Mr. Madison’s Slaves

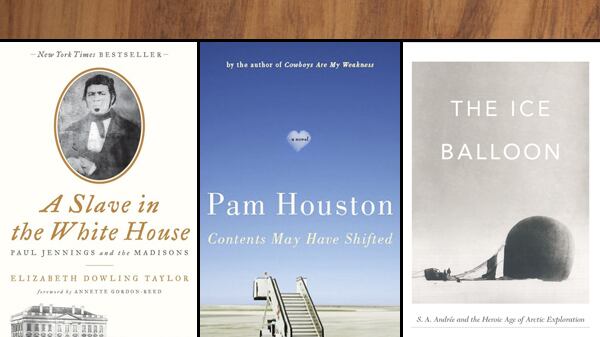

A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the MadisonsBy Elizabeth Dowling Taylor.Foreword by Annette Gordon-Reed.336 pages. Palgrave Macmillan. $28.

It has taken awhile, but James Madison finally seems to be emerging from the shadow of Thomas Jefferson. For generations, both the public and professional historians had relegated him to a sort of second-tier Founding Father status, the obsequious acolyte of Jefferson, who, it was thought, Madison was inferior to in every way. Five foot six to Jefferson’s towering six foot three; eight years Jefferson’s junior; more a secretary than a leading voice at the Constitutional Convention.

But only in the past few years has that changed. Historians, with the help of recently published volumes of his papers, have come to see Madison as the true luminary he was: not only was he a dominant author of the Constitution and The Federalist Papers, but also largely responsible for the Bill of Rights, which defended minority rights against encroachment by the federal government. Not since John Locke has there been as articulate a defender of religious freedom as Madison, we now know. And, of course, he was our fourth president, elected twice.

There is a risk to all this approbation, of course, which is that we forget some of his failings. Perhaps most important, and least explored, is his record on slavery, which makes Elizabeth Dowling Taylor’s new book, A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons, so important. Taylor is less concerned with Madison’s thoughts on slavery than she is with how Madison actually treated his slaves—and one in particular, Paul Jennings, his long-time personal servant.

Jennings was born in 1799, on Madison’s Virginia plantation, Montpelier. Like all his hundred-odd slaves, Madison inherited Jennings from his father, a wealthy Southern planter. But as Taylor makes clear, Jennings was no ordinary figure. He used almost every opportunity available to eventually buy his own freedom, which he did in 1847, and helped many other slaves escape to freedom as well. “He knew how to succeed within the system in which he was trapped,” Taylor writes. “He was good at what he did, always the unobtrusive figure in the background, there to attend to his master’s needs … But Jennings was also good at gaming the system, judging when to stretch or risk his ‘place,’ and not lacking for courage to follow through.”

Jennings was fortunate to be born into a powerful family, of course. Without the Madisons, he would likely never have met the men—Daniel Webster, Lafayette, Edward Coles—who emboldened his pursuit of freedom and, in Webster’s case, helped Jennings secure it. To Taylor’s credit, she also notes Madison’s own relatively benign treatment of his slaves, even though, as she concedes, he was in the end a “garden-variety slaveholder.” Still, Madison refused to allow his slaves to be whipped, and he stipulated in his will that his wife, Dolley, never sell a slave without the slave’s consent.

This is hardly apologetics. Taylor, who has a Ph.D. from Berkeley and for many years was a historian at the Montpelier estate, balances this portrait with a scrupulous unearthing of the plantation’s less-than-noble reality. She quotes a letter from Madison’s stepson, who attests that floggings happened plenty, though presumably while Madison was away. And she finds that, in direct contradiction to Madison’s will, Dolley began selling off the slaves not long after her husband died in 1836, at 85. In a newspaper article Taylor discovers from the 1880s, one of those slaves, Ben Stewart, is quoted as saying: “During the days of her poverty [Dolley] sold off her servants one by one, and I remember I was bought by a Georgia man.” “I supposed she got about $500 for me,” he continues, “and if she did I was cheap at that.”

Taylor leavens this morbid tale with Paul Jennings’s remarkable story. All that remains from his own testament is a short biography he published in 1863. But she carefully speculates that at least some (though not all) of the oral testimonies passed down to his descendants were, in fact, true. When the British nearly burned the White House to the ground, in the War of 1812, Jennings helped save the massive portrait of George Washington that greets visitors to this day. He probably forged freedom papers for a number of slaves escaping to freedom in Washington. And he almost certainly helped 77 more slaves escape on the unsuccessful “Pearl” rescue mission, the largest attempted slave escape in American history.

This tells us a great deal about Paul Jennings, and how difficult it was for even a well-connected and remarkably intelligent man like himself to gain his freedom. But what does it tell us about Madison? Alas, this may be the book’s only signficant flaw. Taylor admits early on that she’s more interested in Madison’s character than she is in his thought. While she highlights some of the few surviving documents that evince his views on slavery—“Great as the evil [of slavery] is,” he wrote in 1788, “the dismemberment of the union would be worse”—we’re left searching for how his ideas about natural rights and individual liberty might have informed his notions of slavery, and vice versa.

Still, A Slave in the White House reminds us that even if Madison, like most the slaveholding Founding Fathers, were intellectually opposed to slavery, they didn’t think much of blacks themselves. “Generally idle and depraved,” Madison wrote in 1823, in response to a questionnaire about free blacks, “appearing to retain the bad qualities of the slaves with whom they continue to associate, without acquiring any of the good ones of the whites.” And as Taylor points out, Madison actually did want to eradicate slavery from the nation he did so much to create—yet only on the condition that blacks be removed from the nation once they were free. His response to that same questionnaire on this point is revealing, however. When asked if there was any general plan for emancipation, and if so, what was it? Madison answered succinctly: “None.”—Eric Herschthal

Up, Up, and Away!

The Ice BalloonBy Alec Wilkinson256 pages. Knopf. $25.95.

In 1895 a Swede named S.A. Andrée began telling fellow scientists of his bold plan to build a state-of-the-art hydrogen balloon and fly it to the North Pole. Previously, men who’d tried to scout similar terrain had done so with the aid of dog-propelled sleds—and most of them had died in the process. Andree, for his part, wasn’t an experienced explorer, and he’d chosen a notoriously unreliable mode of transportation. What chance did he stand?

Andrée himself must’ve known that success was a long shot. Yet as he mapped out his journey, says Alec Wilkinson in The Ice Balloon: S.A. Andrée and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration, the fledgling aeronaut was confident, if mordantly so. Writes Wilkinson, “When asked what he would do if his balloon came down in the water with no one around, he said, ‘Drown.’ ” Though Andree wouldn’t have to worry about swimming to safety, Wilkinson’s stirring and artfully wrought book makes clear that he and his small crew confronted dozens of other challenges as they set out to sail, and then hike, across hundreds of miles of punishing ice.

Subzero temperatures, fatigue, injury, starvation, potential foodborne disease, psychotic episodes induced by any number of factors, animal attacks, unrealistic ambition—Arctic adventurers battled each of these, which explains why so many of them didn’t come home. “Before the twentieth century,” Wilkinson writes, “more than a thousand people tried to reach the pole, and according to an accounting made by an English journalist in the 1930s, at least 751 of them died.”

Odds be damned, Andrée and his two-man team lifted off from Dane’s Island, a Norwegian land mass north of Sweden, on July 11, 1898. Amidst the extensive press coverage—the journey, Wilkinson notes, made the cover of The New York Times—Andrée was quoted as saying that “one year, perhaps two years, may elapse before you hear from us.” In fact, it would be more than three decades.

Lest the reader be conned into a false air of suspense, Wilkinson makes clear from the first chapter that Andrée and his team were doomed, their bodies undiscovered until a group of Norwegian scientists stumbled across them in 1930. Aware that some of his readers will know this already, Wilkinson focuses not on the results of the mission but on the culture that spawned such brave and heedless exploration, and on the men who volunteered for work with such a high mortality rate.

While many of his contemporaries framed their quests in grander terms, Andrée seems to have been driven by a wholly rational impulse. “He didn’t see himself as a solitary figure measuring himself against the wilderness and the elements, or as someone trying to wrest from nature its secrets,” explains Wilkinson, a staff writer at The New Yorker. “Or even, as some did, a man in a headlong approach toward the seat of the holy. He was an engineer who wanted to prove the validity of an idea and he had found a forum in which to enact it.”

Andrée set out to demonstrate that balloons could do what bipeds couldn’t. Balloon travel had been on his mind for more than 20 years—he’d sought out a Philadelphia-based balloon aficionado when he was in the States for the 1876 Centennial Exposition—and by the mid-1890s he’d convinced a significant portion of the Swedish intelligentsia that his vision was a viable one. With funding from, among others, Alfred Nobel, he designed an ultramodern balloon, one that he liked to say “included seventy innovations, thirty of which he thought of himself,” Wilkinson writes.

Out in the elements, Andrée’s balloon apparently didn’t behave like he hoped it would, but more than 100 years later, there’s much about the end of the expedition that simply “isn’t known,” Wilkinson says. Having begun his book by revealing his protagonist’s fate, Wilkinson ends The Ice Balloon in fascinating ambiguity. Nonfiction storytelling doesn’t get much more ingenious.—Kevin Canfield

Of Wanderlust and Sadness

Contents May Have ShiftedBy Pam Houston306 pages. W.W. Norton & Company. $25.95.

Pam Houston talks about the “in-between place” between fiction and non-fiction. Her writing exists in this unnamed area amid fact and fabrication. Her fiction relies on her experience; her nonfiction, as she’s said, wouldn’t stand up to Oprah. Cowboys Are My Weakness, her first collection of short stories, one which lassoed tremendous attention, was peopled with gutsy, flirtatious, life-hungry women, wise enough to know their choices weren’t always the right ones. What captivated readers was how true these stories felt—you didn’t have to run rapids or confront grizzlies or sleep under a moose pelt to hear Houston’s warm and genuine voice telling you about women and men and women and women and freedom and love and sex.

Contents May Have Shifted, her new book, 20 years after Cowboys, travels some of the same territory and exhibits a similar questing, questioning exuberance, albeit tempered slightly by two decades of learning and experience. What was brazen and unapologetic in the women of Cowboys has evolved to something bold, still, but a little humbler.

Originally titled 144 Good Reasons Not To Kill Yourself, the book is billed as a novel because you have to give names to these things. It includes 144 episodes narrated by a woman named Pam that crisscross the earth, each chapter named for the place they happen Alsek Bay, Alaska; Drigung, Tibet; Zaafrane, Tunisia; Stone Harbor, New Jersey; Bumthang Valley, Kingdom of Bhutan; and 12 harrowing plane rides. “I know all about the anatomy of restlessness,” she writes. The book is a portrait of restlessness, of finding the elusive moments and places when “you are truly in the center of your life.”

The loose narrative arc involves Pam disentangling herself from one rotten relationship (loathsome, lying Ethan’s got women in a couple different countries, and the descriptions of him are reminiscent of sections of Anne Carson’s Plainwater: “Ethan always says the fruit in America doesn’t have any taste ... He says once you have eaten a Costa Rican mango, an American mango tastes like shit,” quietly damning). That romance ends, another begins, and all the while Pam is on the move, spending time with her dogs and pals, traveling, teaching. It feels in part like carpe-dieming, and part like escaping.

Her gleeful, curious, childlike embrace of the world—particularly the natural world—is hard to resist. Big rushing waves on a river “make me want to do cartwheels, to give indiscriminate kisses, to hit somebody in the face with a pie.” Behind the wanderlust excitement, sadness and pain follow. “It is hard not to wonder,” Pam muses, “whether we use the small sadnesses in life to avoid or to access the large sadnesses.”

Her various sadnesses are treaded gently, and run deep: a body worker asks if she’s got scarring by her pubic bone. “Which I do, of course, because of all of the shenanigans my father got up to when I was a very small girl and the subsequent surgery I had at sixteen, performed (hush, hush) by his urologist to remove some percentage of the damaged tissue that was so large it was creating infections down there.” Such horrors are revealed as matter-of-fact.

Some of the episodes can feel a bit like riddles, ones that can’t quite be answered, and frustrating for it; the significance of certain encounters and experiences can be difficult to locate. And a swirl of friends and healers get blurred at times. But Houston is generous and genuine in her storytelling, where the truest place turns out to be where imagination interprets experience. Lines from Cowboys hold true: “I thought about the way we invent ourselves through our stories, and in a similar way, how the stories we tell put walls around our lives.” With this new book, Houston continues to invent herself, sharing kernels of wisdom and warmth, maintaining a spirited flirtation with the world as she exists in it.—Nina MacLaughlin