The phone-hacking scandal that has upended the British political and media establishment has expanded to Australia, where the federal police have contacted a businessman once at the center of a tabloid scandal known as Cheriegate—as it involved Cherie Blair, wife of former prime minister Tony Blair—to inform him that, he too, may have had his telephone hacked.

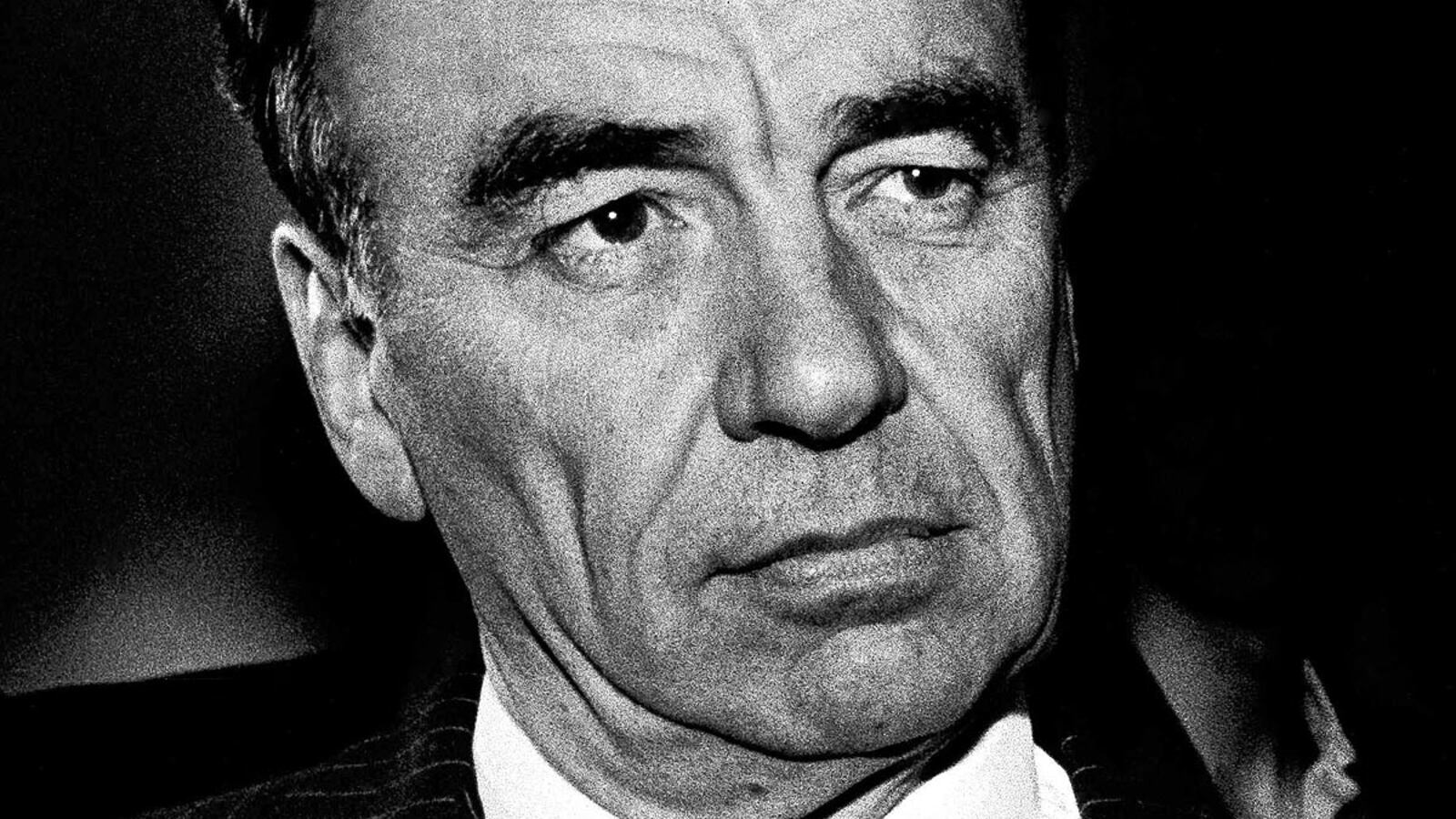

The businessman, Peter Foster, told The Daily Beast in a phone interview on Monday that he recently was told by Australian officers, acting on behalf of the British police, that detectives had found his old mobile phone number and data relating to it on a computer in London, suggesting his phone had been hacked. (The Australian Federal Police confirmed in a statement that agents had visited Foster but would not comment further.)

In a twist that could spell further trouble for Rupert Murdoch’s London-based tabloids, Foster claims he also was contacted last week by a Dublin-based private investigator, who said he had been working for The Sun newspaper through a London agency at the time of the scandal.

The Australian businessman, who has been convicted in both the U.K. and the U.S. for scams involving health-care products, helped the Blairs buy property in Bristol, and he and his then girlfriend, Carole Caplin, attended various social events with the prime minister and his wife. After Foster’s criminal record came to light, Foster and Caplin split up, and Foster returned to his birthplace on the Gold Coast in Queensland, Australia.

According to Foster, the investigator told him that, for four days at the height of Cheriegate, he had been sitting with another detective outside Foster’s mother’s flat in the Dublin suburbs, intercepting and recording the calls to her cordless landline.

Though the investigator refused to be identified, Foster said he believes the man’s claims to be genuine, because the investigator could recall conversations Foster had had with his mother that were never made public, and because of the investigator’s ability to describe his mother’s apartment.

Foster told The Daily Beast that, until last week, he had always assumed it was his London landline that had been bugged, perhaps by the security services. It had never occurred to him his mother could have been the target, he added. He also said he would willingly submit evidence to the Leveson Inquiry, which is looking into practices of the British press, merely to set the record straight. “We didn’t know what was happening ... Carole and I got quite paranoid. When those tapes came out I thought, oh-oh, this has gone too far. Now the spooks are involved.”

Until mobile-phone signals were digitized in the late 1990s, they could be intercepted with a handheld scanning device. In 2000 a new act was passed in the U.K. that made intercepting a conversation in the course of transmission illegal. Under Irish law, it is also a crime to intercept phone conversations without authorization.

In December 2002, The Sun newspaper published a front-page exclusive it called “The Foster Tapes,” which were based on a transcript of calls between Peter Foster and his mother.

The Press Complaints Commission upheld Foster’s complaint about the interception of the private calls, agreeing there was no public interest in the material and concluding that “eavesdropping into private telephone conversations—and then publishing transcripts of them—is one of the most serious forms of physical intrusion into privacy.” The Sun’s editor at the time, David Yelland, was forced to print an apology.