Among her first phone calls were her husband (“Sweetie, we won.”) and Vicki Kennedy, Sen. Ted Kennedy’s widow, telling her, “Now Teddy can rest.”

Ted Kennedy had long been the inspiration for health care as a right, not a privilege, calling it “the cause of my life,” and Nancy Pelosi, in her role as the first woman speaker of the House, had made it happen. Rushing to a hastily called meeting of her caucus shortly after the Supreme Court announced its decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act, Pelosi encountered California Rep. George Miller, one of her staunchest allies. “What a great victory!” she said. “You bet your ass (it is)” he said. “I did,” she replied, as they both laughed.

Pelosi put everything on the line to push for passage of the ACA. She had confronted Rahm Emanuel, then the White House chief of staff, who was urging President Obama to adopt a scaled-back version that would cover only children. She dubbed it “Kiddie Care,” likening it to the “eensy, weensy spider, teeny tiny,” a legislative effort so small it wasn’t worth her bother. Emanuel told the Chicago Tribune after the vote that he had advised the president about the political cost of doing this. “And thank God for the country, he didn’t listen to me.”

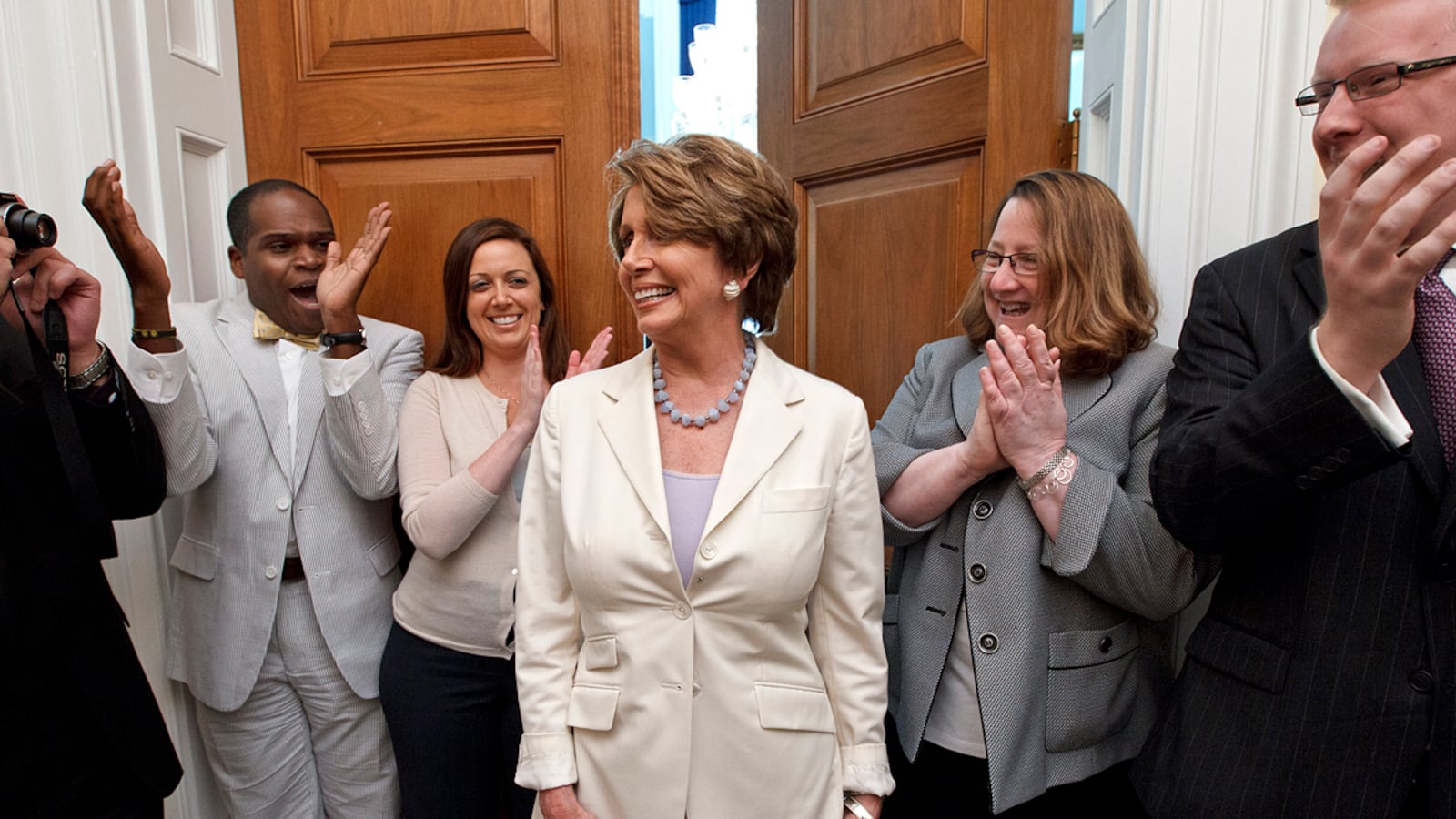

On decision day last week, Pelosi wore her lucky purple pumps, the same ones she had on when the ACA passed on March 21, 2010. When Obama called, she held the receiver up so he could hear the cheers from the Democratic Caucus. She and her staff later celebrated with brownie bites and cake from Costco (not paid for at taxpayer expense, an aide points out). The festivities were a far cry from the reception she received after the 2010 election, when 52 Democrats lost their seats, many blaming the unpopular health-care bill, and by implication, their leader, for browbeating them into voting for the legislation.

“The politics be damned, this is about what we came to do,” she said at a news conference following the high-court decision. “And any time we want to waste time seeing it through a prism of what does this mean in terms of the election, we undermine our purpose in coming here and acting upon our beliefs. We are very, very excited about this day. It is historic. It ranks right up there when they passed Social Security and Medicare, and now being upheld by five justices of the Supreme Court.”

Pelosi never voiced any regrets about her single-minded focus on getting the health-care bill, and it’s doubtful she had any. As with FDR, one of her political heroes, the opposition she faced along with the demonization in the last election is proof-positive that she did the right thing. And lots of other Democrats seem to feel the same way, even those who were burned by their backing for the bill. When Politico went back in the wake of the SCOTUS decision to interview a dozen of the 2010 losers, they found “virtually no second-guessing and hardly any regrets.”

Taking on the famously prickly and punitive White House chief of staff was just one of many battles Pelosi fought to get the ACA across the finish line. She pushed back on the liberals in her caucus when they said the bill was worthless without a public option. ”She said no, this is fundamental change, this is historic, this is the last thread to weave into the social safety net,” recalls Matt Bennett, of the centrist Democratic group, Third Way.

As the perceived standard-bearer for the left on Capitol Hill, Pelosi giving support to the bill was essential to hold down defections. At the same time, when a group of pro-life Democrats threatened to scuttle the measure over the abortion issue, the compromises she made held up in part because of her own strong Catholic beliefs, and the trust that the various factions placed in her judgment.

What’s next for Pelosi? If the Democrats succeed in winning back the majority in November, she would likely reclaim the speaker’s chair. That would put her side by side in the history books with the legendary Sam Rayburn, who twice was moved aside as speaker when the Republicans controlled the House for short periods.

Pelosi recently marked her 25th anniversary in Congress. Now 72, she says she has been graced with great genes and is experiencing no lessening in her energy. She is popular within the Democratic caucus, and there is no apparent Machiavellian maneuvering to unseat her. A tireless fundraiser, she has raised $50 million for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and various candidates.

If the Democrats fall short in retaking the majority, reupping as leader may be less appealing. “It’s no power and lots of responsibility,” says a friend. Pelosi was asked at a recent roundtable with a small group of reporters, “What is left here for you ... What do you still want to accomplish?”

Plenty, it seems. Pelosi wants more women in Congress, and affordable, quality child care. She calls it “the missing link,” noting that women running for Congress are still being asked, “Who’s taking care of your children?” Another sweeping social program is probably not achievable, at least in the short term. Still, Pelosi dares to dream, and sometimes dreams come true.