Methods for preventing malaria infections range from the low-tech, like mosquito bed nets and getting rid of standing water; to the uncannily high-tech, like genetically engineering sterile male mosquitoes and introducing them for population control. The World Health Organization approved a vaccine called Mosquirix in October 2021, but the shot is only 30 percent effective at preventing cases of severe malaria.

A new player may soon be entering the field: monoclonal antibodies, a lab-grown treatment that has shown promise for a wide variety of conditions, including cancer and COVID-19. Results from a phase 1 clinical trial published Wednesday in The New England Journal of Medicine indicate that infusions and injections of a monoclonal antibody tailor-made for malaria are safe, and offer hints that the treatment could be highly effective.

“Monoclonal antibodies are an incredibly safe intervention,” study senior author Robert Seder, the Cellular Immunology Section chief at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told The Daily Beast. Unlike other interventions that can depend on a person’s age or ethnic background, “the beauty of the antibody is it should work across all ages, and it's probably not going to be affected by how old you are, or where you live, or what you've experienced.”

ADVERTISEMENT

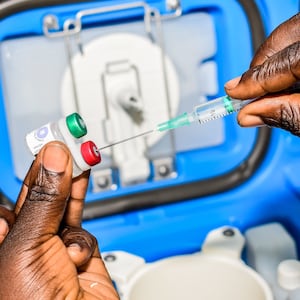

The study recruited 18 American adults to receive a monoclonal antibody at various doses either intravenously or through an injection just under the skin. The antibodies had been engineered to target circumsporozoite proteins (which cover the surface of the malaria parasite upon human infection) and mark the parasite for destruction by the body’s immune system.

Seventeen participants, plus six who had not received the treatment, were then bitten five times each by mosquitoes infected with malaria. Over the next three weeks, all six control participants developed malarial parasites in their blood, but only two of the 17 who received the monoclonal antibody came down with an infection.

Seder said it was not immediately clear why those two participants were infected, since blood work showed that they had the same levels of antibodies as the 15 participants who did not get sick. Nevertheless, the study found that, depending on dosage and form of treatment, the monoclonal antibody prevented infection 80 to 100 percent of the time.

Still, it’s too early to say how much of a game changer this treatment could be—in part because practical constraints could make it difficult to deliver monoclonal antibody treatments to those in need. “The current trial included intravenous administration, which is appropriate in an experimental setting but of questionable use in the field,” malaria researchers Timothy Wells and Cristina Donini wrote in an editorial accompanying the study. The cost of the treatment is another consideration, though current estimates put the antibodies’ price within a similar range as the vaccine.

Additionally, Seder said one-time bite conditions in the lab don’t adequately mimic real-life conditions in countries where malaria is endemic and infected mosquitoes could bite people daily. “That’s why you need the field studies,” he said.

That’s exactly where Seder and his team are headed. They’re getting ready to publish results from a large-scale phase 2 field trial in Mali; another in Kenya is already being planned. Both of these trials focus on children, but the monoclonal antibody might also be given to pregnant women and travelers if the data can back up their safety and efficacy. The field trials will also provide insight into how often people will need shots to keep them protected.

If these studies also bear out encouraging results, Seder said that monoclonal antibody injections could be given to an entire region in combination with antiparasitic drugs and other malaria prevention measures to eradicate the disease.

“Elimination is the aspiration,” he said.