As the case of Aimee Copeland entered national consciousness this week, we’ve had occasion to learn about the horrors of necrotizing fasciitis, the body-ravaging infection that’s often referred to as flesh-eating disease.

Copeland, a 24-year-old graduate student in Georgia, contracted the infection two weeks ago, when she fell from a zip line into a river of brackish water and gashed open her leg, providing a deep enough wound for bacteria in the water to enter and penetrate below her skin.

She now finds herself in a hospital bed, a respiratory tube down her throat, one leg amputated, and more amputations likely to come, including of her fingers and her remaining foot, the Atlanta Journal Constitution reports.

The harrowing experience of necrotizing fasciitis is incomprehensible to those who’ve not gone through it.

The exact prevalence rate is unknown, but it’s rare enough, says William Schaffner, chair of preventable diseases at Vanderbilt, that it is not considered a “reportable” disease. Estimates vary state to state.

And, in part, it’s the very rarity of the diagnosis—as well as its extreme and rapid progression—that leaves survivors bewildered long after the ordeal is over.

“I’m walking around and unless I take my shirt off and you see the scar, you have no idea that I’ve gone through this,” says Sean Helgesen, who contracted necrotizing fasciitis four years ago. “Whereas there are people whose lives are compromised because of the disease and when you think about it, I got off pretty easy. That was tough to think about it.”

Helgesen, now 43, was a physical education teacher at a high school in California. During a routine workout, he pulled a muscle on the right side of his torso. The muscle soreness soon escalated into a storm of extreme symptoms—crippling pain, flu-like weakness, unquenchable thirst. In a few days he was unable to lift his right arm. At last, he agreed to go to the emergency room, where, he says, doctors told him his organs were in the process of shutting down.

“They told my wife that I had a 20 to 25 percent chance of making it,” he said.

It was his great fortune, Helgesen said, to encounter Dr. Lawrence McArthy, who was familiar with necrotizing fasciitis and rushed Helgesen into surgery within two hours of his checking into the hospital. When he emerged, he had a massive amount of flesh missing from the right side of his torso, a swath cut from his armpit down to his hip.

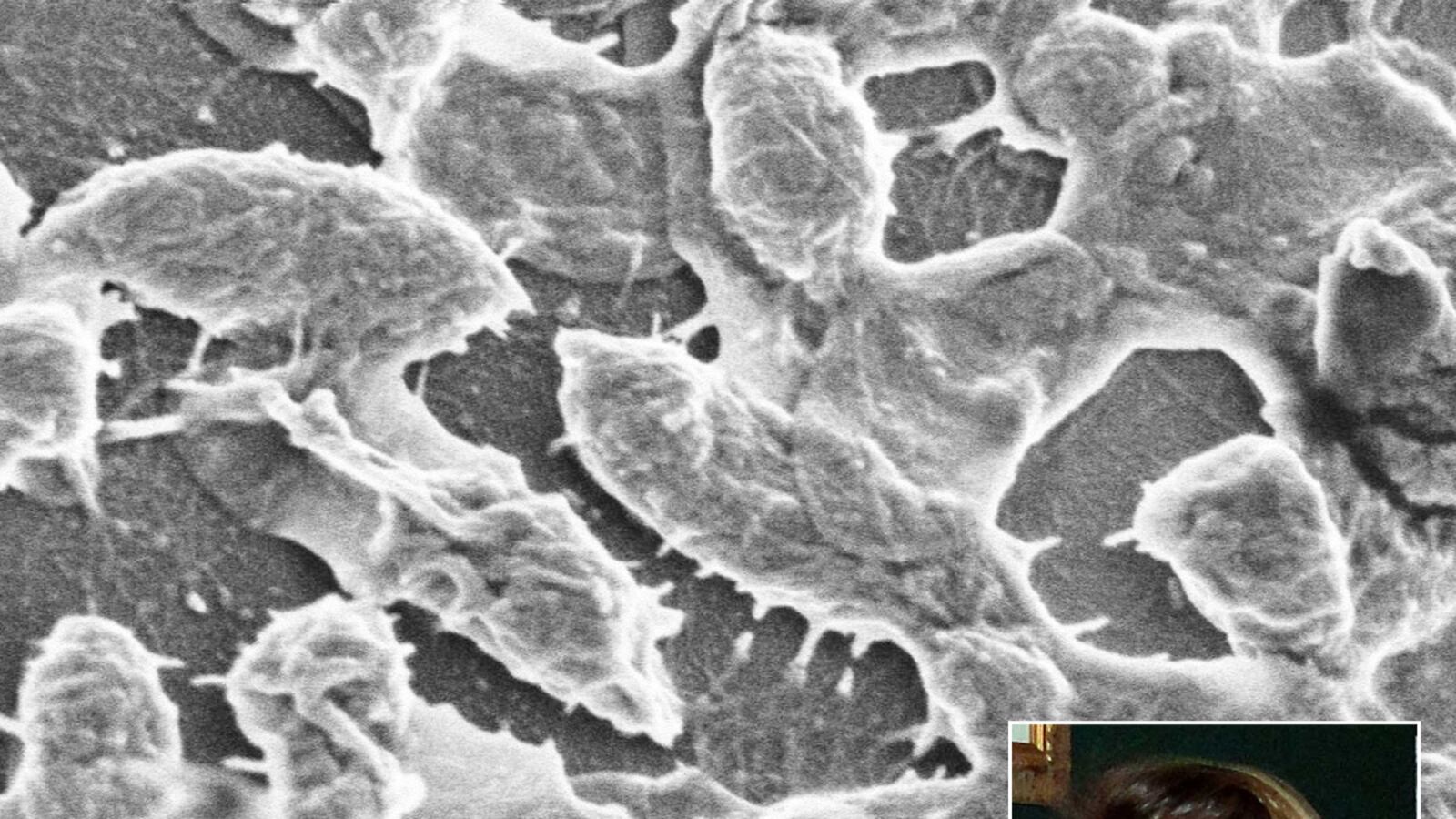

The treatment for necrotizing fasciitis almost inevitably involves immediate, aggressive surgery because the infection is caused by bacteria that have penetrated deeply below the skin, and into the spaces surrounding the body’s muscles. Surgeons must open up the muscle fascia—a procedure called debridement—and use a scalpel to scrape out all the infected tissue. Typically, they also will cut out some of the surrounding viable tissue to be sure they’ve completely removed the infection.

Helgesen got lucky. Although the operation was aggressive, he needed only one. Many patients, like Aimee Copeland, must endure multiple operations, and even amputations.

Helgesen’s infection, as it turned out, was caused by streptococcus, the same bacterium that causes strep throat. Helgesen’s doctors checked him for any external cuts or scrapes, trying to figure out how the strep had gotten so deeply into his body. They concluded, he said, that the strep already was present in his system, and when he pulled his muscle exercising, the strep evidently attacked the weakened spot.

It’s not always clear what’s causing the infection, however.

“One other perverse aspect of it is that you often don’t find the bacteria,” says Dr. Kent Sepkowitz, an infectious-disease specialist at Sloan-Kettering hospital in New York, and a Daily Beast contributor. “The bacterial load is modest, but the amount of junk that they’re producing is substantial. The bitter irony in this is that people who do poorly often have negative cultures for the bacteria at the end. It’s just that the enzymes and the cultures that are chewing up the tissue are still present. So they’ve done their dirty work—we’ve killed the bacteria—but it’s too late.”

Today, almost exactly four years later, Helgesen is back at work, now the director of his school’s athletic department. Of his experience with the “flesh-eating disease” he says, “It was hard physically but it was probably harder mentally.”

He later elaborated via email.

“You kind of feel like you are a member in a very exclusive club (that no one really wants to be a member of). If you tell someone you had necrotizing fasciitis, the first thing they ask is “what is that?” When you say you had the flesh-eating bacteria, they look at you like you have two heads.”

The surreal shock of the diagnosis is something that Gerry Ryan, 47, a management consultant in London, can relate to. Just before Christmas last year, a Baker’s cyst in Ryan’s knee burst. Doctors sent him home with anti-inflammatories and instructions to elevate his leg. But the pain continued to worsen.

“I just couldn’t move. I was hallucinating slightly. And it felt like someone had a blow torch—a naked flame—and was running it up and down my leg,” Ryan says. “The pain was absolutely intense.”

Doctors initially thought Ryan had a blood clot, but an infectious-disease doctor identified the true problem.

“I look back on it now, and it feels like it all happened in about 10 minutes,” Ryan says. “You think you’re lucid, you think you’re thinking straight.” Ryan was texting family members, reassuring him that although he was in the hospital, he was okay, not to worry.

Yet just before he was admitted for his first surgery, Ryan was told by a hospital staffer, he says, “Look I’m going to make this really simple for you. You’re seriously ill. Your kidneys, your liver, your heart, are all under a lot of pressure. You have a 50 percent chance of coming out of this alive, and a good result would be that you don’t lose your leg.”

He stayed in the hospital for weeks, having surgeries every two days, as doctors scraped away more and more of the infected tissue inside his leg.

“You’re on a roller coaster,” Ryan said.

Ryan, just like Sean Helgesen, had no external scrapes or cuts—his was another case of necrotizing fasciitis caused internally by the actions of a latent strep A strain.

Though Ryan did not lose his leg, he was in hospital for weeks. He lost a great deal of weight and strength; when he left, it was on crutches, which he was told he would need for months. The most difficult part, however, for Ryan, was getting used to the skin graft that doctors covered his wound with. “It looks alien. It looks like it shouldn’t be there,” he said. “I couldn’t touch it.”

Now, back at work, Ryan is walking without crutches. He has reduced mobility in his left leg, but says it’s “a small price to pay.”

More dominant in his thought process has been the sentiment of disbelief.

“There was an element of, how did I survive this?” he says. “I said to one person, it feels so random, it’s like walking down the street and a piano falling on your hand. It’s just not going to happen. The chances of you getting it are so random that when you come through it, you just think, I can’t begin to make sense of that.”

Often, necrotizing fasciitis occurs in a person with a pre-existing health problem—such as diabetes or lupus—that has left his or her immune system compromised, and thus less able to stave off the initial bacterial infection.

“Bad things always happen to already sick people,” as Sepkowitz puts it.

But in some cases, there are no pre-disposing factors: the patient is young and healthy—just terribly unlucky.

“This has always been an episodic, tragic, and rare event,” says Sepkowitz. “It’s not going to go away, but people shouldn’t flip out.”