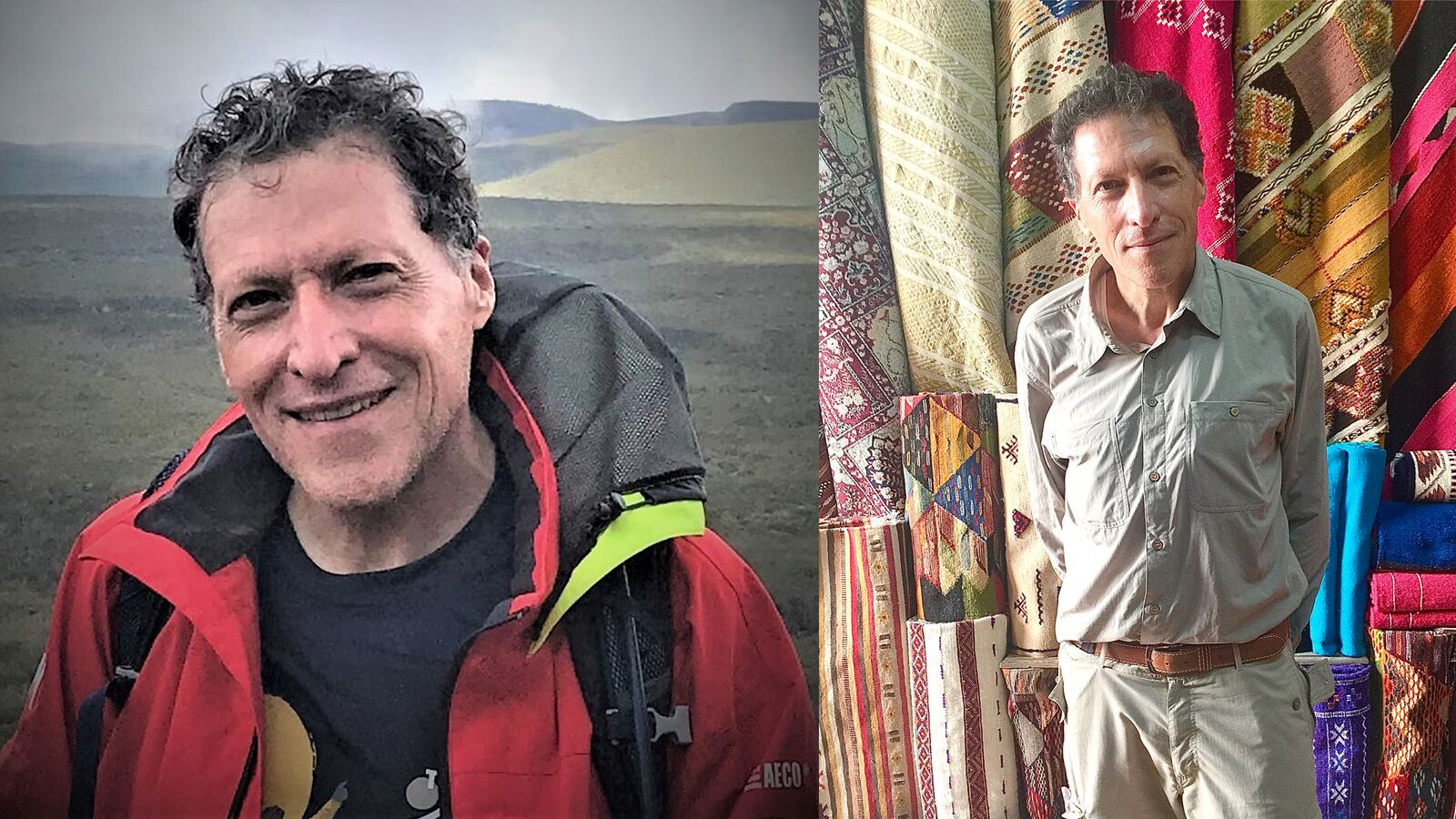

Even before becoming the editor-in-chief of Travel Weekly, the travel industry’s leading trade publication, in 2001, Arnie Weissmann was a globetrotter.

He circumnavigated the planet as a student (a lot less glamorously than he does now), then later as a travel journalist and then as founder, editor and publisher of Weissmann Travel Reports, a forerunner in delivering news and info to travel agents on every country in the world.

Weissmann is a very curious (and seemingly indefatigable) man whose wanderings have taken him to just about every nook and cranny of the planet. He’s been to 120 countries, “give or take,” and he loves food. He’s eaten at some—maybe at most—of the grandest and best restaurants on Earth, and he’s shared meals with half a dozen world leaders. But if you know Weissmann, he is often most impressed with some local gastronomical marvel.

And he also loves Queens, New York. “You don’t have to leave that borough to try any cuisine in the world—almost,” he opines. Quickly adding, “For the best Sri Lankan, you’ve got to go to Staten Island!”

He’s also eaten in some of the most atrocious places, but says the worst experience is a story too long to tell in one sitting. “All I can say is that the meal under the worst circumstances involves a raging storm, a muddy mountain road, a sick child, a Bhutanese knight, liver and an honorary consul. You’ll have to connect the dots yourself I’m afraid.”

What, I inquired, might be the places that have the least interesting food he’s encountered? “For least interesting, tough—I have an open mind as well as an open mouth. I guess it would be the countries where I can’t really recall the cuisine at all—they made no impression on me, or felt derivative or not deeply distinguished from better foods in neighboring countries. I recognize the fault may well be mine—I’m not picking up on what makes them special. Those countries would include Myanmar, Romania, Libya and Andorra.”

His favorite cuisine is Mexican.

These are his five most memorable meals.

My college roommate lived with a family in Cuernavaca, Mexico, for a semester. Five years after graduation, he invited me to join him for a weeklong trip through central Mexico, beginning with a visit to his Cuernavaca host family. They loved him and treated us like royalty from the moment we arrived. And to celebrate his return, they planned a special dinner.

As I walked through the kitchen, I saw the mother and two daughters grinding a mound of walnuts with mortar and pestle into a fine powder. To this they added pure cream and a touch of salt, and put this simple sauce over chile relleno (stuffed, in this instance, with cheese). Since then, I’ve had a similar dish in restaurants in Mexico, chiles en nogada, which is traditionally served around holidays. But it can’t compare. Not even close.

I’m sure its taste was enhanced by the warmth of that family’s dinner table and because it was my first true introduction to authentic Mexican cuisine. In a way, it’s similar to one’s first true appreciation for, and understanding of, art; we return again and again to museums hoping to recapture the feeling that possessed us the first time we were truly moved and excited by a painting. That exact feeling will never recur, but if you’re lucky, you’ll come close.

Since that meal, I have had incredible Mexican food prepared by some of the country’s most famous chefs, but no matter how sublime the atmosphere, presentation and taste, nothing can replace this dish and meal as my number one dining experience.

I had spent four weeks traveling through Ethiopia and while waiting for a bus in the countryside, I met an Ethiopian man who had just returned to the country after spending years on a fishing boat off the coast of Alaska. He, too, was traveling around as a tourist and heading to the same village I was. I don’t recall what was so special about this village, but what stands out in my mind was that, by the time we left it, we were both very, very hot, very, very thirsty and very, very hungry.

My new friend said we should stop at a roadside restaurant we had passed on the way there. “It’s famous,” he said.

“Restaurant” might be a bit of a stretch. It’s not unusual for some restaurants in Ethiopia to have no cutlery—food is traditionally eaten with one’s hands, using injera bread to pinch up meat, vegetables and sauces. But this restaurant also had neither tables nor chairs. Instead, we squatted in an open area around a fire as the proprietor put two freshly caught fish, their skin rubbed with a seasoning and herbs, on a grill over the fire. He handed us paper plates, and when the fish were cooked, he put them onto the plates.

As soon as the fish were cool enough to touch, my companion tore into his with his fingers, and I followed suit. It was beyond delicious. It deeply, deeply satisfied some need that I didn’t know I had. I picked it clean to the bones and asked for another. The second was as perfect as the first. I have no idea what kind of fish it was, but it doesn’t really matter—it would be impossible to replicate, even if I had a fire made from the same wood and the same type of fish rubbed with the same herbs and spices. Once again, the totality of the experience is part of what sets it apart in my memory.

This is more about drink than food. My ex-wife and I were in Sofia, Bulgaria, during the communist period. We were staying in a room that a widow rented out and she recommended a specific restaurant for a “typical Bulgarian dinner.” The restaurant looked like a brightly lit diner, and was crowded; we were seated at a booth where five men were already seated. I was put at the head of the table and my ex was offered the last free seat on the booth. The men weren’t speaking much to one another; it seemed likely they were also seated randomly.

The man next to my ex said he was an English professor, which was welcome news. He immediately offered to buy us drinks, but said that they only served vodka and Campari at that restaurant. I don’t like vodka, and my ex didn’t drink at all, so we asked for two Camparis, and as soon as mine was done, my ex discreetly switched glasses and I drank hers. Over the course of the meal, everyone at the table bought us drinks, and the Camparis were lining up in front of us. The English professor, no slouch with vodka, started speaking Bulgarian to my ex, and not in a friendly tone. “What are you saying?” I asked him. “I don’t think she’s a tourist,” he said. “I think she’s Bulgarian pretending to be a tourist.” “Don’t be ridiculous,” I said. A man directly across from the professor, who spoke some English and had introduced himself as a boxer, spoke sharply and threateningly to the professor in Bulgarian, who shut up and sulked. “I buy you drink,” the boxer said to me. The thought of a 12th Campari was more than I could bear. “Thank you, but no thank you,” I said. He frowned. “You drink, you friend,” he said loudly. “You no drink, you no friend!” There was some menace in that. “I drink,” I said, and he beamed and motioned for the waiter. An orchestra started up and the men all rose and left the booth. The boxer indicated I should go with him—I was not about to say no to him again—and he locked elbows with me on one side, the professor locked elbows on the other, and we danced, powered by Campari, vodka and, on my part, just a bit of fear. I have no recollection whatsoever of what I ate that night.

My first experience at a Michelin-star restaurant, in Paris, was not so great. It wasn’t the $40 string beans that got to me; it was a combination of brusque service and too many tables wedged into too little space. The next year, a friend, hearing that my (present) wife and I were going to Strasbourg, France, said we must make a reservation at another Michelin-star restaurant, Le Crocodile. We didn’t really have the budget for it, but decided to go, hoping they wouldn’t object if we shared a starter and an entree between us. We were seated, looked over the menu, experienced some sticker shock, but decided to really splurge and share a whole prepared truffle, the most expensive appetizer.

I explained to the waiter, in my best high school French, that we wanted one appetizer and one entree, but that we would share them. The waiter nodded, left, and returned with two truffles. I tried to explain, politely, that we had only wanted one; the waiter seemed not to understand anything but the distress in my eyes. He called the proprietress over. “Can I help you?” she asked in English. I explained the situation. “You don’t want it? We understood what you said, but we just thought you’d be happier if you each had your own truffle. We will only charge you for the one, of course.” It was, of course, beyond delicious, especially enjoyable, seasoned as it was, with kindness, generosity and understanding.

A day’s walk into the Ituri rainforest in the Republic of Congo will bring you to a Pygmy village—at least, it did in 1983. The villagers there were very welcoming, though the experience was anything but comfortable. I arrived drenched in sweat, I was anxious that my purification tablets were no match for a stagnant pond that constituted the local water supply, and the hut offered to me as accommodations was small—my feet literally stuck out the doorway—and had a rock-hard floor.And to top it off, the villagers had been gathering honey. The bees weren’t very happy about that and were swarming everywhere.

Late in the afternoon, the villagers motioned for me to follow them as they strung a long, low net in and out of some trees. We then walked about half a mile from the net, and walked back toward it again, this time with the villagers banging pots and pans. When we reached the net again, a dik-dik—the smallest of antelopes—that had been running from the banging was entangled in the net. They slit its throat and carried it back to the village, where it was cleaned and thrown into a pot, then served with the flour I had brought with me as a present. It formed into doughy clumps, and was dipped into the pot’s water after the dik-dik was taken out. As the eating wound down, the singing and dancing began: figures lit by a central fire in what is the closest to dreaming while awake as I have ever experienced.

My Five Favorite Meals features the most cherished dining experiences of bartenders, chefs, distillers and celebrities.

Interview has been condensed and edited.