The San Fernando Valley is the kind of place where the A/C is on year-round and almost everything is a shade of brownish-gray, either a “coming soon” construction site or some anonymous strip mall, sun-bleached and covered in a light film of dust.

When people think of L.A. traffic, they’re thinking about the Valley, where the 101 and 405 slow down to a bumper-to-bumper crawl; but the relatively affordable housing, pool to person ratio, and untouched hiking trails do make it a pretty nice place to live.

For a tourist, however, there’s no real reason to sit in a rental car for two hours. Unless you’re making the pilgrimage to the Chuck E. Cheese in Northridge, home to what was intended to be the sole remaining Mr. Munch’s Make Believe Band.

ADVERTISEMENT

When Chuck E. Cheese announced last November that Mr. Munch’s Make Believe would be disbanding after almost 50 years, the company decided to keep the band at one “legacy” location, which turned out to be Northridge. And the result, according to CEC Entertainment’s Head of Public Relations, Alejandra Brady, has been a significant increase in childless adult visitors, who are making a special journey to see the quintet.

On the heels of this development and an “outcry” among fans, Chuck E. Cheese revealed its decision to keep the animatronics alive at four additional stores in Pineville, North Carolina; Hicksville, New York; and Springfield, Illinois. Not to mention, the “Studio C” show at the Nanuet, New York, location, where Chuck E. will perform a solo set—hopefully, a raw and stripped-back studio cut of the iconic “Birthday Star” song. Or, if corporate remembers my suggestion, the Johnny Cash version of “Hurt.”

While millennial nostalgia alone can’t revive the animatronics industry or stop a new generation of kids from preferring interactive LED floors, our tendency to romanticize a time when life wasn’t just doomscrolling and near-constant anxiety is worth considering. And if there’s one place most millennials associate with childhood, it’s Chuck E. Cheese, whose brand identity is deeply tied to these fuzzy robots.

In my memory, Chuck E. Cheese is a sugar-surged vision of bright teal booths, plastic tablecloths, and kitsch decor; flashing lights, the squeak of rubber against linoleum, and a room pulsing with pure joy. There’s the jingle of brass tokens, the sound of machines printing prize tickets, and the rush of excitement that comes with seeing a bunch of paper coiled around your feet. The birthday boy zooms past, dad chasing him with a clunky VHS camcorder until he gets tangled in a cluster of plastic balloons, while his mom is trying to wrangle the kids crawling on-stage to sing with Mr. Munch’s Make Believe Band.

However, I was a scaredy-cat baby, the kid who cried through the show before running away from the dancing guy in the Chuck E. suit. “But looking back, it’s actually kind of a nice memory,” I tell my partner while walking into the chain restaurant. They were times where I’d hide behind my mom’s Laura Ashley dress, which, knowing her, she probably just washed. “But she’d still let me use it as a tissue, and always stroked my hair until the set was over.” My partner jokingly pets my head, as we sit at the very end of a long banquet table that says “Happy Birthday, Sandra!,” even though I was born in July.

Happy “birthday” to me.

Sandra SongThe curtains are still raised from Chuck and friends’ last routine, but my former nemeses are more fragile than I remember. You can hear the metal click of their joints, the clap of their eyelids, and the herky-jerky movement, even when they aren’t playing. They’re actually really cool upon further inspection, I say.

There’s Mr. Munch’s retro-future ’80s synthesizer, Helen Henny’s ’90s icy blue eyeshadow, Jasper T. Jowls’ cowboy chic, and Pasqually the Pizza Chef’s wiggling mustache. But by the time my partner starts to grumble about Pasqually’s drumming technique, I’ve moved on and am drinking a White Claw. Apparently, Chuck E. Cheese has always had alcohol, as store manager Bri Traylor, 21, tells me. The only catch is that it’s a drink per hour, with a hard cap at two. It could have something to do with the fact that they used to serve beer pitchers during shows.

As McLeanas explains, the animatronics were invented by founder Norman Bushnell to entertain the adults. As a 31-year-old smoker who got winded after a few rounds of skeeball and hurt their back trying to squeeze into a token-operated ride, I finally understand the appeal of just sitting down with a drink, able to appreciate how mind-blowing this tech must have been in 1977.

Hopefully, I’m not the only adult with less physical stamina than a toddler who’s had ice-cream cake, as Traylor says the Northridge location has been hosting more and more “parties for 28-year-olds and 30-year-olds who just want to say they celebrated at Chuck E. Cheese,” with some even flying across the globe to see Mr. Munch’s Make Believe Band.

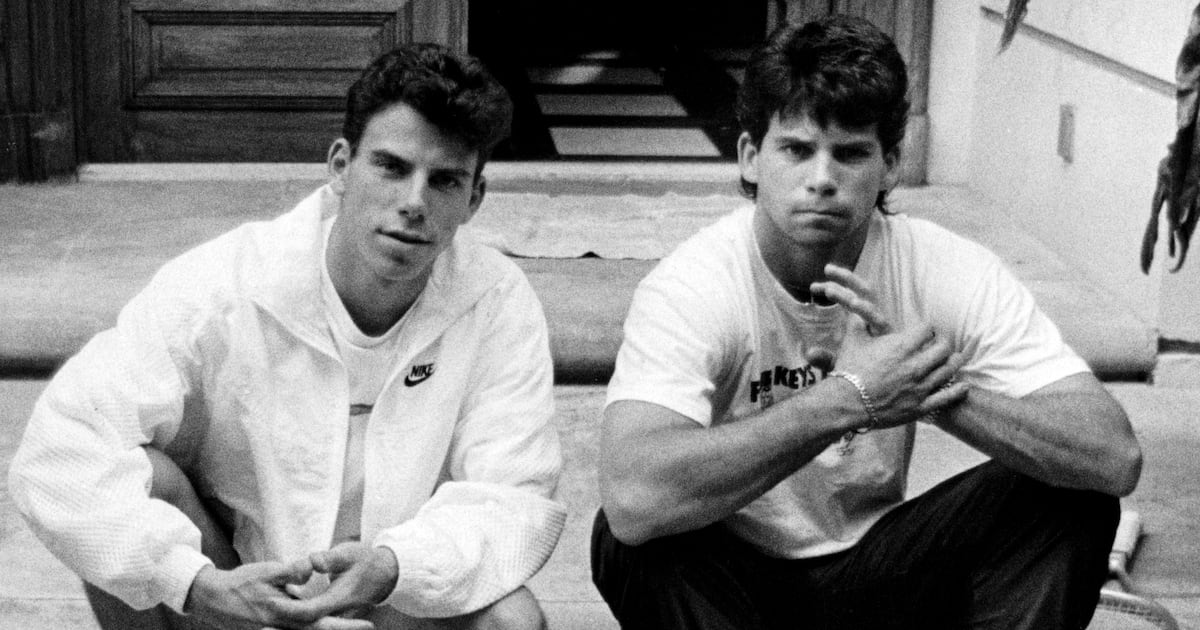

The Northridge Chuck E. Cheese’s mascot circa 1981.

Handout“Last week, we had someone from Australia,” Traylor says, before mentioning some Canadians who drove eight hours to see the band, only to learn they were out of commission that particular weekend. Traylor grimaces, “Oh my god, I felt so bad.”

That was a fluke, though, part-time employee Isaiah Nassab, 27, says. For the most part, the band is always ready to perform for the flood of childfree adults that travel to this “mini tourist attraction” from Texas, Arizona, and New Zealand.

“There was even a couple that came… and the guy came up to me and said his girlfriend absolutely loves Chuck E. Cheese and the animatronics,” the Chuck E. Cheese superfan recalls. “So he actually wanted to propose to her there.”

Nassab—who works in HR but enjoys picking up weekend shifts as a game attendant—explains that his family moved around a lot, meaning Chuck E. Cheese was one of the few constants in his childhood.

As someone with autism, the franchise and his familiarity with the shows made it his “comfort zone, where [he] felt safe and relaxed,” adding that “those characters [had] such a huge impact” on him, especially while he was “dealing with the challenges and the struggles of growing up [on the spectrum].”

As McLeanas, CEC Entertainment’s vice president of entertainment, says, it’s employees like Nassab who made the Northridge location the perfect place to house such an important piece of Chuck E. Cheese lore, adding that “I don’t know that I’ve ever worked for a brand that has this much passion.”

And it’s a passion that also extends to a fervent Chuck E. Cheese fan community, as content creator Matt Rivera, 36, explains. A prominent figure among Chuck E. fans, he sits in front of a complicated set-up of teal and purple lights inspired by the store’s old-school look. But in addition to being an excellent producer, Rivera is also creator of the “Chuck E. Con” convention, where superfans will come together to mingle, share memorabilia, and see performances from their favorite mouse. The rest of the time, Rivera says, they’ll hang out on Discord and a private Facebook group for “real” diehard fans who are “big on the nostalgia of Chuck E. Cheese,” mainly sharing stuff from “the late ’80s, early ’90s.”

Chuck E. looking as spritely as ever.

Sandra Song“We really love the in-house [animatronics] that Chuck E. Cheese did back in that timeframe, and even the 2000s too,” he adds. He then goes on to mention an older meet-up called “Cheesevention,” which happened about a decade prior to the recent round of remodels that got rid of these extra animatronics. Consisting of a tour bus of superfans, Cheesevention was an opportunity to visit every store between Los Angeles and the chain’s very first location in San Jose, California. The appeal, as Rivera explains, was walking around different showrooms, searching for any auxiliary animatronics from Chuck E. Cheese’s heyday, including secondary acts that would play in a separate “cabaret room,” and unique pieces of artwork with moving characters inside a faux frame.

At one point, the band begins to play, coming to life in order to wish me a very happy birthday. I can’t help but smile, even if I’m getting a little distracted by the video panel displaying a cartoon version of what the band’s doing right in front of me.

I’ll admit, watching it makes me a little sad, kind of like when I first entered the building and realized how small everything is. It’s unfair, because I’m comparing it to when I was 10, and it all felt like an enormous, expansive jungle of arcade games and skytubes.

When I was a kid, Chuck E. Cheese felt like entering the future. But as an adult in the actual future, there’s something about the bright airiness of the white-wall minimalist remodel and the lack of random tchotchkes crowding the walls, taken down to make space for LED walls and large screens for graphic-intense games.

I understand why, of course, but it’s almost dystopian to see a horde of 7-year-old boys using a scannable electronic wrist card instead of a token to start a game. Or the ring of parents standing right behind me, who can only watch their toddlers dance on top of an interactive dance floor through the lens of an iPhone 15.

The dining room of many a millennial’s childhood.

HandoutBut it’s the creak of Jasper’s swiveling head and the goofiness of Pasqually’s wiggling mustache that takes me back to that comfortable place, when I was a child whose only fear was of these incredibly sweet little robots.

In 1996, I never would have thought I would think of Mr. Munch’s Make Believe Band was anything but “terrifying,” let alone “familiar” and “calming.” Yet, here I was, on my hypocritical “old man yelling at cloud” type shit, despite having a sweet image of my dad, recording the show and my little brother dancing with an employee wearing a Chuck E. Cheese suit.

Suddenly, a door opens to reveal Chuck E. in the flesh, walking out to his animatronic self performing “The Chuck E. Strut.” He stops in the middle of the interactive dance floor, swinging his arms back-and-forth and getting a group of fascinated toddlers to dance with him. The smallest one begins twirling around at some point, but her chubby little ankles cause her to trip just as the show comes to an end. Chuck E. catches her, and she giggles. I feel a little emotional as I watch the curtain fall.