Billionaire investor Leon Black will step down as chairman of the Museum of Modern Art following protests from prominent artists and concern from fellow trustees over his decades-long friendship and financial ties to sex-trafficker Jeffrey Epstein.

According to The New York Times, the beleaguered private-equity mogul told the executive committee of MoMA’s board that he wasn’t planning to renew his run as chairman once his term expires in July.

The report indicated Black would, however, stay on the board and that trustees worried Black’s departure would risk the museum losing future donations and access to his vast art collection, which includes Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

The announcement comes days after Black quit as CEO of his firm, Apollo Global Management, much earlier than expected. Black has denied any misconduct or involvement in Epstein’s sex ring and said it was a “terrible mistake” to give Epstein a second chance after his 2008 conviction for soliciting a minor girl.

Maria Farmer, who was an art student in New York when Epstein abused her and her underage sister, Annie, in the 1990s, was elated to hear the news of Black’s imminent resignation.

“If you had told me in the 1990s that the art world would begin to extricate itself from Epstein and his associates, I wouldn’t have believed it," she told The Daily Beast. “For so long, I was a lonely voice screaming into the forest. Now people are listening!”

For his part, Black has been adamant that he played no part in Epstein’s crimes.

“Let me be clear,” Black said in October. “There has never been an allegation by anyone that I engaged in any wrongdoing, because I did not. And any suggestion of blackmail or any other connection to Epstein’s reprehensible conduct is categorically untrue.”

In a statement on his separation from Apollo, Black said, “The relentless public attention and media scrutiny concerning my relationship with Jeffrey Epstein—even though the exhaustive Dechert Report concluded there was no evidence of wrongdoing on my part—have taken a toll on my health and have caused me to wish to take some time away from the public spotlight that comes with my daily involvement with this great public company.”

Black apparently wanted to avoid another media firestorm over his MoMA chairmanship, despite claiming he wanted to “pursue my many interests away from Apollo—including the arts, culture, medical research, and philanthropy.” The Times reported Black “did not want to become a distraction to the institution.”

MoMA did not return a request for comment. A representative for Black, Whit Clay, declined to comment.

One MoMA trustee previously told The Daily Beast that members of the board hadn’t been able to share their views on Black’s connections to Epstein, since the museum postponed their meeting twice since February. The full board is expected to meet Tuesday, when Black will likely share his plans to step down.

“There’s people who feel strongly, but there has not been a forum for people to express their thoughts yet,” the person said, adding that they were troubled that MoMA’s chairman had a long-standing relationship with Epstein, who has long been accused of molesting underage girls. “Of course it disturbs me. I have a conscience and I have children.”

As The Daily Beast reported this week, Black was close enough to Epstein to visit the convicted sex-offender’s homes around the world, schedule routine breakfast meetings with him in New York, fund his favorite charities and scientific research, and loan him more than $30 million—only a third of which Epstein ever paid back.

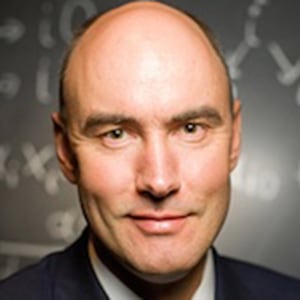

Around 2004, Black also allegedly served as a reference for an employee at Epstein’s Florida mansion: Alfredo Rodriguez, the former butler who snatched Epstein’s infamous “little black book.” One year later, Rodriguez would tell Palm Beach cops what he’d witnessed inside Epstein’s home and that his duties included buying gifts for the young “masseuses” and keeping $2,000 on hand to pay them.

In an audio recording of Rodriguez’s interview with the late police detective Joseph Recarey, Rodriguez claims he landed a job with Epstein thanks to Black. “He gave me a recommendation for Mr. Epstein,” Rodriguez says in the audio file, which was part of a public records collection the Palm Beach state attorney released last year.

It’s unclear whether Rodriguez ever worked for Black, but the former houseman said two of his buddies did. Rodriguez, who worked for Epstein from November 2004 to May 2005, died in December 2014. (In 2010, Rodriguez was arrested by the FBI for attempting to sell Epstein’s address book, which he called the “Holy Grail,” to a victim’s lawyer. He served 18 months in prison.)

When Palm Beach cops began investigating Epstein in 2005, they discovered a trove of phone message pads revealing the names of other wealthy friends: Limited Brands mogul Les Wexner, real estate investor Mort Zuckerman, banking executive Jes Staley, hedge-funder Glenn Dubin, and future president Donald Trump.

The recording indicates police also learned of other powerful connections, including Black.

“I was born in Bolivia, South America, and I have two friends of mine that they were working for Leon Black in New York,” Rodriguez says in the recording, when Recarey asked how he got employed with Epstein. Rodriguez then describes how someone—perhaps Epstein, who in 2003 had accused former butler Juan Alessi of burglary, police records show—hired him because he was seeking a reliable houseman.

“And he said to me … looks like he had a couple of [employees] that stole from him in the past, so he was looking for people like me, he can rely on, because we used to keep a lot of cash in the house. There were guns. Back then I was the only one opening and closing the safe,” Rodriguez says, adding, “I never lost a penny.”

While some of the audio is muffled, Rodriguez can clearly be heard saying: “So I was referred by Leon Black. He gave me a recommendation for Mr. Epstein.” When Recarey asked if Leon Black was related to Epstein’s criminal defense attorney, Roy Black, Rodriguez answered that he ran a “company called Apollo.”

Black’s latest resignation follows months of bad press on his ties to Epstein and the specter of even more protests. A coalition of artists and activists have announced a 10-week “strike” against MoMA for its reliance on billionaire leadership, which includes another former associate of Epstein: hedge-funder Glenn Dubin. (Virginia Giuffre, a survivor of Epstein’s trafficking scheme, claims Epstein and his alleged accomplice Ghislaine Maxwell sent her to powerful men including Dubin, who denies these accusations.)

The coalition, called the International Imagination of Anti-National Anti-Imperialist Feelings, said MoMA trustees realize Black’s “continued presence on the board is a recipe for crisis, but getting rid of him could set a precedent and put at risk MoMA’s use of his priceless art collection. The museum administration is in a classic decision dilemma.”

“Whether Black stays or goes, a consensus has emerged: beyond any one board member, MoMA itself is the problem,” the coalition added, before referring to Dubin and other trustees.

Guerrilla Girls, the anonymous feminist art collective, terminated their book contract with Black’s Phaidon Press in 2019 because of the billionaire’s bond with Epstein. Since then, they’ve also called for Black’s and Dubin’s ousters from MoMA.

In response to the news of Black giving up his chairmanship, Guerrilla Girls said in an email: “Finally!!! But the Guerrilla Girls have questions: Is MoMA keeping the dirty $40 million he donated to them?” The collective was referring to Black and his wife Debra’s donation to MoMA in 2018 in exchange for having a film center named after them.

“Will Black still donate $200 million to survivors of sexual trafficking and abuse, as he offered in an attempt to remain at Apollo and MoMA?” Guerrilla Girls asked.

In January, Black announced he was resigning as Apollo’s CEO after an internal report from the firm revealed he’d paid Epstein $158 million from 2012 to 2017 for estate and tax planning advice—three times more than initially reported.

And last August, Denise N. George, the attorney general for the U.S Virgin Islands, announced she was issuing subpoenas to Black and entities related to him as part of her civil racketeering suit against Epstein’s estate.

Black was pals with Epstein from the mid-1990s until 2018, when the men had a falling out over Epstein’s fees. Epstein had demanded tens of millions of dollars for advising Black on a transaction that saved Black $600 million, the Apollo report alleges.

When Epstein complained about a lack of payment in emails to Black, Epstein “would invoke his friendship with Black” and refer to “personal matters that Black had shared with Epstein in confidence, although there is no evidence that those matters had any relationship to any of Epstein’s criminal activity or to any of Black’s payments to Epstein,” the document claims.

“Throughout Epstein and Black’s relationship, Black viewed Epstein as a friend worthy of his trust,” the report states. “They attended social events together, Black confided in Epstein on personal matters, and Black introduced Epstein to his family. Black regularly visited Epstein’s townhouse in New York to either discuss business or to meet other prominent guests who were visiting Epstein, including well known businessmen, political figures, diplomats, scientists and celebrities. In general, one-on-one breakfast meetings between Black and Epstein would be more common for business meetings, whereas afternoon meetings with other guests would be more common for social visits.”

According to the report, Debra and Leon Black visited Epstein’s New Mexico ranch while en route to California on their private plane. Multiple victims, including Annie Farmer and a woman referred to as Jane Doe 15, say Epstein abused them at this Stanley compound, which is about 40 miles south of Santa Fe.

“At Epstein’s request,” the document says, “Black and his wife provided transportation from Santa Fe to California on Black’s plane to two or more of Epstein’s adult guests in Santa Fe.”