Three is a trend. And we have a distinct trend of 21st century, ultra-modern, transmission-and-distribution-and-exchange systems inexplicably crashing.

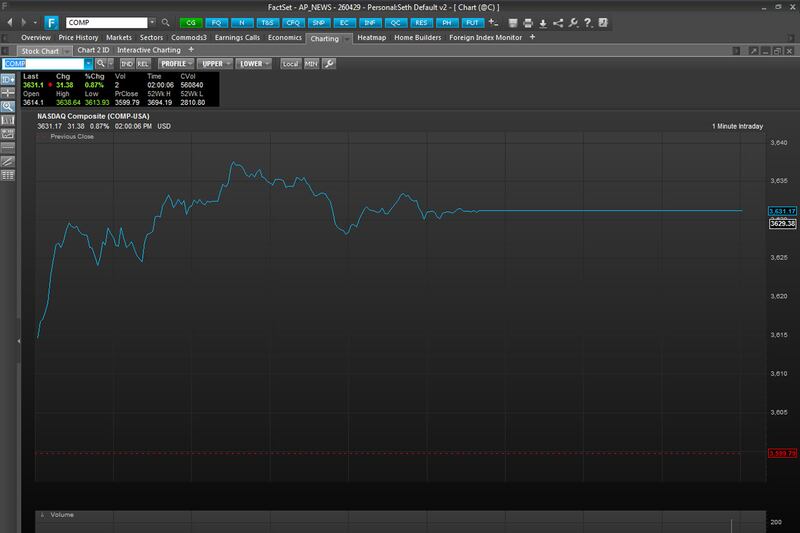

On Thursday, it was NASDAQ. The (irony watch!) electronic exchange, where technology stocks like Intel, Microsoft, and Apple are traded, simply went down at about 12:15 p.m., and stayed offline for about three hours. The parent company was generally silent. To look at the its website, you’d have no idea anything happened.

Last Friday, Google went down for about five minutes, momentarily reducing internet traffic by 40 percent. On Monday, e-commerce giant Amazon.com was down for about 25 minutes, costing the retailer millions of dollars in sales. Last Sunday night, for no particular reason, Cablevision had widespread outages of cable and internet service in Fairfield County, Connecticut. Earlier this month, The New York Times’s website went dark for a few hours.

Now, websites crash all the time when they get a sudden burst of traffic. Today, Reddit.com, which bills itself as the internet’s front page, came to a standstill when libertarian hero Ron Paul signed on to do an AMA.

But these large-scale outages at massive websites are scary because they’re unpredictable, and because they’re largely unexplained by external stresses. Take NASDAQ. Thursday was a low volume trading day on Wall Street. Most investors are on vacation. There was no big news event or major initial public offering. No, a technologically advanced electronic exchange, on which hundreds of billions of dollars of transactions are sealed daily, simply stopped work for about half the trading day. And it was similar for the other big outages at Amazon.com, Google, or Twitter. In these instances, the companies didn’t point to a surge in orders, or a sudden burst of searches for cute kittens, or a tsunami of snarky 140-character missives. They just went out--and then came back on.

But we don’t expect the industrial ones, the giant ones, the ones that contain entire economic ecosystems to fail. For these companies, it’s not like the website or the communications network is a tool, or a subsidiary. It’s the whole business. Without its accessible, hyper-functioning electronic exchanges, there is no NASDAQ. The stakes are so great that you would think the people who own and run them would invest heavily in redundancy. Actually, you’d expect that they would invest in Prepper, paranoid, fantasy-levels of redundancy. If your organization’s reason for being is to provide a communication channel (and NASADQ, as much as Google or Twitter, is a communications channel), then it would behoove you to have one or two alternate systems that can be turned on the minute things go wrong.

These events are also unnerving because you can’t point to and see a particular physical place where there is a problem. When roads aren’t working, we understand that it is because of that disabled car by Exit 37. We know that a transformer fire often leads to a power outage. These companies all have physical footprints--offices, headquarters buildings, warehouses and the like. Nasdaq has a trading site in the middle of Times Square, which is largely a television studio. But they generally conduct their business elsewhere--in the cloud, in cyberspace, in server farms, in fiber-optic cables. Anywhere and everywhere. The result is that when something goes wrong, it’s not always clear to the powers that be what the problem is and when it will be resolved.

There’s a great irony. We recently observed the 10-year anniversary of the insane, highly troubling blackout of 2003, in which a huge chunk of the U.S. experienced a loss of power. This summer, with heat waves all over the country, observers expected a repeat. After all, there’s been a big deficit in the investment needed to modernize our infrastructure. But this summer, the 19th and 20th century electric distribution and transmission infrastructure held up quite well--in part because of innovations like demand response.

It turns out it is the 21st century commercial networks that are more susceptible to disruption.