“Be not afraid of greatness. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and others have greatness thrust upon them.” —William Shakespeare

Muhammad Ali was to sports what William Shakespeare was to language.

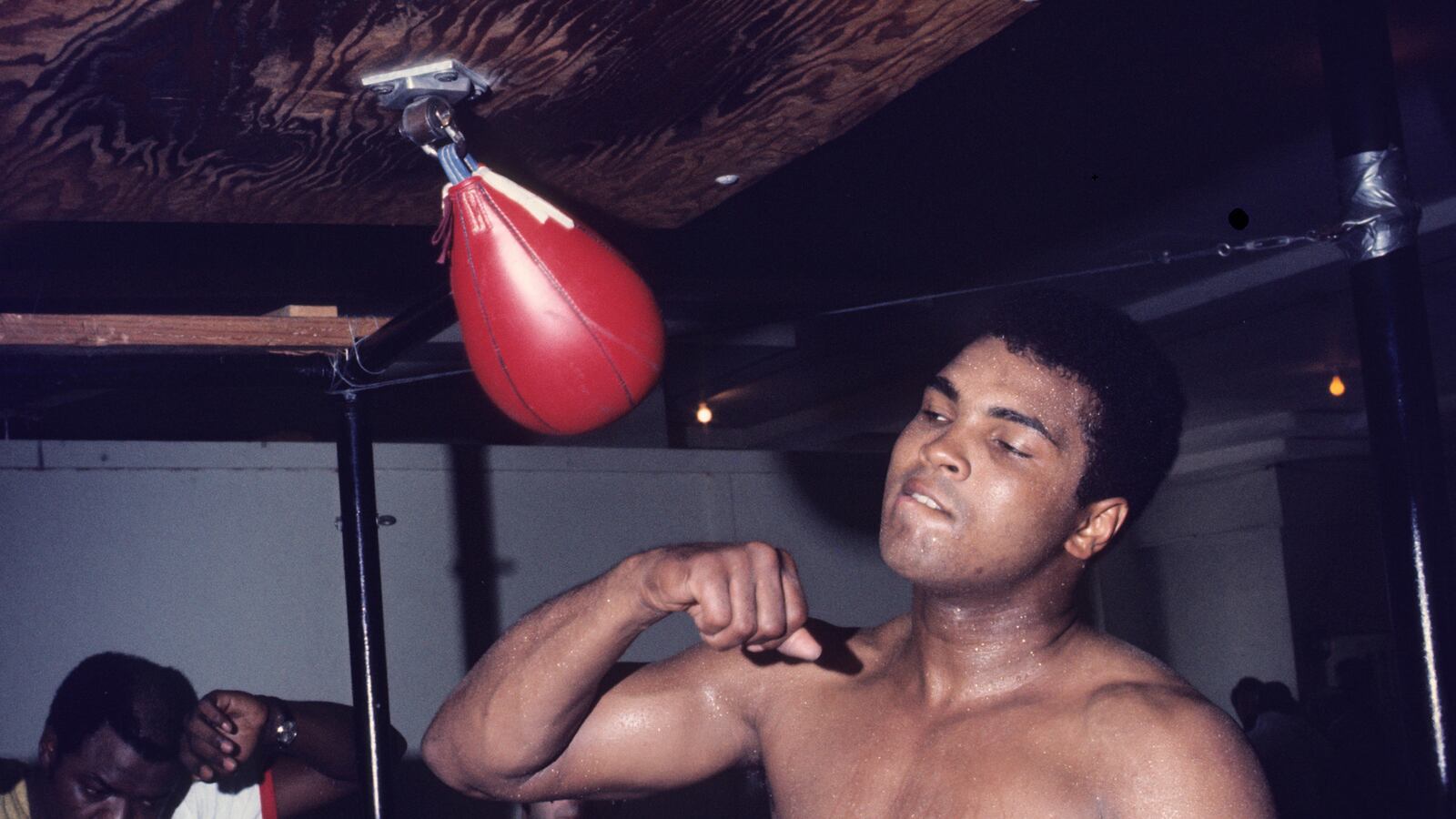

During the peak of his unforgettable career and controversial stands against America’s status quo, he risked death and grievous bodily harm to earn the world’s most recognizable face. Still more than his transcendent achievements in the ring, the mind, spirit, and heart that lay behind that face incited a revolution in the consciousness of his time.

He had more than any fighter before or since, but he gave far more. After a professional career that spanned 21 years in the ring—61 fights, 548 rounds, over a full grueling day fighting under the lights before audiences the world over—Ali’s spirit and generosity as a global citizen surpassed his legacy as an athlete.

Emerging from an era where too many snipers’ bullets stole too many heroic characters from American life, it was rumored that Ali’s face too was once gazed from such a malevolent scope. Fortunately, so the rumor goes, in that instant Ali smiled. Not even his hired assassin had it in him to pull the trigger to take it away from us.

Ali, who’s death was announced just after midnight on Saturday, after he was hospitalized Thursday with a respiratory condition that rapidly deteriorated, was born Cassius Marcellus Clay in Louisville, Kentucky on Jan. 17, 1942. Twelve years later, a local Louisville thief snatched Clay’s bicycle. The hopping-mad boy stumbled upon a neighborhood cop and boxing coach named Joe E. Martin and was encouraged to visit a gym so he could learn how to whup the thief. It was there the skinny kid with fast hands developed into a fighter capable of winning six Kentucky Golden Gloves and two national titles before moving on to the Olympic games in Rome in 1960. He returned home to Louisville a light-heavyweight Olympic champion with a gold medal around his neck, yet Clay still couldn’t receive service at restaurants in his hometown.

Leaving behind an amateur record of 100 wins and only five losses, he turned professional in late 1960. For the next three years—leading up to his iconic championship fight with Sonny Liston—Clay defeated every opponent put in front of him, racking up a pristine record of 19-0. However, Clay’s rise into the heavyweight ranks as a contender betrayed glimpses to many he was nothing more than hype. He was dropped twice on his way to Liston and the bell saved him on one occasion from near-certain defeat. Clay’s braggadocio style and contempt for opponents earned more cheers from crowds when Henry Cooper and Sonny Banks knocked him to the canvass than in his victories. Even before Clay changed his name and joined the Nation of Islam, much of white America despised him, and expected the menacing heavyweight champion and ex-convict Sonny Liston to put the Louisville Lip in his place. They favored Liston by 7-1 odds to do so.

When the fight took place in Miami Beach in early 1964, the Beatles had just invaded America on Ed Sullivan. President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated the previous November. With the Vietnam War about to escalate to horrific proportions with the Gulf of Tonkin, Americans, watching their world being turned upside down, turned their eyes to Liston and Clay fighting for the greatest championship in sports. Many critics had doubted Clay would even show up for the fight. And then they watched Clay take a shocking early lead until something went mysteriously wrong. At the end of the fourth round, Clay’s eyes burning in blinding agony, the odds makers were nearly proved right in prophesizing his demise. He asked his trainer Angelo Dundee to cut off his gloves and call the fight. Dundee refused and shoved him back into the center of the ring with one instruction: “Run!” By the seventh round, Liston refused to answer the bell and, at 22, Cassius Clay was champion of the world, nearly falling out of the ring as he screamed into press row: “Eat your words! Eat your words!” Moments later an interviewer pushed a microphone before his face and he roared, “I shook up the world! I shook up the world! I must be the greatest!” The era had just scratched the surface of its defining champion and symbol.

The following year, in 1965, just before his rematch with Sonny Liston, Cassius Clay converted to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. Ali would knock out Liston in their rematch inside of a round in one of the most controversial fights in heavyweight history. He went on to defend his title several more times until, in February of 1966, the Louisville draft board reclassified his draft status. In defiance, Ali countered with the infamous statement to the media, “I ain’t got nothing against no Viet Cong. No Viet Cong never called me nigger.”

Ali was in the prime of his career and height of his earning power drawing record-breaking crowds against the likes of Cleveland Williams and Ernie Terrell. After his March 22, 1967 knockout victory over Zora Foley, Ali was stripped of his title for refusing to be drafted into a Vietnam War that had already killed nearly 30,000 Americans. After his boxing license was suspended, he was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in prison on June 20, 1967.

Ali was broke and unable to earn a living in his chosen profession for the next three years while he appealed the verdict. While in exile, Ali spoke out at college campuses across the United States. After Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated and opposition to the Vietnam War intensified, finally Ali was granted a boxing license and resumed his career in the summer of 1970 against a rugged contender, Jerry Quarry. Ali then won in federal court and the boxing commission of New York had no choice but to reinstate him, which paved the way for a showdown with the former Olympic Champion and undefeated, newly crowned world champion Joe Frazier, in what was billed as the “Fight of the Century.”

On March 8, 1971, in arguably the most anticipated event in sports history, a contest simply billed as “The Fight” distilled and divided America down racial, political, and religious lines. Ali and Frazier were each guaranteed an unprecedented $2.5 million, the highest sum given to any athlete or entertainer up to that time. Fifty countries purchased the television rights and the fight was broadcast in dozens of languages with an estimated audience of 300 million. More Americans tuned in to watch Ali-Frazier than had watched a human being set foot on the moon two years earlier.

On fight night, Madison Square Garden had more stars than the Oscars and Grammys combined, along with all the underworld’s top brass. The lights dimmed and both champions came to the center of the ring to begin 15 grueling rounds under the lights. Frazier would land an iconic blow in the 14th round that would drop Ali, but where nearly all of Frazier’s opponents would be flattened, Ali miraculously rose at the count of three to continue until the final bell of the 15th round. It was said during Babe Ruth’s era in baseball that the second most exciting moment after a Ruth homerun was Ruth striking out. After his first professional loss, Muhammad Ali proved to be even more compelling in defeat than he had previously been in victory.

Ali fought 13 more times until avenging his loss to Frazier in 1974, setting the stage for a title shot against undefeated, brooding heavyweight champion George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire. “The Rumble in the Jungle” introduced the world to Don King. Ali introduced the “rope-a-dope” to 60,000 in attendance and hundreds of millions world wide, again defying the odds and electrifying the sporting world by regaining the heavyweight crown at age 32.

Muhammad Ali fought 14 fights over the next seven years in increasing decline. Most experts agree he spent much of his life outside the ring paying the toll of the savage brutality endured during that stretch. The final fight in his epic trilogy against Joe Frazier in Manilla brought Ali to death’s doorstep. From there he lost the heavyweight championship and then regained it an unprecedented third time in defeating Leon Spinks, but by 1980, still unwilling to walk away from boxing despite numerous pleas from the sporting world, came a sad end to a majestic career against the likes of Larry Holmes and finally Trevor Berbick.

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s syndrome in 1984 but maintained a highly active and successful role as an international ambassador for peace. He brought millions of dollars of humanitarian aid to Cuba, negotiated for hostages during the Gulf War, and in 1996, lit the flame at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. In 2002, he went to Afghanistan as the UN Messenger of peace and embarked on numerous goodwill tours internationally. His health was in severe decline by 2013, struggling with the symptoms of Parkinson’s to such an extent he could barely speak.

Separated by nearly four decades from his momentous achievements inside of the ring during his sublime career, Muhammad Ali’s face may no longer be the most famous on earth. Attention spans are short these days. But for everything he stood for inside and outside of the ring, his face will be remembered as one of the world’s most beloved.