Over a 1,000 light-years away from Earth, astronomers believed there lurked two stars orbiting a black hole in a system called HR 6819. Discovery of this neighboring black hole made the headlines in 2020, but a strong contingent of scientists were dubious about the claims being made.

Rather than arguing with each other back and forth, the original team behind the HR 6819 discovery joined forces with the skeptics. The supergroup astronomy team has now uncovered the truth behind the mysterious cosmic entity: There’s no black hole in the star system, but there is something called “stellar vampire,” an even rarer and more exciting phenomenon.

Back in 2020, astronomers at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile noticed curious radio-light signals being emitted from HR 6819, a known binary star system. One star seemed to orbit an unseen celestial body every 40 days, while the other star exhibited an inexplicably wide orbit. The ESO researchers were convinced the unseen body was likely a black hole, making HR 6819 not binary but a triple star system instead.

ADVERTISEMENT

That same year, another team of researchers led by Belgium astronomers at KU Leuven proposed the opposite: there was no black hole. The unusual movements astronomers were seeing was likely due to one star gaining mass by feeding off its fellow orbiting star.

Fast-forward to 2022: In a new study published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics on Tuesday, the ESO-KU Leuven team confirmed this rarely seen phenomenon using sharper data obtained with ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) instrument and Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI).

Using the combined strength of two telescopes, the team was able to pick out two separate light sources contributing to make one beam of light. This finding suggested the two stars were much closer to each other than if a black hole was separating them. “These data proved to be the final piece of the puzzle, and allowed us to conclude that HR 6819 is a binary system with no black hole,” KU Leuven researcher and study co-author Abigail Frost said in a press release.

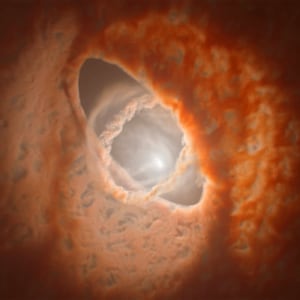

But this closeness points to something a bit more insidious: stellar vampirism, where one star saps the atmosphere of its companion star. The vampire of the pair ends up gaining more mass and is able to spin much more rapidly. In the end, there was no black hole, but there was a ravenous star bent on sucking up the life force of its partner.

Astronomers say it’s difficult to catch stellar vampirism in action since it’s a short-lived phenomenon, but these findings may prove useful to understanding the evolution of massive stars, and the formation and behavior of associated phenomena like gravitational waves and violent supernova explosions. Insights into these processes ultimately help give scientists a better picture of how the entire universe formed and how it continues to change over time.

The ESO-Leuven team plans to continue monitoring HR 6819 to follow its lifecycle and learn more about binary systems. They haven’t given up yet on finding stellar black holes, which are a bit of an elusive species. But as astronomers estimate there may be 40 quintillion black holes hiding in the dark recesses of space, one is most certain to turn up.