“It was tragic, but people sometimes enjoy tragedies too,” says journalist Patricia Murray in The Alcàsser Murders, Netflix’s new five-part documentary series about the 1992 abduction and slaying of three teenage girls in Picassent, Spain. Worse still, sometimes people exploit tragedies for personal gain—including the parents of the dead.

The 1995 O.J. Simpson trial may be the most notorious example of the negative impact of the media—and, in particular, television—on the criminal justice system. Yet for definitive proof of that corrosive effect, look no further than the story of Miriam García Iborra, Toñi Gómez Rodríguez and Desirée Hernández Folch, who on the night of November 13, 1992, disappeared on their way to the nearby Coolor nightclub. Friends said the girls planned to hitchhike to the hotspot, and a witness claimed she saw them get into a white car populated by a number of men. A frantic search ensued, to no avail.

Two months later, their buried bodies were discovered by a pair of beekeepers in a remote mountainous region known as La Romana, after one of them apparently spied the Mickey Mouse wristwatch of Toñi, still attached to her handless forearm.

Director Elías León details these initial events via a rapid-fire mix of archival footage, overlapping imagery, hand-drawn animation, maps, text, and scenes of himself and others retracing the trio’s final steps and revisiting the crime scene. It’s an approach that comes off as a bit wild and aggressive. Nonetheless, even amidst its initial barrage of information and talking-head interviews, The Alcàsser Murders’ early going maintains constant focus on the faces of its murdered subjects. Seen in old photos that came to decorate posters produced to aid the search, Miriam, Toñi and Desirée are empathetically humanized by the series.

That turns out to be vital, given that their horrifying end became immediate fodder for a voraciously sensationalistic TV machine. As soon as his daughter Miriam went missing, Fernando Garcia turned to the media. The attention he courted quickly spiraled out of control, leading to a ratings battle between two rival shows—Quién Sabe Dónde and De Tú A Tú—that reported nightly on the case. Coverage became ubiquitous, and then outright pornographic, culminating with a De Tú A Tú episode the day after the girls were found, during which the grieving families sat on stage, weeping and raging, as footage of them first hearing the news was replayed, and poems of the dead were re-read by their siblings—all in between breaks for cheery car commercials.

Milking suffering for bigger audience shares, these TV “news” segments were their own form of abuse, not to mention mind-bogglingly inappropriate and repugnant, They were also immensely popular, and it wasn’t long before Alcàsser, a tiny enclave of 8,000 residents, was transformed into a virtual production set. At the center of this maelstrom, by choice, was Fernando, who took a liking to the spotlight and fashioned himself a noble crusader in the fight to uncover what had happened to Miriam and her friends. Insights were soon forthcoming from the area surrounding the burial site, where fragments of paper containing the name Enrique Anglés gave detectives their first lead.

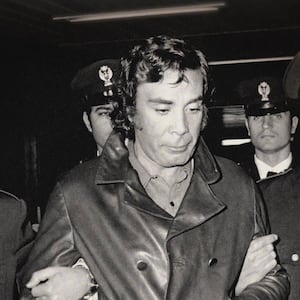

That clue led to Enrique’s brother Antonio and his friend Miguel “the Blond” Ricart. When the former fled authorities (he’s never been seen again), Ricart—who owned a white car—was left to answer for Miriam, Toñi and Desirée’s demise. He did, confessing to participating in the kidnapping, rape and murder of the girls at a nearby hut at the behest of Antonio, who by all accounts was a terrifying tyrant. Though there was almost no forensic evidence to bolster his account (DNA samples and fibers weren’t a match), Ricart knew certain details that were only corroborated by the girls’ subsequent autopsies, thereby making him a prime suspect.

Ricart, however, kept changing his story, eventually claiming he’d been tortured and pressured by cops to confess. As if that didn’t muddy the waters enough, Fernando embarked on a media-blitz campaign—accompanied by his shady partner-in-sleuthing Juan Ignacio Blanco—to argue that Ricart was innocent, and that the girls were the casualties of a larger plot involving some of the country’s elite. Were the real culprits members of a Satanic cult? A deviant sex maniac group that violated and dismembered girls for their own sick pleasure? And were “big-toothed animals” and cannibalism somehow involved? These crazed conspiracy theories were incessantly trotted out by Fernando and Juan on TV (often opposite other trial experts), and were embraced by many, in the process turning the entire affair into a three-ring circus.

Multiple portraits, all of them awful, emerge from The Alcàsser Murders: of a hellish TV landscape that treated tragedy as titillating entertainment; of a law enforcement department that failed to properly handle a high-profile case; of hucksters eager to fabricate and slander to maintain their prominence (see: Juan getting caught lying, on-air, by an ex-police officer); and of a father driven mad by loss and sorrow. In its final installments, the series recounts how Fernando, while promoting one outlandish hypothesis after another, stole the police case file so he could publicize autopsy photos and other graphic images on TV. And furthermore how, following Ricart’s carnivalesque trial and conviction, he set up a foundation to help those in similar situations—only to offer no real services and keep monetary donations for himself.

Television celebrity is a corrupting force in this true-life tale, compelling people to lose sight of their morality, and common sense, in the pursuit of attention. Even decades later, Juan still teases the series’ director and producer with a mystery tape that reportedly shows powerful bigwigs attending the girls’ autopsy—verification, he says, of his and Fernando’s version of events. It’s one final callous, pathetic instance of someone peddling lies in order to use Miriam, Toñi and Desirée’s deaths for their own gain. The Alcàsser Murders exposes these figures (and their TV enablers) as the most heartless sorts of profiteers. And in doing so, it makes a heartfelt plea for justice for male-victimized women everywhere—and, also, for far greater media responsibility.