It’s crept in slowly: longtime New York establishments have slowly shuttered their doors, replaced by unobtainable high-rise condos, trendy shops with $100 tee shirts, and the feeling that everything you once knew no longer exists. The neighborhoods are changing and taking history with it.

Landmarks like Studio 54 and CBGB came and went. Bleecker Bob’s Record Store closed after four vibrant decades. And De Robertis pastry shop in the East Village ended its 114-year run earlier this year. The Lower East Side’s Streit’s Matzo Factory, which opened for business a century ago, is just the latest victim.

However, Moscot, an eyewear brand so synonymous with the City that its frames are recognized all across the globe, seems to be a last-man-standing in a rapidly changing metropolis—and even they were booted from their store at 118 Orchard Street to make way for new developments.

“We were determined not to leave,” Dr. Harvey Moscot, the fourth generation heir to the business told The Daily Beast while discussing the brand’s centennial anniversary. “We were born on Orchard Street and we will die on Orchard Street.” Luckily, they secured a 20-year-lease just across the street (at 108 Orchard Street), protecting them from the drastic rent hikes that have forced other family-run institutions across the downtown area out of business or out of Manhattan.

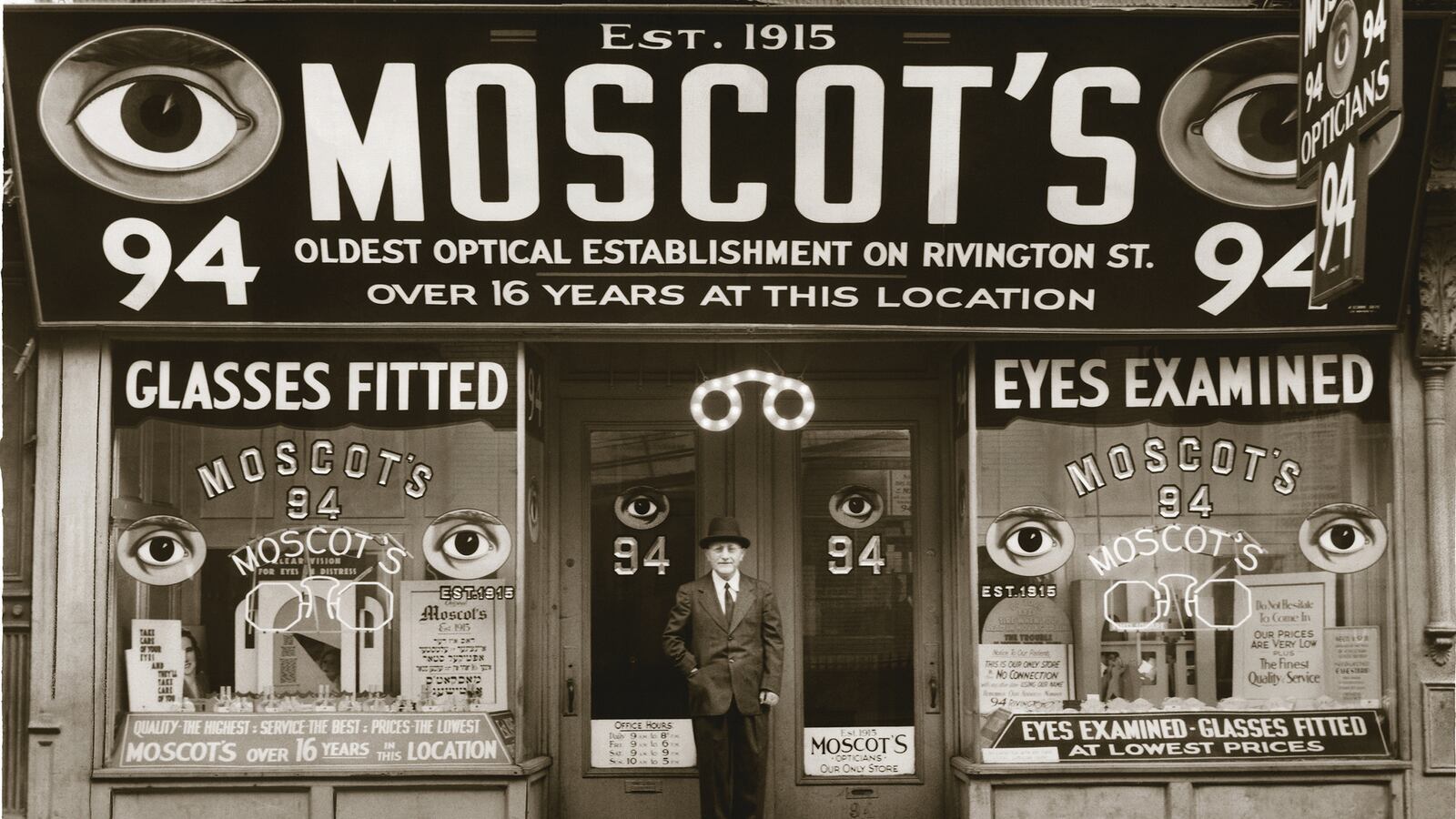

Moscot’s history is rich, and moving. In 1915, fresh from Eastern Europe, Hyman Moscot began selling cheap, ready-made eyeglasses from his pushcart on Orchard Street. Serving the many immigrants that poured into the Lower East Side, he spoke little English but had a knack for optometry and was dead set on living the American dream.

Soon, the pushcart went stationary. Hyman opened his first retail store on nearby Rivington Street and his 15-year-old son, Sol, took over. He moved the business to its Orchard Street outpost, where it sat for almost eight decades.

The mustard-yellow sign with giant, black-rimed glasses that adorned its storefront became synonymous with the neighborhood and downtown New York.

But much has changed since the early days of the twentieth century. Eyewear has transformed into a fashion accessory, becoming as shoppable as next season’s “it” bag or a must-have winter coat. And with that came competition.

Conglomerates like Luxotica, which was formed in 1961, took over the market. They design and sell over 80% of the world’s major eyewear brands, including Ray-Ban, Persol, Prada and Miu Miu.

Luxury brand Oliver People’s opened in 1986. And start-up favorite Warby Parker began offering stylish frames (and lenses) at extremely affordable prices only five years ago. They’ve rapidly become a quick-and-easy staple amongst both the masses and the fashion savvy.

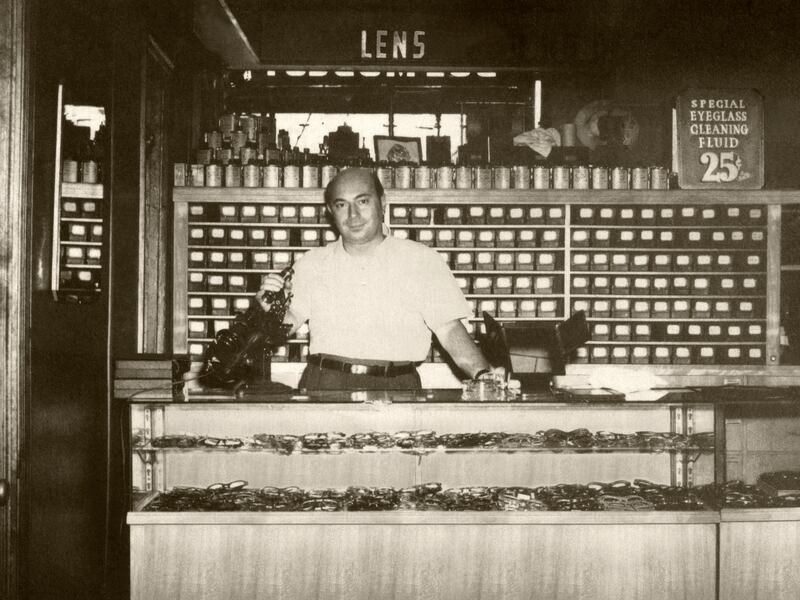

So what sets the mom-and-pop style of Moscot apart from its millennial rivals? Its familial customer service, for one. “Sol was very personal, as was the customer service,” Harvey said. “He would write personalized thank you letters to customers who referred others, discounts perhaps, and during World War II, he gave away free eyewear. We try to keep the same level of exemplary customer service that we have for the past 80 years.”

Today, the family still recognizes its customers, making sure employees carry on with the utmost respect to Sol’s traditions. Harvey even founded Moscot Mobileyes in 2008, which gives free eye exams and frames to underprivileged kids and victims of abuse. Their next big outing is to a new charity that houses sexually trafficked women.

Competitive brands have only recently incorporated a do-gooder attitude within their manifestos. Moscot was founded upon it one-hundred-years ago.

They also keep everything in-house. Wendy Simmons, the brand’s co-president, acts as concept designer and photographer for all of their campaigns. They don’t pay for advertising and produce all marketing materials themselves, just as former generations once did.

As for the product, the designers constantly return to archived classics when looking for the next season’s inspiration.

“The shape has always been really important,” Zack Moscot, Harvey’s son and product designer, said. “People recognize a Moscot frame by its shape, so we are trying to create that identity with new frames, based on what we’ve always done.”

The frame’s vintage appeal keeps it consistently cool and contemporary when collaborating with fashion favorites like BLK DNM and Ace Hotel as well as musicians Myles Kennedy and The Roots—because music runs deep within their veins.

Harvey, an avid guitarist, haphazardly spawned Moscot Music during a quiet, rainy day. A friend stopped in and they began performing, which spawned the idea for a once-a-month concert for the public.

Now, the company hosts up-and-coming bands such as Bret Dennen, Young Guns, Little Daylight and award winners Matt & Kim, who were patients of Harvey’s for years. It’s a bit of a throwback to iconic venues from the neighborhood that no longer exist—like CBGB, which gave a start to greats like Patti Smith, Blondie, The Ramones, B-52s, and Talking Heads.

Gearing up for celebrations over the next year, Moscot has limited edition frames, special memorabilia, and a few monumental fundraisers and concerts planned for commemoration.

But, in the midst of celebrating the past, the Moscot family has kept a beady eye on the future. Having already expanded twice in New York—a flagship store in Greenwich Village and an outpost in Brooklyn—the brand saw its first overseas expansion last year. The location: an up-and-coming neighborhood in Seoul, much like the Lower East Side once was.

“The following and the loyalty there is very high,” Harvey said of the partnership with their Korean distributors. “And they really appreciated our New York story. They understood our brand and understood our values and we are confident that they can replicate them in their culture.”

And, with its new Orchard Street home secured, they are ready to take on the rest of the world.