KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—The American space program roared to new heights in the wee hours Wednesday morning with a trajectory it abandoned a half century ago: returning to the moon.

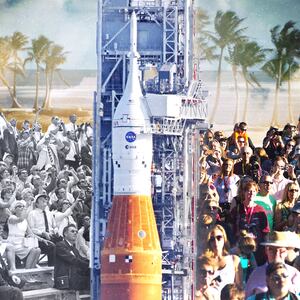

After a decade of delays, cost overruns, and redesigns, NASA’s Artemis 1 blasted off from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center at 1:47 a.m. local time, with all the dramatic flourish nearly 9 million pounds of thrust can promise. Thousands of late-night viewers watched the biggest rocket NASA has ever built ascend in a stunning spectacle of fire against the dark sky, despite a slight delay. The launch was initially expected at 1:04 a.m.

“For once I might be speechless,” Artemis I launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, the first woman in history to oversee a NASA countdown and liftoff, said to the NASA team afterward.

“We have worked hard as a team... this is your moment.”

Blackwell-Thompson said the launch was “the first step in returning our country on the moon and on to Mars,” and thanked her team for the successful launch. “What you have done today will inspire generations to come, so thank you for your resilience.”

The celebrated launch, however, surrounds concerns about the safety of the overall Artemis project, and doubts about whether its stratospheric costs—$4.1 billion for this mission—can be justified over the next few decades. The liftoff served as a redemptive moment for the brand new moon-to-Mars program, following four postponed attempts after a hydrogen leak, an engine coolant problem, and two Florida hurricanes.

This was no ordinary rocket launch. Some space experts call it an extraordinary achievement that sets the stage for putting boots on the moon by 2025 or 2026 and ushering in a new era of exploration beyond Earth’s orbit. Others call it a grossly overpriced piece of political pork.

NASA insists that “space is hard’’ and unforeseen problems will challenge any ambitious agenda. The key is not to give in, Gregory R. Wiseman, NASA’s chief astronaut, said at an October press conference at Kennedy Space Center: “This is a reflection and continuation of the Apollo program and its generation. Apollo was about doing, and that’s what Artemis is all about: doing. It’s what inspires people.’’

Wiseman may have a point. Inspiration runs deep in the sight of seeing a rocket taller than the Statue of Liberty and weighing nearly 6 million pounds rise from historic Pad 39B and arc majestically over the Atlantic Ocean after takeoff.

The controlled explosion of orange flame and white smoke enveloped the Space Launch System (SLS), the most powerful rocket system in the world. Sitting atop was the Orion deep space vehicle, which is expected to carry NASA astronauts to the moon and back with the Artemis 2 and 3 missions.

The four RS-25 engines—refurbished from 21 previous Space Shuttle flights—expended 720,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid hydrogen and oxygen as fuel in order to pull off the eight-minute ride to escape Earth’s gravity. After orbiting the planet, a crewless Orion separated from SLS and began its 240,000-mile journey to circle the moon, in all using 55 engines and motors on its roundtrip venture. The spacecraft will come home in eight weeks with a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

The dramatic start of the Artemis 1 mission may have temporarily swept aside the problems that have plagued the SLS since its inception in 2010, but they will continue to be addressed. These concerns stem from the transfer and storage of cryogenic liquid hydrogen, which must be kept at minus 420 degrees Fahrenheit. Adding to the complexity, hydrogen is the lightest and smallest atom on the Periodic Table, so it can find its way into the tiniest spaces inside the SLS–creating a potentially dangerous leak.

Will such issues, along with the enormous costs, ultimately make the Artemis program unsustainable?

“It’s a simple question with a complex answer,’’ John Logsdon, a professor emeritus of space policy at George Washington University, told The Daily Beast. “On the plan that NASA has in place, I think the first round of lunar missions is sustainable. But it’s an interim step to long-term activity on the moon, which will require a far less expensive transportation system.’’

The Artemis 1 moon rocket and the Orion spacecraft at Kennedy Space Center on November 15, 2022.

Red Huber / Getty ImagesOthers say what is or isn’t sustainable is a matter of context.

“The F-35 (stealth jet fighter) project is at $1.7 trillion, from an original $200 billion budget,’’ Greg Autry, a space policy and business expert at Arizona State University, told The Daily Beast. The Government Accountability Office routinely reports that Medicare fraud waste and abuse is $40 billion to $80 billion. Are Medicare and the F-35 ‘sustainable?’”

The last time America sent a spacecraft to the moon and safely returned it to Earth was in 1972, when Apollo 17 ferried the last three humans to visit Earth’s neighbor, with Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt actually setting foot on its surface. That was 50 years ago, and memories of such feats are short-lived, said Casey Dreier, senior space policy adviser for the Planetary Society.

“The idea of going back to the moon has almost receded into myth because most people were born after Apollo,’’ he told The Daily Beast. “This effort is happening in the background for a lot of people and the awareness is pretty low. But I also think there’s a thirst in the nation right now to be part of something bigger than yourself, and that contributes to our ability to do important things and expand ourselves as humans.’’

Testing, Testing, Testing

NASA engineers have spent years going over every inch of the Artemis 1 system, most of which is new and unproven in a hostile environment. Crews worked three shifts a day, seven days a week to get the craft ready for today’s launch. The original date was set for December 2016, but nearly 20 technical delays kept halting the timeline. The complexities were, and still are, enormous, said Tom Whitmeyer, deputy associate administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Development.

“This is the most instrumented vehicle ever to fly into space, with thousands and thousands of instruments,’’ he told reporters in August. “And there are a lot of additional instruments that we normally wouldn’t fly, a lot of new flight hardware and software.’’

That means working out potential bugs that can’t be tolerated when NASA ferries astronauts to the moon aboard Artemis 2 and 3 in the near future, said mission manager Mike Sarafin: “That’s why it’s important to get this first flight right, because it enables everything that happens afterward. Nobody will remember a successful mission, but everybody will remember an unsuccessful one.’’

The core stage for the first flight of NASA’s Space Launch System rocket is seen in the B-2 Test Stand during a hot fire test Jan. 16, 2021, at NASA’s Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi.

NASA TVVirtually all the data retrieved from Artemis will be used to update procedures, software, hardware, and even decision making for the next ventures. Although people aren’t aboard Artemis 1, two doppelgangers are: Mannequins named Helga and Zohar are sitting in Orion’s cockpit, wearing 5,600 sensors and a special skin to analyze the effects of radiation far from Earth’s protective atmosphere.

“In a nutshell, this mission is all about validating how things work,’’ said Debbie Korth, Orion program deputy manager. “We expect to learn a whole lot.’’

Such a wealth of information will be invaluable to NASA. But any glitch or ill-timed event—such as the misfiring of a thrust rocket to reposition the craft—could render it all moot, said Rick LaBrode, flight director lead for Artemis.

“This mission is 42 days, and at one point we’ll be about 60 miles above the surface of the moon, and it's going to be spectacular,’’ he said. “But if we don't get the return [to Earth] burn correct, we lose the capsule.''

It Costs How Much??

If people aren’t familiar with this new lunar effort, they probably aren’t aware of the controversial price tag that comes with it. Artemis originally was to be four missions at $500 million each, but those estimates were made a decade ago. The financial picture has changed since then.

A 2021 NASA Office Inspector General (OIG) audit adjusted the cost of each mission to $4.1 billion, a number that was deemed “unsustainable.’’ This brings the expected total cost of Artemis from its inception to 2025 to $93 billion.

“NASA lacks a comprehensive and accurate cost estimate that accounts for all Artemis program costs,’’ the OIG report noted. “For fiscal years 2021 through 2025, the Agency uses a rough estimate for the first three missions that excludes $25 billion for key activities related to planned missions beyond Artemis 3.’’

To drive down costs through competitive bidding, NASA is required to review multiple proposals on any job. This wasn’t always the case with Artemis, according to the report.

After receiving $2.5 billion less in federal money for its future lander that will actually ferry astronauts from lunar orbit to the moon’s surface, the agency scrambled, and selected a single contractor—SpaceX, for its Starship vehicle—“rather than two as the Program preferred,’’ the OIG noted. Jeff Bezos, the head of rival space company Blue Origin, furiously protested the decision—and lost.

Meanwhile, rocket technologies like SLS are quickly becoming outdated thanks to the advent of reusable—and vastly less expensive—boosters being developed by SpaceX, Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, and many other private companies.

This “competition’’ begs the question about the sustainability of the Artemis program, Laura Forczyk, a private space consultant in Atlanta, told The Daily Beast.

“Financially, it may become unsustainable over time, especially if less expensive alternatives such as SpaceX’s Starship begin to prove they are capable of the same kind of lunar missions,’’ she said.

It may be that future Artemis missions take advantage of less expensive commercial hardware and services. However, Congress will still desire to direct NASA funding to key states and districts, so in some cases, “the expense of the program is a feature, not a bug,’’ added Forczyk.

Artemis has generated more than $20 billion in total economic output and supported more than 93,700 jobs nationwide, according to the agency’s Economic Impact Report from October 2022. The districts benefiting from this economic influx can be found in all 50 states. But while the big prime contractors, such as Lockheed Martin, can rely on the deep pockets of Department of Defense contracts, the smaller startups, such as the lunar payload service providers, would be hit hard.

“They would feel the impact if Artemis were to be canceled,’’ Forczyk said. “Some of them might not survive without those government (NASA) contracts.’’

Money and politics aside, one reason for the hefty price of Artemis is that astronauts will require extensive redundancies in safety and life support systems. This is why some critics argue the merits of sending people into space when cheaper, faster and more efficient robots can do the job.

A probe on the moon or Mars, for instance, can operate for years using solar panels for power, and never worry about where its next meal is coming from—much less how to get back home.

In their new book The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration, astronomers Martin Rees and Donald Goldsmith question the Artemis project’s costs in relation to less expensive alternatives.

“While human hearts understandably lie with human exploration, robots offer the chance to explore the closest objects in the solar system more safely, more effectively and far more cheaply that astronauts can,’’ the authors say. “Robotic exploration also costs money. But compare the $9.7 billion that NASA spent over 24 years to create the Webb Telescope with the $93 billion that NASA plans to spend on developing Artemis through 2025.’’

The authors add that the “the real question is how much we really need astronauts to visit other worlds, as opposed to just wanting them to do so.’’

The public has its opinion too, according to a Pew Research Center study, which said 63 percent of respondents want to make the planet’s climate system a NASA priority. Going back to the moon ranked low at 13 percent, and sending people to Mars weighed in at 18 percent.

Inspiring a New Generation

NASA has always been the target of critics, in part because of how its budget—$24 billion for 2022—is divided among its 10 main field centers and thousands of contractors in all 50 states. And because many projects stretch over subsequent presidential administrations, keeping them alive under the fire of budget cuts is one of the agency’s biggest headaches. The team that worked on the Galileo probe to Jupiter, for instance, managed to keep the program alive over three decades.

But as Galileo, the Mars rovers, and Hubble and Webb Space Telescopes prove, the “return on investment’’ is about discovery, not money, argued Dreier of the Planetary Society.

“The goal is more expansive than putting someone on the moon and getting them back safely,’’ he said. “Artemis accords (22 nations) are being signed across the world, indicating a broad global interest in lunar exploration and cooperation in a way we haven't seen before.

“The ultimate goal is creating and sustaining a lunar economy and presence and expanding those capabilities over decades. It’s like Ernest Shackleton exploring the South Pole, and now we have permanent camps there.’’

If Artemis inspires a new generation to make a difference, to tackle the improbable, it will be worth it, said Lynda Weatherman, president of the Economic Development Commission, in Rockledge, FL., an organization that promotes space-related business.

“We all know this is an expensive endeavor, but the U.S. is embracing space as part of who we are,’’ she told The Daily Beast. “People on the street and scientists both will say the same thing. How do you explain to someone that the return on investment will be worth it in the future? I don’t know, but I believe it will.’’