Netflix makes the smartest and most obvious strategic move possible by combining two of its favorite non-fiction things—true crime and sports—with Bad Sport, a six-part docuseries (Oct. 6) about some of the craziest athletic scandals of the past few decades. A consistently gripping affair that pinpoints greed and fame as universal motivators for wrongdoing, it doesn’t deliver any novel bombshells about the depths of man’s selfishness and avarice, both of which appear to be quite boundless. It does, however, function as a telling reminder that where there’s money and celebrity to be gained, there are always people willing to skirt the rules.

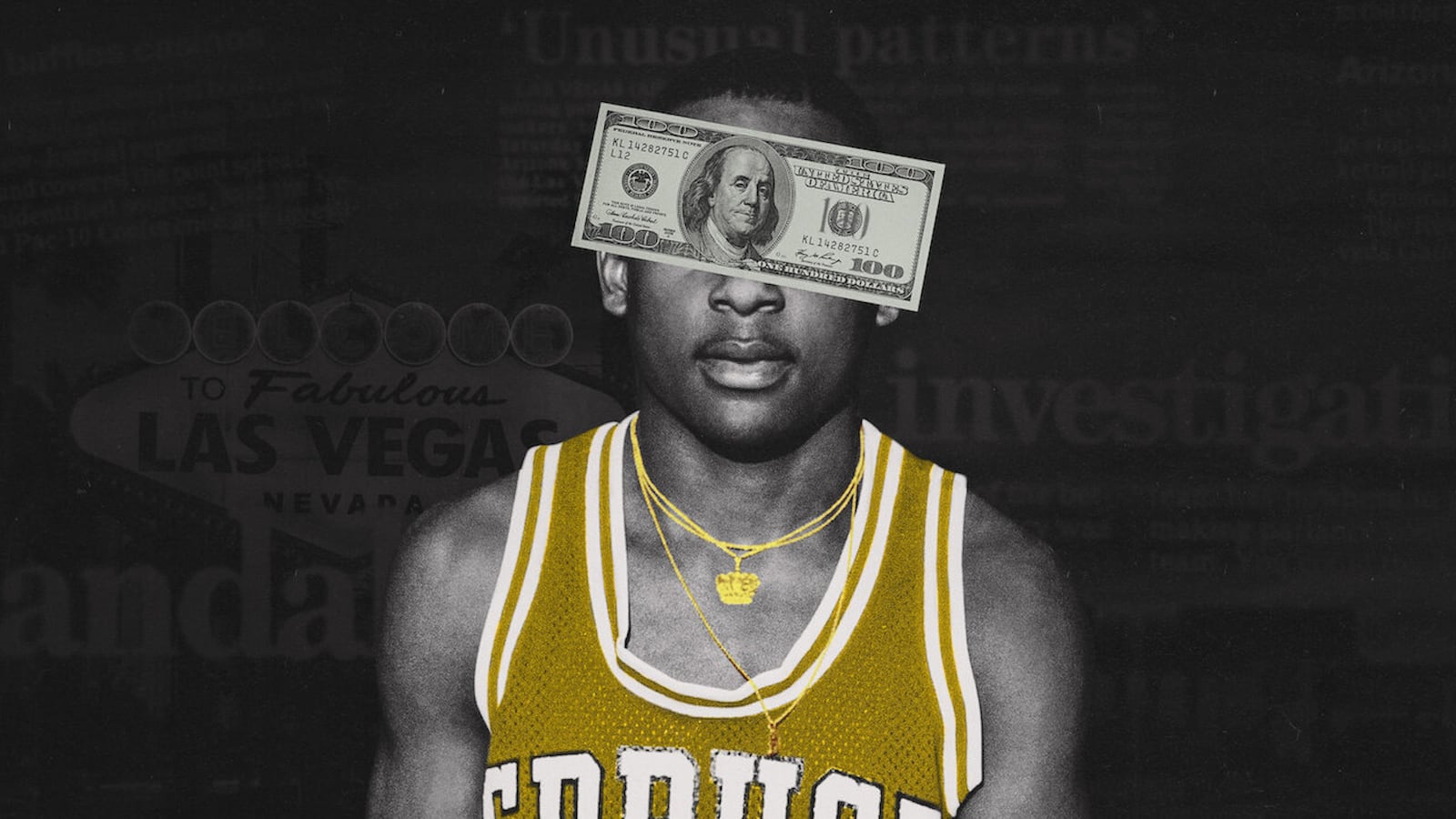

Bad Sport serves up a global cross section of sports-world malfeasance, and that begins in America with the 1994 price-fixing scheme perpetrated by Arizona State University point guard Stevin “Hedake” Smith. Despite the fact that, as a superstar senior, his NBA dreams were in reach, Smith couldn’t resist when fellow ASU classmate and campus bookie Benny Silman offered him a deal: fix the score of two upcoming games, and get $10,000 per contest. Smith not only accepted this deal but enlisted his teammate Isaac “Ice” Burton to help, and though Burton talks about how he and fellow players had to struggle financially while in school, it’s clear from their episode that what really drew them to embark on this path was a hunger for cash. Working with Silman’s partner-in-crime Joe Gagliano, who speaks openly on camera about his central role in this ruse, they initiated a system whereby Gagliano made enormous Las Vegas bets that were predicated on Smith and Burton guaranteeing that ASU won or lost by a predetermined number of points.

Just like Robert De Niro’s idiot mob henchmen in Goodfellas, Smith and Burton took their illicitly gained funds and spent madly, thereby immediately attracting the very attention they should have been avoiding like the plague. As a result, they set their downfall in motion. The same sort of idiocy is also documented in Bad Sport’s second episode about Randy Lanier, who began making a fortune as a marijuana smuggler in 1980s Miami, and decided to parlay that wealth into a professional car racing career funded by his narcotics gig. Lanier’s rapid ascension in his chosen field naturally made him headline news. Yet with that spotlight came increased questions about his operation. Since no one in the driver’s camp was especially savvy about hiding anything, it didn’t take long before Lanier started seeing federal agents lurking around every corner, and shortly thereafter, his flight from justice became a virtual inevitability.

Neither Smith nor Lanier is the least bit sympathetic, having done their dirty deeds while understanding the dire consequences should they get caught, and Bad Sport benefits from the participation of both men as well as its other subjects, who candidly and emotionally revisit their self-made ordeals. In only two cases do interviewees refuse to address a given topic: when pressed about deaths related to a smuggling mission gone awry, Lanier clams up; and in the closing installment, bookie Marlon Aronstam plays coy about his shady dealings with South African cricket superstar Hansie Cronje. Even in those specific instances, however, the truth is clear, including about the shameless amorality that drove them to do what they did. There’s little pretending on display here, as everyone featured admits to their crimes and explains their reasoning, along the way shedding a few tears about their mistakes and their regrets.

While each of its episodes are helmed by a different director, Bad Sport is a largely consistent aesthetic affair, prioritizing archival footage from the dubious games in question, as well as new conversations with principal players, over hokey dramatic reenactments and drone shots, which are kept to a reasonable minimum. The third episode, “Soccergate,” about the Calciopoli Italian football scandal in which Juventus general manager Luciano Moggi was accused of threatening referees (and choosing which ones would handle key contests), is bolstered by Moggi sitting down before the cameras and trying, largely in vain, to defend his actions as merely par for the football course. Similarly bracing is the episode five narration of Tommy “The Sandman” Burns, who spent years making a living as a henchman for the show-jumping circuit’s exceedingly wealthy bigwigs. Burns got his nickname because his main line of work was killing horses via electrocution, which made it look like the steeds had perished due to a fatal case of colic, and which allowed the animals’ owners to collect on extravagant insurance policies.

That Burns chose to betray his employers after learning that his mentor and surrogate father figure Barney Ward (a show-jumping star) planned to have him murdered is confirmation that, no matter the milieu, there’s never any honor among thieves. This familiar point is also underscored by Bad Sport’s closing episode, which tackles the match-fixing scandal in South African cricket in the early 2000s, when it was discovered that revered national team captain Cronje had opted to alter the outcomes of certain games in order to please his bookies—and, of course, to fatten his wallet. Given that Cronje was a beloved icon with no need for the extra cash, his tale turns out to be a case study in the addictive nature of large-scale profit. It’s therefore intimately related to the stories of Smith, Lanier and Moggi, all of whom similarly fell victim to their insatiable appetite for money and glory.

Pam Lanier and Randy Lanier in Bad Sport

Courtesy of NetflixBad Sport could use a little more concision; at a feature-length 85 minutes, Lanier’s chapter is particularly excessive. Still, it’s a fascinating collection of athletic misconduct perpetrated on scales both small and large, the latter of which was the case with the 2002 Winter Olympics figure skating scandal that, for a time, robbed Canadian pair skaters Jamie Salé and David Pelletier of gold medals. Salé and Pelletier, along with their Russian rival Elena Berezhnaya and her coach Tamara Moskvina, bluntly discuss Russia’s brazen attempt to pressure French judge Marie-Reine Le Gougne to swing her vote to Berezhnaya and partner Anton Sikharulidze, even though almost everyone on the planet agreed that Salé and Pelletier had earned the top prize. The continuing friction between the Russian and Canadian accounts of this incident lends their episode a bit of added verve, and suggests that when it comes to crimes of this nature, competition never completely dies.