The City of London, aka the Square Mile—as designated on street signs and addresses by the EC1 postal code—is among the world’s preeminent economic epicenters, where immense wealth flows in and out from around the globe. But remove a single letter from that address, to just E1, which is literally across the street, and you find yourself instead in the East End among the poorest of the poor. Here money hasn’t trickled downstream, sideways, or anywhere near it. The line between wealth and poverty is so clearly delineated that you can stand with one foot in wealth and the other in poverty at the same time.

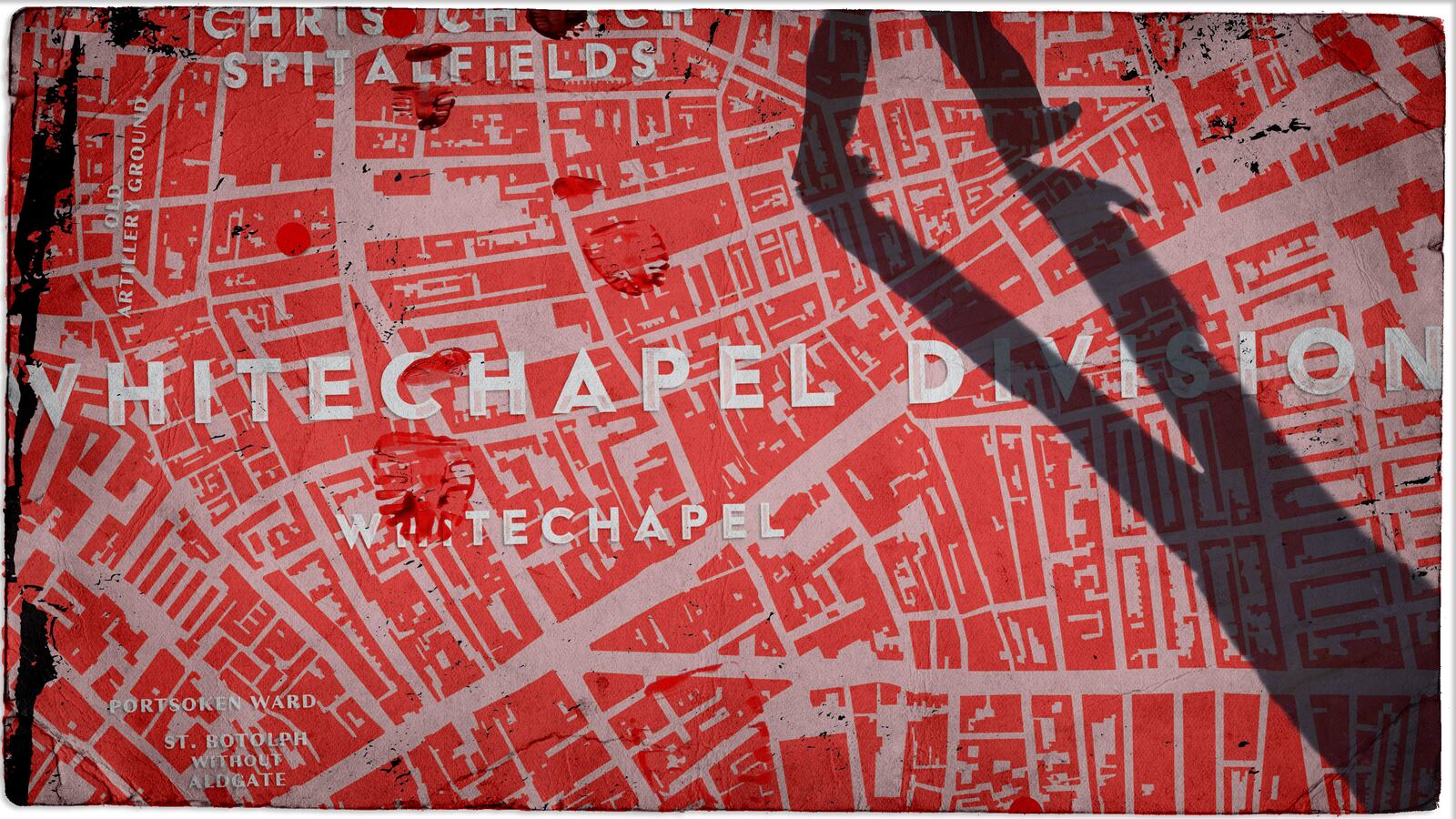

Whitechapel within London’s East End is the notoriously grim district known for a series of murders that took place between Aug. 31 and Nov. 9, 1888, a small window ever after called the “Autumn of Terror.” Jack the Ripper, as the epochal killer came to be known, murdered and mutilated the bodies of five prostitutes by asphyxiating them, slitting their throats, and disfiguring their corpses in such grotesque fashion that this sequence of murders continues to intrigue generations of Ripperologists.

It is here, on an unseasonably chilly evening near Spitalfields Market within the Whitechapel district, that a disparate bunch of tourists and I find Johnny, a lifelong Ripperologist and, as we will shortly discover, our impressively enthusiastic guide for “The Jack the Ripper Tour, brought to you by Ripper-Vision ™.”

Ripper-Vision ™ is the tour to take, but it must be done at night, not only for creep factor but because the eponymous part, Ripper-Vision ™ itself, is a handheld slide projector a smidge larger than a cell phone, a simple but effective means of projecting architectural overlays, autopsy photos, and crime scenes onto walls where the crimes took place. “If a building is no longer there, no worries, we’ll simply put it right back in so you can see it,” the website reads.

Below the belt, Johnny’s just another punk kid in blue jeans. From top hat to waistcoat, though, he’s all ruffles, brass buttons, velvet, and tails. He removes his hat to greet us and smooths his long, greasy hair. Better still, to convince us further of his worth, he shows us a gaudy, tabloid sketch of a fiendish Ripper with a bloody skeleton face. Then, he slowly pulls back his sleeve as a visual punchline: “I mean, that is such an iconic image that your bloody tour guide got it tattooed on his arm.”

In the last half of the 19th century, England was inundated with immigrants. Within a single decade, 50,000 Jews fled to Great Britain from Germany, Poland, and Russia to escape persecution. Roughly a million Irish emigrated to avoid starvation during the Potato Famine. Many wound up in the East End.

“The East End of London,” Johnny says, “has only got a modicum better than it was 130 years ago.” In 1888, 76,000 people lived in less than a square mile in Whitechapel, most of them struggling for the meagerest food and shelter. It was a place to blend in, get lost, disappear.

Honest jobs at the docks or as carters—the men who moved stuff with a horse cart—didn’t pay a lot. Women worked as charwomen (domestic workers) and seamstresses. So otherwise honest people resorted to crime. To make ends meet, children took a page out of Oliver Twist to pick a pocket or two. Men were bullyboys—or pimps—luring customers to private quarters where prostitutes then robbed them at knifepoint while their pants were off. There were an estimated 1,200 “working women,” ranging between the ages of 12 and 60, who ventured inside the perilous maze of Whitechapel, seeking customers for a “four-penny knee trembler,” as Johnny calls it.

“Four old pence for their sorry wares,” he says, pointing out that it was no coincidence that the price of a trick was also the going rate for a night’s sleep in one of the area’s 233 loosely regulated common lodging houses, or “doss” houses, as they were known. There coffin-sized mattresses of urine-soaked, rodent-infested straw and rags were lined up on the floor with separate areas for men, women or married couples. The doss house deputies didn’t check for proof of marriage, and the marital beds were used to turn tricks as well.

Pinpointing the moment when Jack the Ripper began his bloody extracurriculars is anyone’s guess. Murder wasn’t unusual. Disemboweling women was. And, a few of his ascribed murders didn’t exactly follow the Ripper’s MO with respect to the grave injuries he inflicted on the agreed-upon “Canonical Five” victims. But it didn’t deviate entirely.

Our first stop on the Ripper-Vision tour is the entryway of George Yard Buildings, where Martha Tabram’s corpse was found on a stairwell landing in the early morning of Aug. 7, 1888. Her death occurred shortly before the main Ripper spree began, and so while she may have been one of Jack’s early victims, she is not numbered among the “Canonical Five.”

“George Yard Buildings were home to many of the working class poor back in 1888. But it’s also where many ladies would take their customers for a little bit of discretion,” Johnny explains. The buildings came down long ago, but the remaining Victorian brick facades comprise almost an entire city block on Gunthorpe Street, which is dark, narrow, and full of hollows. We pass a still beautiful building that sheltered homeless women in 1888 to reach the spot where Tabram took her final breath.

Martha Tabram

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Public DomainShe was last seen accompanied by a soldier. “She was known to service the servicemen—you know what I mean by that. She went to the dark stairwell with this guy, and that’s the last she is seen alive—at midnight,” Johnny says, pointing to the spot where she was discovered about five hours later on the first-floor landing.

A lot of blood at a crime scene was not Ripper’s style. But cutting the throat, stomach, sexual organs, and abdomen was. Tabram sustained 39 stab wounds to areas that the Ripper mutilated far more skillfully on his later victims. Tabram’s was a particularly bloody end, and the wound to her chest appeared to have been inflicted by a bayonet—a soldier’s weapon. But, as with later murders, no one heard a thing. There were no witnesses, other than her friend Mary Ann Connolly, who had also nabbed a paying customer at the time Tabram took her client. Connolly, however, was so drunk that she couldn’t provide a credible explanation or identification.

A serviceman was suspected, but as sex workers were third-class citizens, and crime was so prevalent, there wasn’t much investigation. She had left the pub with a soldier and a soldier was seen loitering in the area where Martha’s body was found, so the culprit was likely a soldier, QED. But was it the serial murderer soon to be known as Jack the Ripper?

“It’s worth pointing out,” Johnny says. “Martha Tabram was just 39 years old.” “That sure is a rough 39,” an American woman on the tour replies unkindly. Ironically, she herself kind of resembles Martha’s morgue photo that Johnny has pulled from a spiral-bound binder, only alive and hopefully way older than 39. It’s not yet dark enough to emblazon Martha’s coroner’s shot onto the wall. So, for a few more crime scenes, we have to make do with the photobook.

In 1888, residents imbibed cheap alcohol, bathtub gin so strong it could eat through paint and iron. The country’s own version of Prohibition having passed, over-consumption was endemic, women and men alike aged rapidly as they remained drunk to battle despair and the bleak reality of living hand-to-mouth in the human and industrial waste that prevailing westerly winds blew down the Thames into the East End.

On Aug. 31, a few weeks after Martha Tabram’s murder, Mary Ann “Polly” Nicholls was turned away from the lodging house after drinking away the last of her money at Ye Frying Pan pub. On her way out, she confidently turned to the barman and said, “Never mind. I’ll soon get my doss money. See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” Johnny, narrating, gives a raspy cackle the way a drunken Polly might. I thought a jolly bonnet might be a euphemism for vagina, given the English propensity for twee vulgarity. But Polly just had a new hat.

Johnny leads us to the busy intersection of Brick Lane and Thrawl Street. Today, Brick Lane is lit brightly with loud neon signs and lined with curry houses where restauranteurs coax tourists inside. The sidewalk is packed. “Places like Brick Lane have so much cultcha,” Johnny points out. “But 30 years ago, you would find yourself in the poorest district in all of London.” Even now, the most modern sign appears to be from the ’70s. I don’t think Victorian disco was the intention, but neither was city planning.

“If you came down here back in the day, you’d want to get out pretty quickly, because this was the slum district where the criminals and prostitutes all used to live and work. When they weren’t out pimping and whoring, they were usually out drinking. That building right there was once Ye Frying Pan Pub.” We look up to see the red clay with the words ye frying pan carved in relief next to a pair of crossed frying pans that could just as easily be tennis rackets.

Polly Nicholls was the first victim in the Canonical Five. She was last seen at 2:30 a.m. by her friend Emily Holland. She was staggering drunk and boasting about making four nights worth of lodging, “I’ve had me doss money three times today and spent it. It won’t be long before I’m back,” she told Holland and went away from the Thrawl Street shelter where she had been refused entry. That was the last anyone saw Nicholls alive.

Charles Cross happened upon her body around 3:40 a.m. as he walked to work along Buck’s Row. At first, Cross mistook the body for a discarded tarpaulin that he might use in the course of business as a carter. Upon closer look, he found Nicholls lying in the entryway of a garage just past a row of cottages. The body was cold to the touch, but Robert Paul, a fellow carter who ran into Cross minutes later, thought he felt movement in her chest. Rather than touch her again, the two men, running late for work, left Nicholls and alerted the first constable they encountered.

There was so little blood, or none seen without a lantern, that Cross and Paul simply pulled her skirts over her to cover her exposed body without noticing how garish her wounds were, or even that she had any.

Police Constable John Neil arrived on the scene and immediately saw how close to decapitated she was. There was no arterial spray from the two slashes that moved across her throat from left to right (precisely as would be done to the next victim), and that led authorities to believe Nicholl’s body had been moved to Buck’s Row postmortem. The other, more plausible explanation was that she had been strangled to death before her throat was cut. Without a heartbeat, the blood just oozed beneath her rather than pulsed from her arteries. Once the body was moved to the mortuary and identified, the full extent of her mutilation was revealed: She had been cut from groin to sternum, exposing her intestines. The killer had also stabbed her numerous times in her sex organs—similar to Martha Tabram’s mortal wounds.

Police were now paying attention. But they didn’t know who they were looking for. A mad butcher was a known menace in Whitechapel, and went by the name…. “Leather Apron!” Johnny shouts with the enthusiasm of a mob ready to take down the murderer (he loves his job).

Detective Frederick George Abberline, a 14-year police veteran, wasted no time looking into who Mary Ann Nicholls was: Did she have debts? Enemies? Investigating motive turned up nothing. No one had a bad word to say about her. And she was poor—as were all the victims—so simple robbery could be eliminated outright.

Leather Apron, a shoe cobbler, was suspect where the women of Whitechapel were concerned. His name was John Pizer (or Piser), and he wielded a knife and threatened to rip women apart if they didn’t hand him their wages. It was the next victim, Annie Chapman, that elevated him to prime suspect.

“Once again I’m showing you another comparison photo of what this area used to look like in 1888 to how it does today—even though on the other side of the road, you don’t really need much prompting, because these buildings haven’t changed in about 250 years, OK? Where you stand right here was 29 Hanbury Street, and that used to house a great deal of businesses back in the day. You sold packing cases. You sold cat food.”

Like Mary Ann Nicholls, Annie Chapman worked as a prostitute. Both women had been married, but those marriages had ended. Neither had been born into poverty, but there was little else available to women abandoned by their husbands.

“Dark Annie” as Mrs. Chapman was known, sold crochet work and lived at Crossingham’s Lodging House in Dorset Street. She was provided a nightly bed by a man locals called “the Pensioner,” because he was believed to have retired from the military. During the inquest into Annie’s death, he was discovered to be a brick layer named Ted Stanley. In the days leading up to her death, Annie was involved in a catfight with another female lodger, Eliza Cooper, at a pub, and many suggested Ted Stanley was at the heart of the dispute. Annie suffered blows to the face and chest. In the end, the fight was over soap, which Annie had borrowed to lend to Ted but neglected to return. Annie threw a half-penny at Eliza and told her to go “get a half penny’s worth of soap.”

The Dorset Street area was lined with lodging houses packed with people not much better off than the homeless. Some of the doss houses held 400 people a night. Annie was gravely ill, suffering from tuberculosis and nearly starved, and likely would not have lived much longer even if she hadn’t succumbed to the Ripper. The evening before she died, she was seen by a friend who reported that Annie was to have gone to Stratford that day but was too ill. Whatever energy she could muster would have gone toward earning enough for a bed that night, but that goal wasn’t achieved. About an hour after midnight, the doss nightwatchman found her in the kitchen eating a potato and ran her off when she didn’t produce the money for a bed.

The church bells rang at 5:30 a.m. on Sept. 8 as a woman passed 29 Hanbury Street, where she saw a woman negotiating with a man wearing a dusty old coat and a peaked cap or deerstalker cap similar in shape to the one made famous by Sherlock Holmes. After subsequent murders, people reported seeing a man in a military or soldier’s hat. Both also have a peak in the middle.

“Will ya?” Johnny growls like a surly man who has spent the night drinking and is ready to release. Then he points at us to get Annie’s response.

“Yes!” we chime.

Moments later, a lodger with a mean urinary tract infection went outside for one of his frequent visits to the loo. His yard shared a fence with 29, and he heard a thud, as though a person had fallen. He returned to his home and left through the front door for work, but did not see Chapman or the companion that the woman passing by had reported. The street was empty. Thirty minutes later, John Davis, a resident of 29 Hanbury, walked out to his backyard and came upon Chapman’s desecrated body. The killer’s rage had escalated. Two cuts to her throat had sliced into her spine, she had been strangled, and her body had been flayed with her knees bent and legs spread. Her intestines had been removed and placed over her shoulder. Half of her bladder and the entire uterus were gone.

Left: The Police News, September 22, 1888, reporting the murder of Annie Chapman, the second victimRight: The Police News, 1888, reporting the murders of the third and fourth victims, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Public DomainAt this point, the search narrowed to suspects with working knowledge of a blade and anatomy. Everyone posits a surgeon as a likely identity for Jack the Ripper, but he could easily have been a slaughterhouse worker, a butcher, a barber, a veterinarian—all also skilled with a knife. And a surgeon would likely have stood out in Whitechapel due to his fancier attire and access to a bathtub while the others were common jobs for men in the area. Indeed they were the honest trades of many of the 20,000 Jewish men residing in the area. And a workman’s apron was found at the 29 Hanbury crime scene.

“The English had a lot of apprehensions around the Jews,” Johnny says. “They believed no Englishman could do that to an Englishwoman. So that bred a lot of anti-Semitism. Jews were beaten in the streets, their windows smashed in, and ‘Leather Apron’ was hissed at them.”

The rioting brought large numbers of police to the streets of Whitechapel. There was now a murderer at large and a race riot. Creepy John Pizer, the threatening Leather Apron women had suspected in Mary Nicholls’s murder, was hauled into custody, but his alibis were solid, so he was returned to his hovel. The apron found in the yard belonged to John Richardson, the homeowner’s son. He had been on the back steps cutting leather from his boot with a

The row houses all had front doors leading straight through the house to a backdoor and yard, a straight shot front to back. It’s difficult to imagine all of these people were out front and in the backyards of two adjacent apartments in the 30-minute window between Annie seen alive and Annie found dead without a definitive witness.

The killer waited almost a fortnight, until the rioting subsided and the police went away. Then, on Sept. 27, the Central News received an ominous letter written in red ink with the greeting, “Dear Boss.” He had claimed to attempt the letter using blood, but it had congealed. Among other things, he wrote:

“That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was.” Clearly, he wasn’t happy with the name the press had attributed to his “work.” So, he signed the letter:

“Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Don’t mind me giving the trade name”

"Dear Boss" letter, postmarked and received September 27, 1888

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Public DomainTwo days later, the letter was forwarded to Scotland Yard and dismissed as a hoax, until the body of Catherine Eddowes was found the following morning. After that, headlines began using “Jack the Ripper” on stories about the Whitechapel murders.

“People were very susceptible to what was in the newspaper, because most of London were illiterate at the time,” Johnny says. “The tabloids would really lay it on thick. Everything was illustrated. Photographs weren’t in papers in those days. So, they could just show whatever the hell they liked—crime scenes, cops, potential suspects, and what the victims look like before and after. It didn’t matter if they were accurate.”

When Johnny’s voice rises we stop. “Well, guys, it took us a long time, but Welcome to Ripper-Vision ™!” He says as he beams a grainy photo of Elizabeth Stride’s autopsy photo onto the side of the wall. “She looks like Lionel Ritchie,” he says.

In the rainy witching hours of September 30, the Ripper struck twice, ostensibly because his first attempt was thwarted by witnesses. The “Double Event” was not the culmination Jack the Ripper’s voracity. But it was close.

Elizabeth Stride had spent the evening cleaning the doss at Flower and Dean streets where she had lived for most of the decade. After cleaning two rooms and earning sixpence, she took off to drink at the Queen’s Arms pub.

Stride was an enterprising woman who was only an occasional prostitute. Born in Sweden in 1843, she moved to London in 1866. In Sweden, she had been on a registry of known prostitutes and had been treated for venereal disease many times. After taking a position as a domestic, she was no longer on the prostitute list. Three years after arriving in London, she married John Stride, and in 1869, they opened a coffee shop, which they ran until they separated in 1881. She moved to Brick Lane and was living in Whitechapel where she had three jobs: charwoman, seamstress, and translator. “She spoke four languages, English, Swedish, German and Yiddish. So she was often a translator for Jewish businessmen,” Johnny tells us. “I think she’s amazing. Unfortunately, her then boyfriend in 1888, a fellow named Michael Kidney, stole her money, and she began selling her body just to get by.”

Around half past midnight, Elizabeth Stride was seen outside a place called Dutfield Yard with a man in the same dark peak hat and dusty old coat Annie Chapman’s companion was said to have worn three weeks earlier outside 29 Hanbury. According to an eyewitness, police officer William Smith, the two were standing where Stride would be found dead. He later identified her by the flower she wore in her waistcoat. But as he passed them, nothing seemed amiss.

It was close to 1 a.m. when Louis Diemschutz’s horse-drawn cart pulled into Dutfield Yard. In the gloomy night, visibility was low, but his horse was startled and shied away from something. Curiosity piqued, Diemschutz lit a match and saw Stride wounded with fresh blood flowing from her throat. It is very possible that Jack the Ripper was interrupted, and if he had looked up while the match was lit as he knelt before Elizabeth Stride, Louis Diemschutz would have seen the Whitechapel murderer.

On the other side of the road is posh EC1, the City of London. What is now the financial district with skyscrapers was long ago fortressed by a great wall that the Romans built some 2,000 years ago. Remnants of it can still be seen near the Tower of London.

On the evening of Sept. 29, Catherine Eddowes was on the fringes of the City of London where she sang out to bemused onlookers, “Ding! Ding! Ding! I’m a fire engine!” At 8:30 p.m. on Sept. 29, police hauled her to the nearest station, Bishopsgate—named for one of the seven gates in the wall that the Romans built—for drunk and disorderly behavior. She gave “Nothing” as her name during intake.

After midnight, on Sept. 30, Jack stretched a leg from the muck of E1 into EC1, now the financial sector inside the Square Mile. Right about then, Elizabeth Stride’s body was found.

Like the women before her, Stride’s throat was cut ear-to-ear. Gruesome though it was, there was no mutilation to her body. She was not ripped open. “So, maybe the killer was still there when she was found,” Johnny suggests.

About four hours later, at a quarter past midnight, Catherine was heard singing in her cell. A few minutes later she asked an officer when he’d spring her.

“When you can take care of yourself,” he answered.

“I can do that now,” she said.

He let her out of her cell and asked again for her name and address, “Mary Ann Kelly of 6 Fashion Street,” she lied. (Ironically, Mary Kelly would be Jack the Ripper’s next and final victim among the “Canonical Five”.)

As he escorted her to the door, she asked for the time to which he replied, “Too late for you to get anymore drink.”

"I shall get a damned fine hiding when I get home," she shrugged. (Her companion, John Kelly, had gone to the lodging house at 8 p.m., and stayed there the entire night after pawning his boots.)

“Serve you right,” the policeman said. “You have no right getting drunk.”

As she walked out the door, she shot back, “Good night, old cock.”

Eddowes left the police station and headed deeper into the City of London, because she knew exactly where to earn four pence: Prostitute Island!

“Prostitute Island was quite a remarkable place in the City of London,” Johnny explains. “It’s where the ladies of the night would go and ply their trade, and the City police wouldn’t arrest them for it. Some say it was because it was on holy ground, being situated within the churchyard of St. Botolph’s without Aldgate. But the main reason the girls went there was because the rector allowed it. It was safer for them to solicit there than out in the streets.”

By 1:35 a.m., Eddowes was seen standing in the darkest part of Mitre Square accompanied by a man in a dark peak cap and dusty old coat. And that eyewitness gave a vivid description of the guy: 5’7”, mid-twenties or early thirties, with a red checkered bandana around his neck.

Left: September 1888 Newspaper BroadsheetMiddle: September 21, 1989, Puck MagazineRight: Punch Cartoon 5, 1888

Photo Illustration by Daily Beast/Public DomainInto Mitre Square we trudge. We have been walking a good hour.

“Wow, Jack the Ripper really got around,” I say as we traipse behind Johnny.

“Jack the Walker,” a man chuckles. “They had to be looking for somebody fit.”

It’s now very modern, no longer surrounded by slaughterhouses or butchers, but as it also then housed the largest consignment of tea and coffee in all of the British Empire, it was guarded by watchmen and patrolled by a beat cop every 15 minutes. The skyscrapers in the city of London weren’t there yet of course. A playground is nearby, but would have been part of the industrial map where Eddowes and her companion were enveloped by the very darkest corner “where a set of Georgian houses were just jutting out.”

Less than one hour after leaving the Bishopsgate police station, Catherine Eddowes was dead. Mitre Square, a busy area by day, had been empty 15 minutes before when patrolman Edward Watkins made his 1:30 a.m. rounds. At 1:44 a.m., he returned to find her body in a pool of her own blood, savagely cut apart with her skirts haphazardly thrown over her waist exposing her legs and her intestines placed over her right shoulder. Her bonnet and scarf around her neck were still in place, although her throat had been slashed and her windpipe severed. Watkins blew his whistle and summoned retired cop and nightwatchman George Morris, and the two set off to get help.

After the postmortem examination, the horrific details emerged. Jack ripped her from anus to breastbone. Her left kidney was removed as was part of her womb. The tip of her nose and eyelids were cut away.

In the Dear Boss letter, Jack had written, “The next job I do I shall clip the lady's ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldn't you.” Part of Eddowes’ ear was indeed cut off.

On Goulston Street between the flats that lined either side of the road just a short distance from Mitre Square, the missing piece of Catherine Eddowes’ apron was found with fecal matter and blood on it. There was also graffiti nearby that read: “The Juwes (sic) are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.” It was hastily removed to avoid widespread panic and anti-Semitic backlash. Whether or not it was a message from Jack is unknown. The only photographs of it are reproductions.

Truly, if you do not want to see a billboard-sized photograph of Catherine Eddowes’ autopsy photo, Ripper-Vision isn’t for you. From the looks of it, Eddowes is on a table, but there were no overhead cameras back then, so she is hung by a meathook and the photograph is taken as though she is standing up.

The investigation ramped up. Sniffer dogs were sent out to look, but the inundation of human scents on the dirty streets yielded nothing. The tabloids were nuts. People were on guard. Patrolmen were everywhere, and all possible suspects were brought in for questioning. With all this going on, one thing wasn’t happening. Jack the Ripper stopped killing. He likely hid in plain sight, waiting for things to die down, so he could strike again. And he did. In November.

Mary Kelly, the last of the “Canonical Five” to be killed, lived in the Dorset Street neighborhood, which today, as Johnny explains, bears no resemblance to its 19th century description: “The 30 lodging houses, eight brothels, four pubs, and 2,000 of some of the worst people you could imagine—the sort of people that made Billy the Kid look like Winnie the Pooh—are gone.”

Mary Kelly had a room at 13 Miller’s Court that she accessed through a small door on Dorset Street. “Police officers wouldn’t go down Dorset Street unless they were armed with shotguns. And if a rich man made it from one end of the street to the other with his life, much less his wallet, he was considered extremely lucky.”

Kelly was only 25 back in 1888, the youngest of all the victims and the only one who had her own accommodations. On Nov. 9, she was in a bit of a pickle, because she owed 29 shillings in arrears to her landlord (about 100 pounds today.) It was earn-money-or-get-booted. At 2:30 a.m., she was seen outside Miller’s Court in the company of a man who looked to be well off in a fine suit, polished boots, a proper felt hat, and a fur-trimmed coat. But just behind him, according to witnesses, lurked a man in a dark peaked hat and dusty old coat. Fifteen minutes later, Mary was back in her room and overheard singing softly to herself.

Later that morning, the landlord sent a hulking debt collector to her flat. He pounded on the door, then went around to peer through a window that Mary had broken about a week before. What he saw would haunt him the rest of his life. Johnny projects the only crime scene photo taken during the Ripper spree, and to call it grotesque is an understatement. Kelly’s face was hacked beyond recognition. Her estranged boyfriend was only able to identify her by hair and eye color. Her throat was cut ear to ear and the one thing keeping her head attached to her body was her spine. Both her breasts were excised, and her abdomen was scooped out. Her intestines were on the bedside table. Her sex organs were placed under her head alongside one of her breasts. The flesh from her thighs was peeled down like a pair of stockings, exposing bone. The only thing missing from the room was her heart.

Why is this case still so riveting?

Is it the cinematic ambiance of Victorian women in bonnets, corsets, and skirts with gentlemen wearing tophats in shadowy lamplit alleyways while a silhouetted, caped killer elusively stalks women? Today, the archways and cobbled streets inside the low, cloistered buildings are still as we imagine they were a century ago, minus the gas lamps with yellow halos barely able to light an area much larger than a foot of soot-filled air after midnight. Of course, the imputed romance is a sham. Most people in 19th-century Whitechapel were unhealthily corpulent, alcoholic, missing teeth, variously diseased, flea-bitten, lice-ridden, and scabrous under layers of filthy clothing.

Is it his perfect name? Our tradition of naming serial killers—Night Stalker, Hillside Strangler, Toybox Killer—began with Jack and continues long after he himself returned to dust.

"From Hell" letter, postmarked October 15, 1888

Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Public DomainIt must be said that Jack the Ripper, if the man who signed the letter written to the press with that moniker was indeed the murderer, presciently nicknamed himself. Perhaps London’s then-new tabloid culture—with its sensational headline-grabbing details and illustrations that resembled a salacious graphic novel—encouraged a romanticized version of the lives led in Whitechapel during these frenzied killings, killings that unsettlingly ceased as abruptly as they began and were never solved.

At the final stop of the tour, Johnny summarizes each case and current theories as to all the suspects. Our surroundings as we listen to the litany are unsettlingly appropriate: Around us are multiple pubs crowded with post-work drinkers, now several hours into their cups. A high proportion are young women (the British attitude to excessive drinking is far more laissez-faire than in other countries), and we watch a series of staggering girls reel mostly unaccompanied to find their way to buses and trains. One of them tries to steal an unlocked bike but is too drunk to even figure out how to hold her balance—the lack of a faceplant is amazing—and she wisely abandons it and continues off unabashed. The realization that a modern-day Ripper could still find easy pickings in these parts is the chilling conclusion of this tour’s journey.