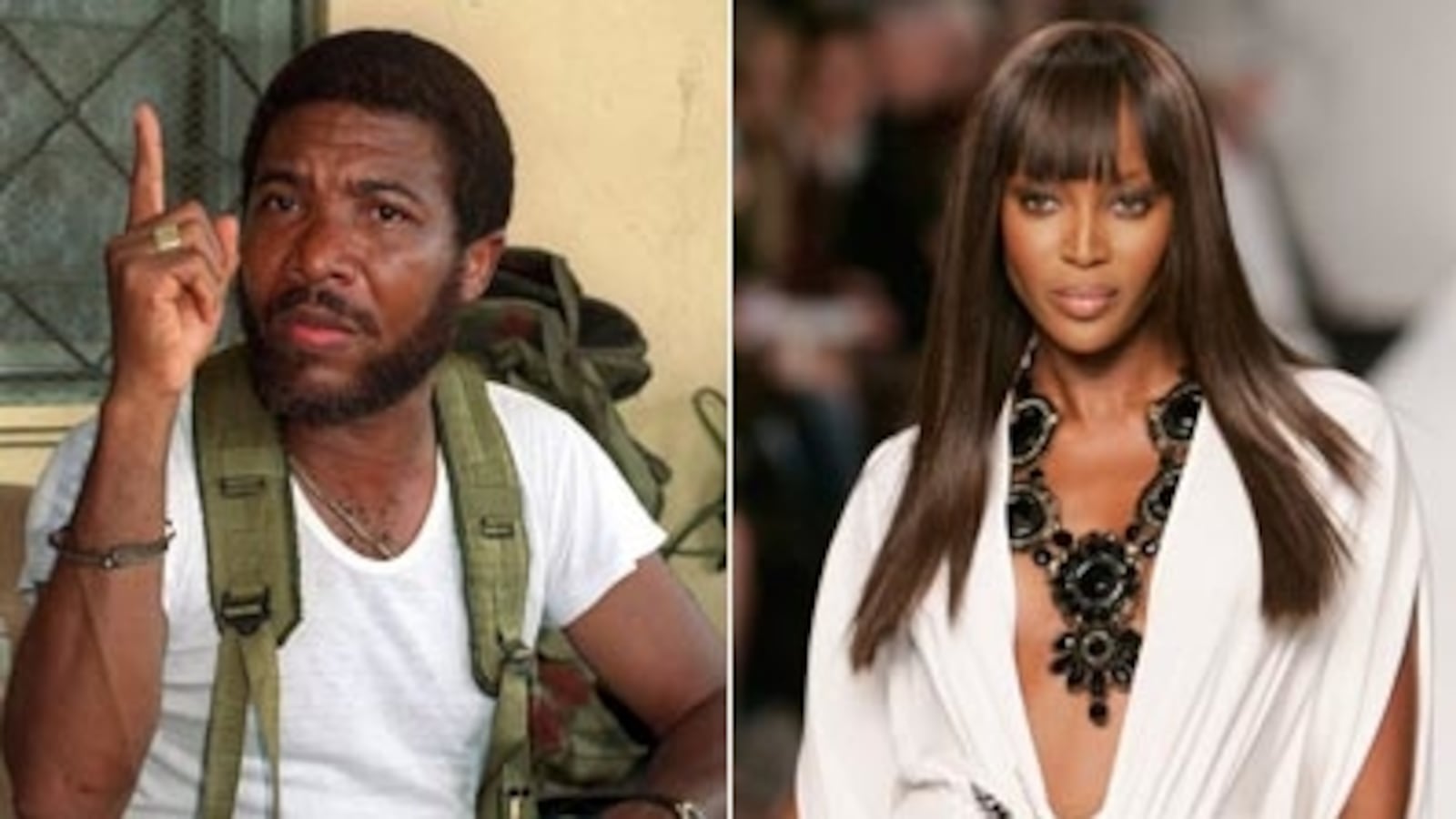

With an international war crimes tribunal's July 1 call for model Naomi Campbell to testify at the trial of former Liberian dictator Charles Taylor this month, this might be a good moment for the people of Sierra Leone to thank her. Yes, they should thank Naomi Campbell—for her high-profile non-cooperation with the court.

Click Image Below to View Our Rankings of Celebrities' Charitable Impacts

How is that? People often note, sometimes with disdain, that celebrities bring their fame to bear on issues of importance to society. It turns out that even their unethical, ornery, or otherwise awful behavior can do that just as effectively. In Campbell's case, refusing to clearly answer an ABC News journalist's basic questions about whether she received a blood diamond from the Liberian dictator 13 years ago (to say nothing of smacking a television camera as she left the interview in a huff) was just one attention-grabbing example. (There have been others, and I will get to them in a moment.)

In a sense, the Sierra Leone tribunal needed a mercurial “supermodel.” The sad fact is this: The court that is trying Taylor in the Hague (as well as a small number of “big fish” in Sierra Leone) has toiled in relative obscurity since it issued 13 indictments in 2003. Truth be told, courts investigating crimes against humanity tend to garner surprisingly little popular attention just one decade into the 21st century. Through her parsed denials, incomprehensible unwillingness to fully support the work of the tribunal, and other actions (or inaction), Campbell is helping to draw attention to the blood-diamond-fueled horrors committed in Sierra Leone.

In April, Naomi Campbell snapped at ABC News for asking about the diamonds.

When I reported from the country in 2003, soon after the atrocity-filled civil war ended, I interviewed teary-eyed teenagers about young fighters who hacked limbs off civilians to terrorize their neighbors and about a rebel takeover of the capital that left so many corpses in the streets that dogs feasted on them for days. I also tried to figure out how those kids, or anyone, could possibly overcome such trauma. The need for attention to such things remains very real.

Let’s all remember that the most important part isn’t about the model; it is about justice.

In January, it emerged that Campbell had refused to cooperate with the war-crimes tribunal (which court officials have since confirmed to The Daily Beast), despite the protestations of her publicist. Then came the strange knock-the-camera-over interview in the spring, which brought mention of the tribunal to the nightly news and spread it across the Internet.

Even Campbell's silence spoke volumes. In the ABC News report, actress Mia Farrow says that Campbell said, at a breakfast in South Africa in 1997, that she received a diamond gift from Taylor's men the night before. Campbell's former agent recently confirmed that, clarifying that the model was actually given a half-dozen precious stones that she saw. Campbell hasn't offered a response. Strangely, her actions (and inaction) may already add up to the greatest public service of Campbell's career: raising awareness about the conflict diamond-fueled hell that touched down in Sierra Leone.

But Campbell now has an opportunity to take her morally indefensible lack of cooperation with the court much further. If she actually shows up, as called, to testify on July 29 about her interactions with the former Liberian dictator, her presence would be media catnip. And if Campbell doesn’t appear—risking up to seven years in prison, according to a court document made public this week—the surreal sideshow could bring even more attention to the Taylor trial. (Suggested possible headline: Supermodel Risks Jail for War Criminal.)

Why do international trials of suspected war criminals need the world's attention? The ideal behind such trials goes beyond justice being served in a single case; they are, ideally, about creating a deterrent and restoring the meaning of justice in countries where it has been shattered. They also aim to show other warlords, dictators, government ministers or even elected officials what could happen to them if they order or allow atrocities.

How important is the Naomi Campbell-blood diamond anecdote to the prosecution's case? It does suggest that the Liberian dictator “had access to enough raw diamonds from the fields of [neighboring] Sierra Leone to give one to a woman he hardly knew.” Taylor has claimed, in court, that he has never had anything to do with any conflict diamonds, while the prosecution insists that Taylor was in South Africa in 1997 to trade the stones for weapons to strengthen his allies’ grip on Sierra Leone's diamond fields when his men gave Campbell the precious gift. But in reality, as a lawyer well versed in Taylor's case told The Daily Beast, Naomi Campbell's testimony isn't "material" to the prosecution's case.

Now Campbell may not wait until her July 29 date with the tribunal to help justice to shine. Given her famously volatile history (when faced with services that she doesn't believe are up to snuff or when asked questions she doesn't appreciate), could the delivery of the subpoena trigger some media-friendly fireworks? Will she or won't she agree to testify? Whatever happens, let's all remember that the most important part isn't about the model; it is about justice.

If she plays her cards right (or wrong, depending on your perspective), she might do a better job of promoting the proceedings than any prominent advertising company on Madison Avenue could. Of course, the tribunal might have had to use some of Charles Taylor's long-sought diamond revenue to hire such professionals, and that wasn't possible. However quixotically, Campbell is already effectively fulfilling their role—and she may have been compensated in advance by the same source.

Eric Pape has reported on Europe and the Mediterranean region for Newsweek magazine since 2003. He is co-author of the graphic novel Shake Girl, which was inspired by one of his articles. He is based in Paris. Follow him at twitter.com/ericpape