Well at least we know what a peaceful transition of power can actually look like.

Typically, “Biggest Oscar Mistake Ever” is a histrionic label attached to an undeserving winner. For the first time, confusingly, it describes the film that most deserved Best Picture, the film that we needed to see recognized, and whose creators we needed to see rewarded and hear say thank you.

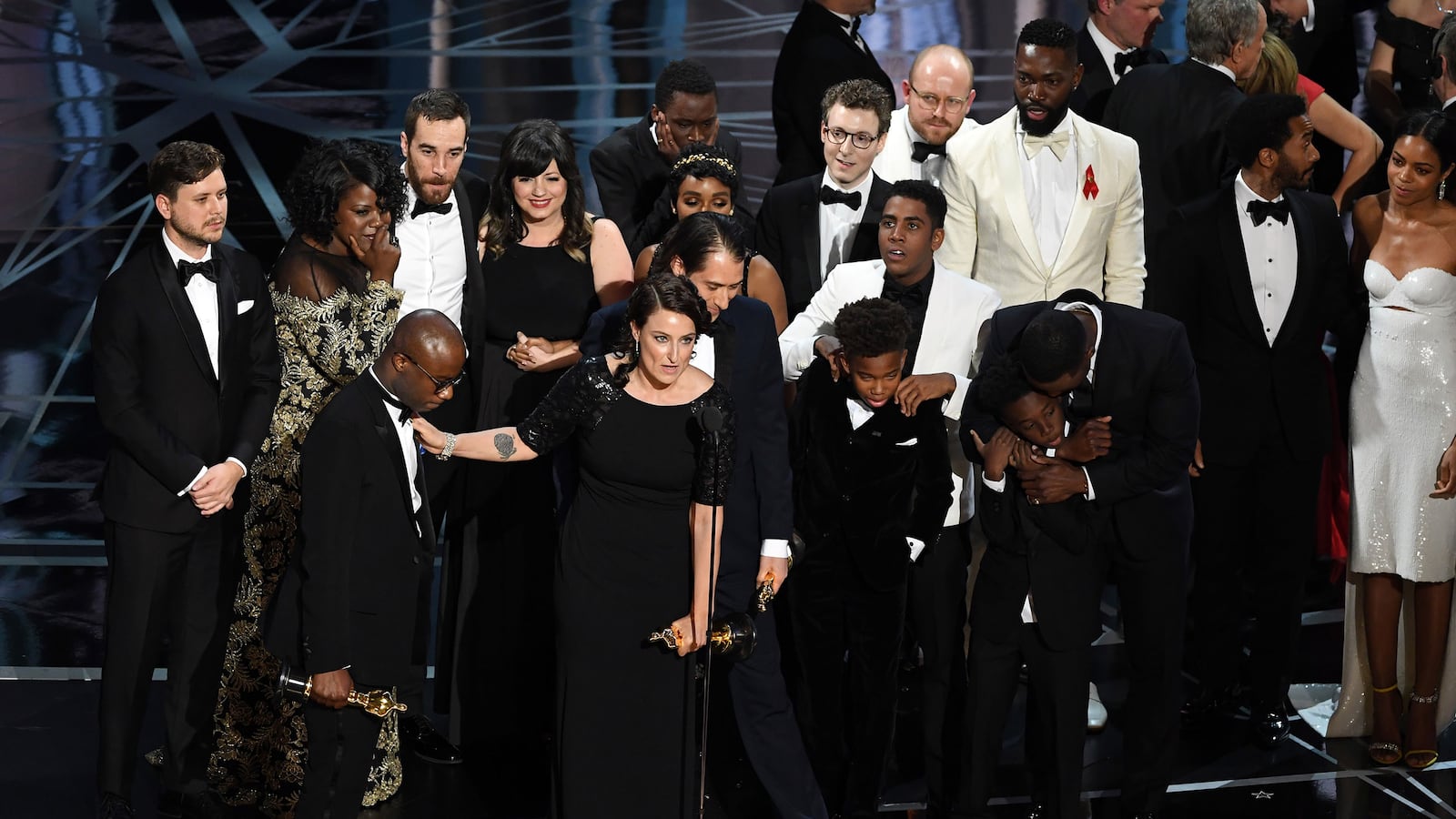

As Warren Beatty flusteredly returned to the stage to explain how he had incorrectly announced La La Land as the winner of Hollywood’s biggest award, ushering the movie musical’s producers off stage as the shell-shocked team from Moonlight incredulously made its way to the microphone, Twitter lit up with its cheeky 2016 election allegories.

“La La Land won the popular vote!” “I guess Moonlight remembered to campaign in Michigan.” You get the gist: all capping off an award season narrative that classified the year’s two most acclaimed films into different factions of a explosive cultural divide.

As the season trudged on, a backlash brewed against La La Land, a charming and enjoyable movie musical with glaring, tone-deaf flaws: the fact that a white man is hailed as the savior of jazz music, rescuing it from a black artist who is tainting it; that it become woefully boring in the middle; that its stars can’t carry a tune; and, worst of all, it didn’t have anything meaningful to say.

From what I could tell, though, the backlash had less to do with the film’s merits than the fact that it was poised to beat Moonlight at the Oscars, maybe one of the few works that actually stands up to the cliché, “a story we need now.”

Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight tells a story in three acts about a black man named Chiron, as he struggles to accept his identity, his sexuality, and his masculinity throughout a life full of barriers—some cultural, some familial, some societal, and some institutional and political.

Perhaps it’s not a surprise that many people will see Moonlight’s big win and Sunday night’s entire political telecast as a rebuke to Trumpism. The speeches were a plea for compassion, and sometimes even a condemnation of the president’s xenophobic policies. The jokes were at Trump’s expense.

And Moonlight’s win over La La Land, with the former literally taking the spoils of its rightful victory out of the latter’s hands, was some sort of revenge fantasy of the underserved, underrepresented, and unspoken for triumphing over the establishment, white privilege, and elitism.

Moonlight is also, as it were, the most qualified “candidate”: the most visually arresting, beautifully written, dynamically acted, artfully shot, meticulously edited, audacious film of the year. Playing against a cultural climate backdropped by racism, homophobia, and hate, it was a haven of serenity to experience this story—and at the same time a forceful blow to the regime behind that turmoil.

The bungled winner announcement will dominate the headlines of the Oscars, but it shouldn’t drown out the most remarkable aspect of the evening as a whole: for this huge, incorrigible, defining mistake, it was one of the few Oscars telecast to, as a whole, “get it right.”

There’s a reason that when Casey Affleck told the crowd while accepting his award for Best Actor for Manchester By the Sea in the face of a tidal wave of scandal and a chorus of social media jeering, “Man, I wish I had something bigger and more meaningful to say,” it seemed so especially sheepish and trite and hollow.

Sunday night’s Oscars—airing as several of its winners boycotted because their countries were part of a travel ban and as civil rights, safety, the arts, and sanity are being stripped away—did have lots of bigger and more meaningful things to say.

Viola Davis said them. Barry Jenkins said them. Gael Garcia Bernal said them. Moonlight said them, and so a film about a little black boy just won the first Best Picture in Trump’s America.

And they all said them amid a healthy amount of laughs courtesy of host Jimmy Kimmel, who, in a thankless emcee role, did a respectable job balancing Hollywood humor, anti-Trump humor, and, yes, seriousness for most of the night.

The Oscars telecast wasn’t perfect, because it never is. For the love of god they gave Best Picture to the wrong film first—maybe one of the best live TV moments in history, but certainly not perfect.

But, yes, it had something bigger and meaningful to say. It’s always had the power to say it. Finally, it wasn’t just the artists but, with this Moonlight win, the institution—the film industry, the Academy, Hollywood—that said it.

It began with the ribbons, light blue worn on lapels and dresses in support of the ACLU, the first sign that this year’s Oscars wouldn’t have the “how political?” question hanging over it, but instead treat it as a mandate.

Introducing politics into the ceremony, an inevitability given how much it has infiltrated, to mixed results, awards ceremonies this year so far, was as awkward as it always is.

The night started with a dance party, as Justin Timberlake sang “Can’t Stop the Feeling”—just to take care of sending award-show Twitter into a collective rage quick and early. Nothing says “I’m a cool guy!” like complaining about this harmless song. Me? I thought it was a fun way to start the show.

Maybe everybody just needs to dance.

These people have been campaigning for these damn trophies for roughly 300 years by this point. Matt Damon wakes up in the middle reciting the story about how he was supposed to star in Manchester By the Sea and Casey Affleck was the only person he’d let play the part instead. It’s been a hard 2017. They needed to have fun! All of Hollywood was in the aisles, clapping their hands together, getting that feeling in their bodies, and for four minutes they acted as if the world outside wasn’t horrible.

Even Isabelle Huppert was there bopping her head behind Kurt Russell.

It wasn’t a grand political statement to start the night off with. But short of the 20 acting nominees joining arms in front of a burning flag while Lin-Manuel Miranda tap dances across stage wearing a melting Donald Trump mask, it was kind of the only way to begin the proceedings: with spectacle and joy, and letting the art and the artists later speak for themselves.

Host Jimmy Kimmel seemed to understand that, too.

His opening monologue was hammy, with requisite shots at Donald Trump, but self-effacing enough to not seem like the liberal Hollywood elites were gathered for an annual circle jerk.

He landed some great jokes: “I want to say thank you to President Trump. I mean, remember last year when it seemed like the Oscars were racist?” This was a year in film, he said, in which “black people saved NASA and white people saved jazz. That’s what you call progress.”

And when he went directly for Trump, he succeeded wildly, whether it was leading the entire auditorium in a standing ovation for “overrated” Meryl Streep or baiting him with tweets.

But he, too, left the bigger, more meaningful things to the talent to say.

Moonlight’s Mahershala Ali, a Muslim, took home the first Oscar of the night. Later, Barry Jenkins and Tarell Alvin McCraney won Best Adapted Screenplay.

“For all you people out there who feel like there’s no mirror for you, that your life is not reflected, the Academy has your back,” Jenkins said. “The ACLU has your back. We have your back. And for the next four years we won’t leave you alone. We will not forget you.”

Then McCraney echoed: “This goes out to all those black and brown boys and girls and non gender conforming who don’t see themselves. We’re trying to show you you and us.” “

Presenting Best Animated Feature, Gael Garcia Bernal said, "As a Mexican, as a human being, I am against any wall that wants to separate us." And the man he presented the award to, Zootopia co-director Rich Howard went further: “We are so grateful to the audiences all over the world that embraced this film with this story of tolerance being more powerful than fear of the other.”

Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi sent a statement in abstentia when he won for Best Foreign Language Film for The Salesman: "I'm sorry I'm not with you tonight. My absence is out of respect for the people of my country and those from other six nations who have been disrespected by the inhumane law that bans entry of immigrants to the U.S. Dividing the world into the U.S. and our enemies categories creates fear—a deceitful justification for aggression and war."

But beyond what people said, it was what audiences were able to see.

We saw Taraji P. Henson, Janelle Monae, and Octavia Spencer standing together as three fiercely talented black movie stars standing in their power as the leads of Hidden Figures, the highest-grossing Best Picture nominee. Then they used that moment to invite on stage Katherine Johnson, giving visibility to a real-life hero whose story demanded to be told, but for so long wasn’t.

Sixteen-year-old Auli’i Cravalho, a Hawaiian teenager of Filipino, Chinese, Irish, Native Hawaiian, Portuguese, and Puerto Rican descent, sang a song with Lin-Manuel Miranda from Moana, and girls and boys who look like them got to see that. They get to dream that.

In her extraordinary speech for Best Supporting Actress, Fences star Viola Davis thanked playwright August Wilson, “who exhumed and exalted the ordinary people.” Rose in Fences. Juan in Moonlight. These are ordinary people whose stories aren’t often told. And now they’ve not just been shared, they’ve been celebrated.

Today, we need those stories shared. We need them celebrated. And while it’s tempting to roll your eyes at an awards show for having an air of importance, look beneath the night’s self-congratulation for an earnest message about how storytelling has the power to change society, and change lives.

Even the producer for La La Land, when he thought he was winning Best Picture, adhered to that message when giving his now-nullified acceptance speech: “There’s a lot of love in this room. And let’s use it to create and champion bold and diverse work, work that inspires us towards joy, towards hope, and towards empathy.”

No film accomplishes that like Moonlight. That it won Sunday night is no mistake. It’s justice, at a time when that seems impossible. Of course, that’s the power of cinema: making you believe in the impossible.