It was 1993 or 1994 when I first encountered Jean-Luc Brunel, the controversial French modeling agent, at a then-trendy South Beach restaurant called The Strand in Miami. A table near mine, set for six, expanded to seat 10, then shrank for eight, then enlarged to fit a party of 12, and was finally occupied, as I finished my meal, by a pack of extremely young women, teenagers, really, with the willowy frames and lovely faces of neophyte models, and a smaller number of older men who appeared to be… well… smug probably sums it up best.

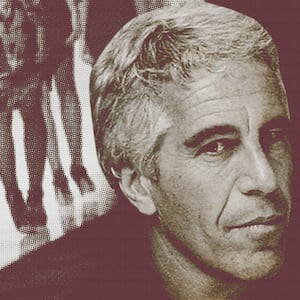

A quarter century later, I was reminded of that dinner when Brunel suddenly riveted the world’s attention in the hours immediately before the suicide of the notorious pervert pederast Jeffrey Epstein, when it was alleged that the Frenchman had provided underage women to the very freaky financier.

Shortly after that Miami night, I interviewed Brunel, among many others, for a book on the modeling industry, published in 1995 as Model: The Ugly Business of Beautiful Women. So, although I neither met nor wrote about Epstein, my phone started ringing following his latest arrest for trafficking underage women, and it hasn’t stopped since, as exposés of Brunel pile up like a mound of fetid garbage, notably in England’s Guardian, France’s Libération, the Washington Post, and The Daily Beast. And reporters have told me that, apparently, I’m among the very few journalists to have interviewed the then-elusive and now impossible-to-find Brunel.

ADVERTISEMENT

But there’s more to this story than the handful of damning quotations the papers have lifted from Model, from and about the man sometimes described as a rabbateur, i.e . one who beats the bushes during a hunt to drive game out into the open. There is the videotape of a 60 Minutes segment from 1988—long suppressed by legal order—that exposed him as an alleged serial abuser of young women, for instance; interviews with competitors who described him as a serial rapist; and a 28-page transcript of our taped interview in which I asked about the charges that Brunel was way more loco than parentis with the young women in his charge, as well as his oft-reported fondness for cocaine.

His assurances of his innocence then were barely credible, but I felt a responsibility to report them alongside the sordid charges against him, and some of the more damning passages from our conversation. But I left out what happened the same night as our daytime interview. I don’t remember why I was in the nightclub Les Bains Douches that evening—it was 25 years ago after all—but what happened there and afterward is a crystal-clear memory, most likely because I’d planned to include it in a final chapter of Model that was never written because the book was already long and tawdry enough.

My plan was to conclude the tome with a chapter on the youngest models of all, known as test board kids, discovered in malls and at modeling conventions and then thrown into the deep end of fashion’s pool—the studios and clubs of Paris and Milan—where they would either swim or sink. I’d chosen a handful of them at an annual modeling convention in New York, asked them to be my pen pals for a year, and that day at Brunel’s agency, Karin, met one of them, Robin [I’ve changed the models’ names], a Midwesterner who’d signed with him. She introduced me to her friend, who called herself Dakota, and we chatted and went our separate ways.

But there was Dakota, on the restaurant floor above the disco at Les Bains Douches, sitting with Brunel and another group of models and older men at a huge table. And when she waved hello, it was clear she was miserable. She told me she hated the place and Brunel had forced her to come. “Can you get us out of here?” she whispered, gesturing to another model. Sure, easy.

I took them in a taxi to their “model” apartment off the Champs-Elysées, a crowded room where dirty clothes covered every inch of floor and Dakota told me she’d moved there after first living with Brunel at his far more spacious and glamorous apartment nearby on Avenue Hoche. There, she’d discovered an apparent peephole that looked into the bathrooms the models in residence used, inspiring her to flee, albeit not very far. The only part of the story that wasn’t normal was that peephole. Models often bunk in their agents’ homes. “Want to see it?” Dakota asked. She still had a key.

Around the corner we went, then up one of those old French cage elevators, to a far more lavish flat, where, sure enough, there was a hidden hole drilled through a wall and a view of a bathroom. The girls were laughing about their escape when Brunel joined us. Earlier that day, he’d denied that he still used cocaine. “I had a problem,” he’d said in a staccato burst, “it was not a major. I mean, it was a problem… For four or five years I did it as fun, because I never did it in the day, and then I did it as an experiment, fine, it lasted maybe a bit longer than it should, but it had never been like a problem, it had never been—I was at work at 9 in the morning.” But, as the notes I took afterwards say, he was “uncommonly animated,” so I wouldn’t have vouched for the truth of that assertion. And he was with a friend with a case of the sniffles. And the peephole? “I want you to look behind all the mirrors,” he said. Frankly, I just wanted out of there.

A demand that Dakota return to Les Bains Douches with him made me nervous. Earlier that day, he’d struck me as shrewd, smug and vaguely sleazy. She’d told me she’d had to rebuff his advances. His reappearance added scary to that list.

There was a white Ferrari with a white leather interior sitting outside his building. Dakota sat in front and when Brunel offered to drop me off en route, I squeezed into the back. Her hand snaked around the seat where Brunel couldn’t see it. I grabbed it. She squeezed, until we reached the Pont des Arts, and I got out of the thrumming car. “Will you be okay?” I whispered to Dakota. Her voice said yes. Her eyes weren’t so sure. And off they roared into the night.

Some time later, I got a letter from Dakota. She was still in Paris—and I never learned more of what happened to her. But she reported that Robin had returned to the prairie, suffering from an ulcer. I never heard from her again, either. But what young woman, full of dreams, would want to tell the tale of how she failed as a fashion model—even if quitting was one of the smartest choices she ever made?

Over the years since, I vaguely kept tabs on the agents who were the protagonists, if not the heroes, of Model. So I heard that Brunel had broken with this and that partner and founded an agency of his own in Miami. And beginning about a decade ago, when I first learned of his friendship with Jeffrey Epstein, I certainly wasn’t surprised. For his part, Brunel and his lawyers have denied the claims that he recruited underage girls for Epstein and abused them himself. Still, he’s disappeared in the wake of Epstein’s arrest and suicide.

Now, of course, I feel for the no-longer young women who have finally been emboldened to speak out about Brunel. And I wonder—and still worry—about Dakota.