When we think of Ancient Egypt, there are a few very obvious things that immediately come to mind: pyramids, Egyptian gods and goddesses, pharaohs, and of course, mummies. Archeologists have spent centuries studying the mummification process Ancient Egyptians used to preserve the deceased, and have been utterly marveled at how well these techniques worked for a civilization that lacked the sort of modern science we take for granted today.

As it turns out, mummification was a science unto itself—and one that the Egyptians were damn good at. In a new study published in Nature on Feb. 1, a group of European scientists used new chemical techniques to study the remains of the necropolis at Saqqara, one of Egypt’s most prominent burial grounds used for thousands of years. The findings reveal that the recipe for mummification was much more ornate and complicated than we ever imagined, and made use of a host of ingredients not local to Egypt.

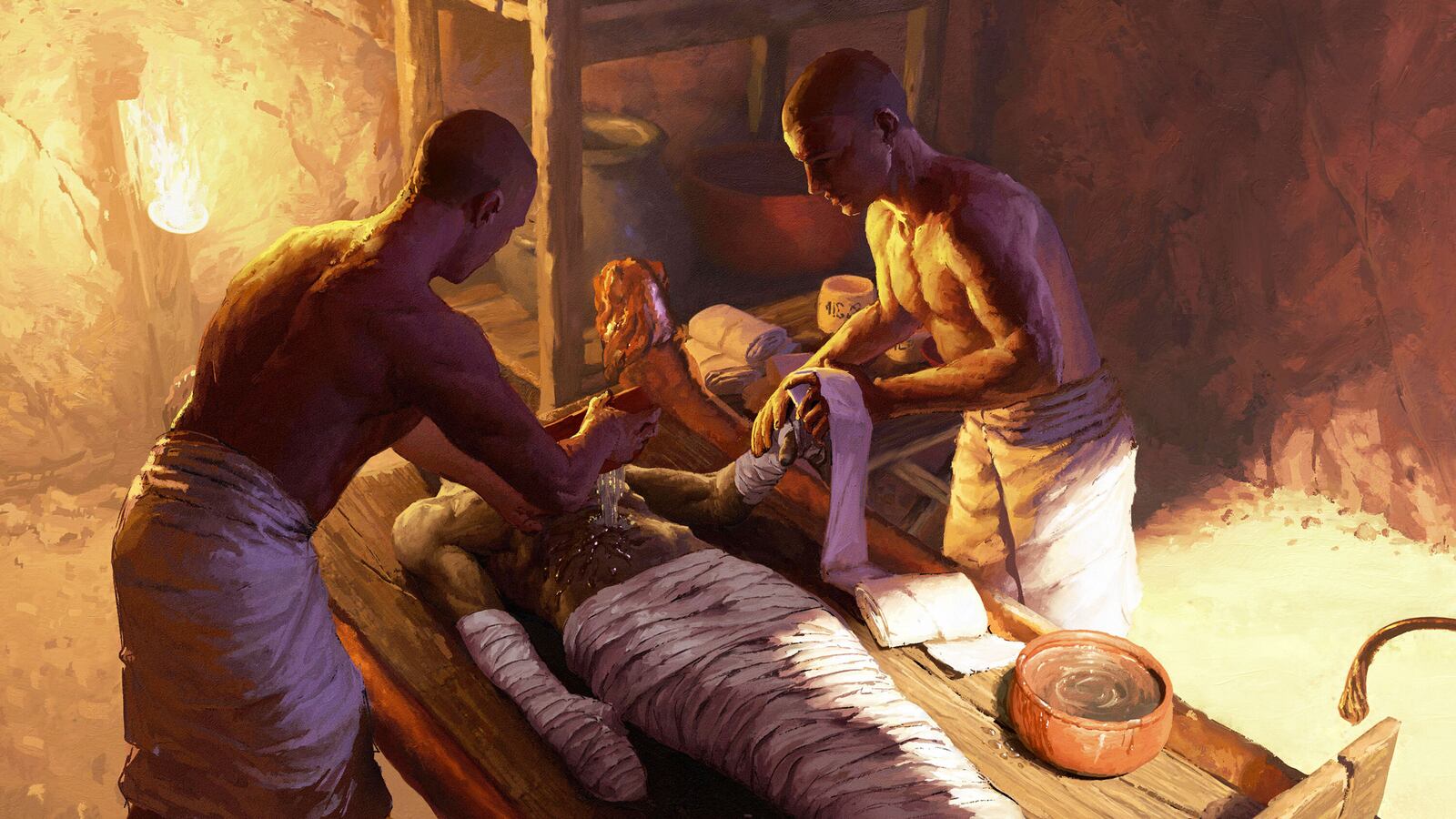

An illustration of an embalming scene with a priest in an underground chamber.

Nikola NevenovMummification has always been known to be an intricate process, involving salts to remove moisture from the body to arrest major decomposition, the removal of most major organs, and protecting the body inside and out with a spate of oils, resins, and ointments. But over time, the knowledge for how all of this was accomplished has been lost—causing researchers to focus less on the translation of ancient texts, and more on state-of-the-art laboratory investigations that can uncover the process in its original chemistry.

The new study hinges on an analysis of 31 vessels excavated from an embalming workshop at Saqqara, plus four other samples from burial chambers. The vessels date back to around 665–525 B.C. and some, miraculously, were still labeled and even had instructions for their use still preserved.

Vessels from the embalming workshop at Saqqara.

M. Abdelghaffar“We have known the names of many of these embalming ingredients since ancient Egyptian writings were deciphered,” Susanne Beck from the University of Tübingen in Germany, who is leading the excavation, said in a press release. “But until now, we could only guess at what substances were behind each name.”

Improved biochemical techniques from the last few years have allowed the team to study the molecular residue left over from the vessels. They found an incredible array of ingredients: oils and resins from many kinds of trees and plants, animal fats, beeswax, and more. But there were also quite a few surprising revelations.

The Saqqara Saite Tombs Project excavation area.

Susanne BeckOne of the vessels, for instance, was labeled as antiu, which has historically been translated as myrrh or frankincense. But the new study shows that antiu is actually a blend of many different ingredients, including cedar oil, juniper oil, and some animal fats.

Other revelations included a better understanding of exactly what ingredients were used for embalming what specific body parts. It turns out, pistachio resin and castor oil are only for the head.

Lastly, the biggest overall lesson was that many of the substances critical for embalming don’t even come from Egypt. The team found traces of elemi resin—which had to be brought in from tropical Asia and Southeast Asia. Another substance, dammar gum, is produced by the dammar tree—which has never been brought to Egypt and only grows in Southeast Asia. According to researchers, it’s a sign of how Egyptian mummification helped to fortify a much more extant network of trade between Egypt and other regions across the globe.