rather than a bookish university professor who had been elected president. Opponents of Morsi have brought up a 2005 interview that he gave to CNN, in which he rather foolishly questioned the official narrative of 9/11, saying that there “is something fishy” about it. “An airplane or a craft just going through it like a knife in butter?” he asked his interviewer, “I don't see that. Explain it to me.” Though it would of course be preferable if Egypt’s next president were someone who understood what really happened on 9/11 (not least because we still require Egyptian cooperation in fighting terror), there’s a significant difference between someone who denies it happened and someone who thinks it was a good idea. The former is misinformed (or a crank); the latter is the face of modern evil.

Morsi is more Jerry Falwell than Osama Bin Laden. During his 2005 parliamentary campaign, he talked a lot about the United States—remember, this was only two years after the U.S. invasion of Iraq—but more to critique its social model than to rail against its international malfeasance. He lived in Southern California in the late ’70s, so one can imagine that he saw a lot of decadence in his day. On the stump, he would often tell audiences that families in America had so come apart that hospitals were forced to register newborn babies under their mothers’ last names (since, the implication was, rampant promiscuity had rendered the institution of marriage irrelevant).

There was comparatively less America bashing in his presidential campaign—no doubt in part because the crowds were bigger, the number of eyes watching him at home and abroad exponentially greater. But it’s also because Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have grown a lot in the last seven years. We are fond of saying that the Muslim Brotherhood is the most organized political force in Egypt, but this does not mean that they are alone. For several years, liberal and leftist activists have become a force to be reckoned with in Egyptian politics, and to earn their support the Brotherhood has had to compromise. In 2007, when the movement put forth a party platform that rejected the possibility of a female or Christian president, and which proposed a council of religious scholars to advise the Parliament on whether its legislation was sharia-compliant, it came under blistering attack from its would-be allies and, as a result, backtracked. The Brotherhood now declares that only sitting judges have the authority to review laws, and Morsi’s presidential platform says almost nothing about sharia or any of the other traditional themes of political Islam. In fact, the word that appears most frequently in Morsi’s platform is “development.” This doesn’t mean that Morsi won’t try to implement a conservative program, but he’ll be on a very tight leash.

In the coming weeks, we’ll see just how short that leash will be. Morsi—who has just begun settling into Mubarak's old office—is already heading for a fight with the junta by demanding the reinstatement of the Islamist-dominated parliament that was dissolved by court order in early June. Many Muslim Brothers and other revolutionaries have decided to remain in Tahrir Square until their demands are met—which will make it difficult for Morsi to backtrack or compromise with the generals. Whatever happens in the coming days, it appears that Egypt’s new president will have a very short honeymoon indeed.