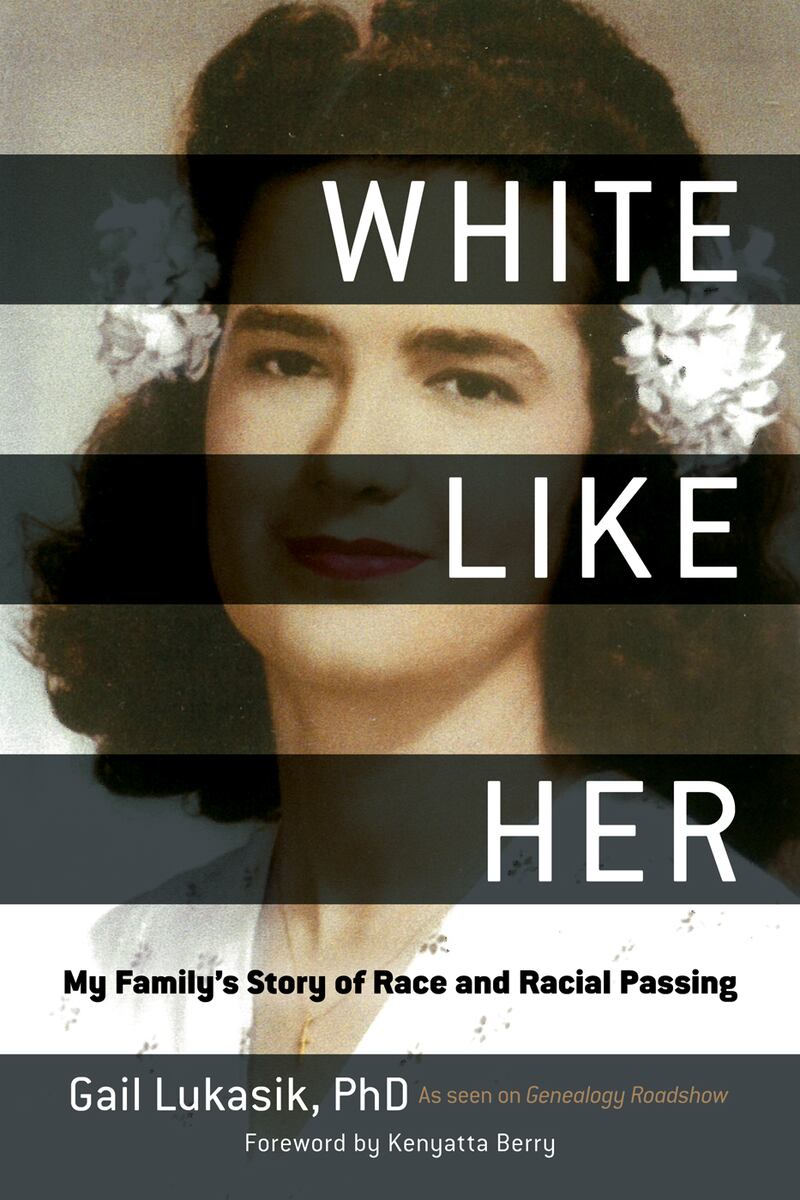

My mother leans toward the mirror. With graceful upward strokes she applies liquid foundation to her face, and begins her day as a white woman.

I perch on the edge of the blue bathtub, watching in fascination as she transforms her olive skin to a lighter shade. At 14, I have no inkling of the depth of her deception. Nor the risks she takes everyday married to my white father and living in a white, lower middle class Cleveland suburb.

It’s 1960. Seven years before the Supreme Court declares interracial marriage legal. She knows what’s at stake. Her enactment is so artful, so practiced; my father will go to his grave, thinking he married a white woman.

“Why do you wear makeup to bed?” I’m starting to question my mother’s quirky habits, starting to wonder about the blank spaces in her New Orleans family tree.

Her answer leaves me bewildered and troubled. “You never know if you’ll get sick in the night and have to be taken to the hospital. You want to look your best.”

It’ll be three decades before I understand that to my mother “best” means white. It’ll be three decades before I discover my mother passed for white.

***

There were clues I missed. Her strict avoidance of the sun, her absence of family photographs, her unwillingness to visit her family in New Orleans, and her obsession with her make-up.

Even at the end of her life, confined to an assisted-living facility, barely mobile, she continued to put on her “face” every morning. So ingrained was her fear.

If not for my curiosity about my mother’s father, Azemar Frederic, my mother would have died with her racial secret intact. In 1995, while scrolling through the 1900 Louisiana census records searching for Azemar, I made a startling discovery. Azemar and his entire family were designated black. In an instant my sense of self was shattered.

When I questioned her, she vowed me to secrecy until her death. “How will I hold my head up with my friends?” she pleaded.

I’d never seen my mother so afraid. Reluctantly, I kept her racial secret for 17 years. And in the silence of those years, I was left confused over my racial identity.

A year after my mother’s death, I appeared on PBS’ Genealogy Roadshow and revealed to 1.5 million people that my mother passed for white. On the 1940 Louisiana census my mother, Alvera Frederic, was listed as Negro, working in a teashop in New Orleans. Four years later, she moved north and married my white father. She was never classified as Negro again.

But so many questions remained. How did she accomplish this audacious act? How had she fooled my bigoted father and his entire family? Born and raised in New Orleans in mixed-race and black neighborhoods, she had no manual on whiteness, no guidebook, or a set of instructions.

Although her olive complexion and European features allowed her to slip over the color line, she must have understood that it was one thing to look white and another thing to be white. If she was to pass successfully, she had to “act” white.

***

Movies were her training ground. From the time I was six until adolescence I was her companion and escort to the Friday night double feature at the local movie house. From the movies she learned how white women dressed, styled their hair, spoke, gestured and dealt with troublesome men.

Her identification with the white women on the screen was transformative, as well as instructive, blurring the line between the real and the imaginative. For the time we sat together in the darkness she could be herself, appreciating her own performance. How she’d tricked a society intent on putting her in her racial place—a place that held her back economically, socially, and had its own inherent dangers.

Sometimes there was a theatrical daring to her passing. One Halloween for a neighborhood party she masqueraded as Marilyn Monroe, donning a platinum wig, a red satin dress with a thigh-high slit, black gloves, fishnet stockings, and a long cigarette holder that she pretended to smoke. I was transfixed by how her personality changed, how seamlessly she became another person.

Was she laughing up her sleeve? Reveling in her charade? Or was she overtly expressing her double life and the ambivalence people with mixed European and African ancestry felt? Being neither white nor black but forced into a racial category by laws, such as the one-drop rule. But these moments of “acting out” were rare.

Whether from movies or observations of white culture, my mother’s mantra was: “Manners can take you anywhere in society, even further than money.” Her insistence on manners, courteous behavior, and culture was almost manic. Being so polite, so well brought up, so cultured how could anyone doubt her whiteness.

But her passing came at a cost. Although she gained white privilege, she lost her family and her authentic self. It couldn’t have been an easy choice for her.

I’ll never know the depth of my mother’s sacrifice or the pain she felt. Though I suspect that in order to survive undetected, she must have developed a tolerance for racism, staying silent to the racial barbs she heard at work, and from friends and family. To protest might cause suspicion.

In “acting” white she became white. Wearing the mask of her whiteness, she gave me what she believed was a better life. I both appreciate what she did for me and am saddened she had to hide her true self.

I’d like to believe that passing for white is an arcane notion, no longer necessitated by racial laws, such as the one-drop rule. But in America’s racist culture, mixed-race people who can pass for white must still wrestle with this choice.

After the roadshow aired, I received an email from a woman who talked about her own experience of alienation as a mixed-race person. “Even in this time,” she wrote, “passing has its advantages.”

***

Three days after the roadshow aired, the family my mother never knew found me. I’m now part of a multi-racial family. Finally I know all my people. Finally, I know who I am—a mixed-race person. You’d never guess.

Excerpted from White Like Her: My Family’s Story of Race and Racial Passing by Gail Lukasik.