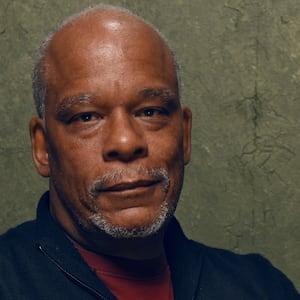

To discuss crack cocaine is to tackle a litany of bigger, intertwined American issues: racial and economic disparities; inner city poverty and crime; media reporting and sensationalism; political and legislative campaigning and action; mass incarceration and exploitation; and personal and communal responsibility. All of those topics are present in Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy. Yet at a mere 89 minutes, Stanley Nelson’s new Netflix documentary (premiering Jan. 11) bites off far more than it can chew—resulting in analysis that ranges from the persuasive to the cursory to the borderline disingenuous.

Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy employs a general chronological structure to tell its sprawling tale, beginning with the 1970s-1980s rise of cocaine, whose cost gave it an aura of being the “glamour drug” of the rich and powerful. That made it inaccessible for most lower-income Black Americans, whose dreams of using coke, the film contends, were spurred on by movies like Scarface. However, things took a turn when dealers began distilling cocaine into crack, a cheaper and more potent variant that became an immediate substance-abuse sensation. Before long, entire urban communities—which were already struggling with mounting unemployment, poverty, and crime—were being decimated by the scourge of crack, which was perpetuated by those young men and women who saw an opportunity to profit off others’ suffering, and became instant-millionaire dealers.

“Freeway” Ricky Ross, Corey Pegues, and Samson Styles are three such crack-dealing moguls featured in Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy, and their candid commentary proves one of the film’s highlights, offering a window into a world where individuals were motivated by the promise of immediate wealth, and then compelled to resort to heavily-armed violence to protect what they had acquired. Of this trio, Styles is the only one in the film to express remorse over the fact that his actions directly hurt his own community; Pegues and Ross mostly come across as proud of their self-made kingpin pasts, bragging about the clout, cash, and beautiful women they had at their disposal thanks to their lucrative positions in the underground industry. And in an unnerving moment that shows the ugliness that drove them, Pegues chuckles while remembering his cohorts taking payment for crack in the form of sexual favors (doled out in a van reserved for those private transactions) from desperate female addicts.

Crack’s particularly disastrous effect on Black women, and the cultural vilification that followed, is also addressed by Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy, as Nelson contends that reporting about “crack babies”—and, consequently, bad motherhood—was predicated on a since-disproven myth. The implication is that this slander was racist in nature, and it certainly was, though its supporting evidence comes via a scene from John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood and hip-hop songs, which seems to undermine the notion that these portrayals were only propagated by bigoted white Americans.

Contradictions like that abound in Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy, which despite its seemingly straightforward approach, boasts a scattershot collection of opposing (and frequently unreconciled) ideas. In agonized testimonials from multiple former addicts, as well as in archival news reports, crack is cast as a deadly virus that devastated individuals, families and neighborhoods, and was ignored by the population at large—and by police—because it primarily affected Black Americans. Yet the film also slams the media for overhyping the crisis (presumably in a tabloid-y way) and calling it an “epidemic.” The same goes for politicians, who are alternately censured as uncaring, as insincere for taking the drug war seriously, as fools (and/or prejudiced) for launching anti-drug campaigns—and passing ever-harsher drug bills during the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton administrations—and as failures for not doing anything in a successful manner.

That efforts such as Bill Clinton’s 1994 crime bill deserve harsh appraisals isn’t the issue; rather, it’s that Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy lacks a coherent overarching thesis about its subject, thus leading to all-over-the-place argumentation (often by talking heads who are vaguely identified as “journalist” and “historian”). One second it’s poignantly exposing the widespread wreckage caused by crack; the next second, it’s criticizing the mainstream depiction of crack as destructive, and users as falling-to-pieces victims, because that leads to negative stereotypes. While examining things from multiple angles is a worthwhile aim, there’s a frustrating sense throughout of trying to have it all ways.

Cops’ disinterest in combating crack’s infiltration into Black American communities gets brief mention, as does the police’s corrupt participation in the drug economy, be it by stealing or taking payoffs from dealers. No in-depth investigation into this is forthcoming, alas; it’s merely another of the doc’s many bullet points to be dealt with in fleeting fashion. That’s also true of the long-standing theory—first popularized by a 1996 San Jose Mercury News series of articles—that the CIA was either tacitly or actively responsible for the 1980s influx of cocaine and crack into the American inner city, through its efforts to help fund Nicaragua’s Contras in their war against the Sandinista government. A quick history lesson about the Iran-Contra scandal, married to clips of a 1996 Watts, California town hall meeting in which Black American citizens railed against then-CIA chief John M. Deutch, suggests—along with National Security Archives senior analyst Peter Kornbluh’s bold interview claims—that the U.S. government is chiefly to blame for crack’s ubiquity. (The CIA has denied this.) Unfortunately, this too is dealt with swiftly and superficially.

Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy concludes with its strongest opinion: namely, that the extreme criminalization of narcotics has, during the past few decades, led to a mass incarceration catastrophe—predominantly punishing Black Americans, even though two-thirds of ‘80s-‘90s crack users were reportedly white—that we’re still dealing with today. Nelson’s film convincingly maintains that America needs a revised public drug policy that views addiction as a health, rather than a criminal, issue. It’s too bad, then, that this discussion only comprises a small segment of the documentary, which goes off in so many different and conflicting directions that it winds up imparting little of lasting value.