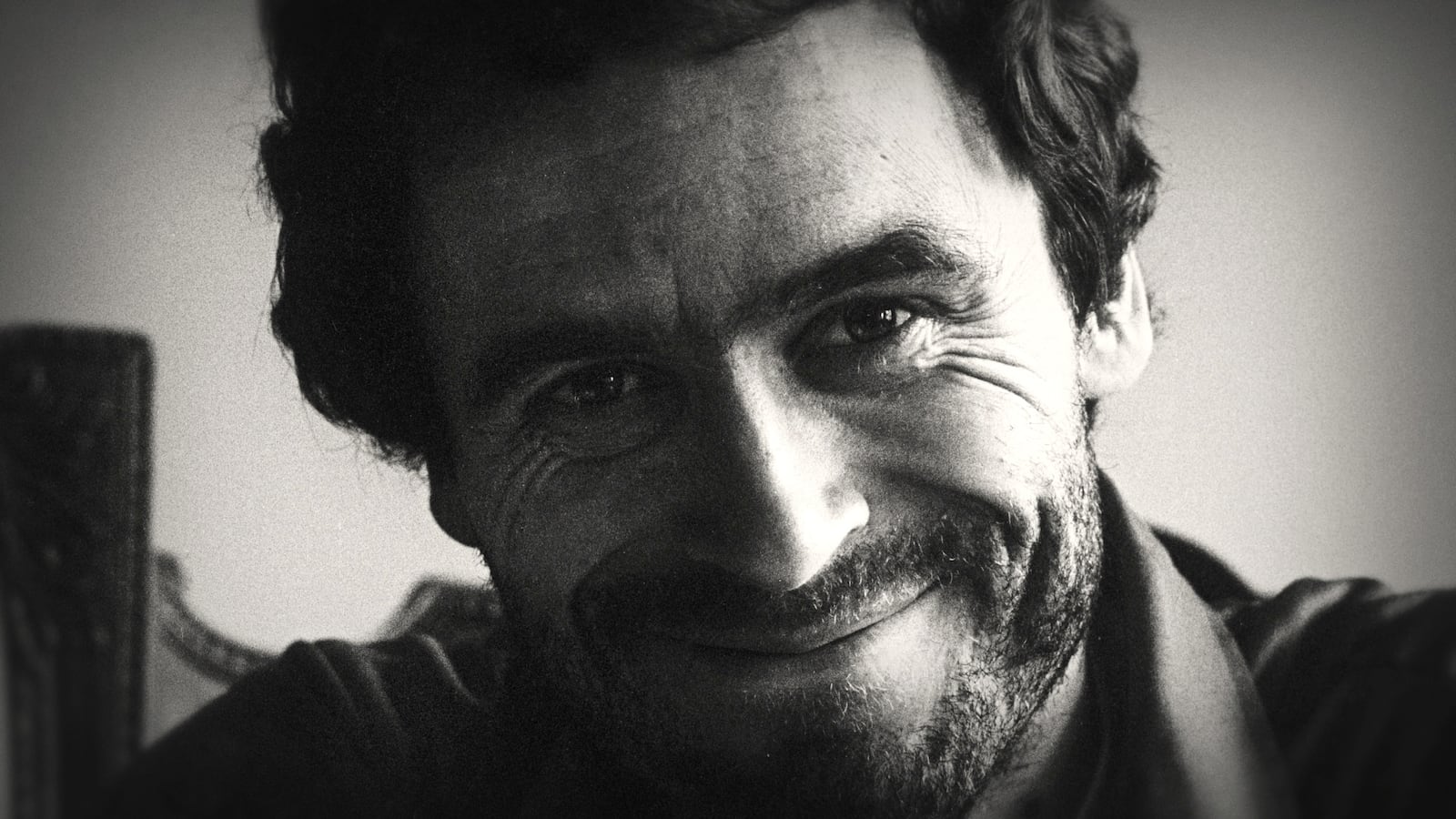

Premiering at Sundance later this month, the Zac Efron-headlined Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile will dramatize the 1970s reign of terror perpetrated by Ted Bundy, America’s most notorious—and possibly most prolific—serial killer. Yet as underscored by Netflix’s new four-part documentary series Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, which comes from the same director as Efron’s forthcoming feature, there’s no substitute for the real thing.

Helmed by Joe Berlinger (Paradise Lost), the streaming service’s latest binge-worthy non-fiction effort—which goes live on January 24—hinges on 100 hours of Bundy interviews conducted by journalist Stephen Michaud in 1980, shortly after Bundy landed on Florida’s death row. Those previously-unheard conversations are the foundation upon which Berlinger builds a stirring recap of the infamous killer’s upbringing, carnage and prosecution, which spanned numerous states, resulted in over 30 official deaths, involved two separate prison breaks, and ended with a trip to the electric chair on January 24, 1989. It’s a look inside the mind of a true sociopath who carried out his slayings with maximum brutality and no remorse. He was, in a sense, the prototypical serial killer, redefining our darkest fears about man’s capacity for cruelty—even if, decades later, we’ve never seen another fiend quite like him.

Those hoping for seismic bombshells from Michaud’s tapes will, it must be said, come away somewhat disappointed by Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes; Bundy refrained from confessing until three days before his state-sanctioned demise, when he copped to 30 killings—a figure that, many agree, may actually be as high as 100. Nonetheless, there are fascinating insights to be gleaned from the reporter’s conversations with the infamous psychopath (aided by Michaud’s editor, Hugh Aynesworth), whose good looks and middle-class stature (he was an intelligent law student with political aspirations) helped mask the madman lurking within. Bundy remains the reason we have Hannibal Lecter-type fictional bogeymen, since no other serial killer has quite married homicidal rage (born in part from women-related adolescent hang-ups, such as the discovery that he was an illegitimate child) with boy-next-door charm and cunning intellect.

In the early going, Bundy and Michaud’s sit-downs focus on the former’s childhood and college years. Always careful to pivot every story to his own advantage, Bundy portrays that era as borderline idyllic, casting himself as an athlete, outdoorsman, and sociable wannabe class president with numerous friends. It’s a telling first sign of his deviousness, given that in newly-recorded chats with people who knew him at the time, Berlinger makes clear that Bundy was anything but an affable average Joe; rather, he was a “have not” who “just didn’t fit in,” a phony who dispensed “a lot of blowhard talk,” and a “social outcast” who had a fondness for doing things like setting “tiger traps” (covered holes in the ground with sharpened spikes at the bottom) for unsuspecting peers.

Bundy, it’s apparent, wants Michaud to pen a “celebrity bio” of him, but the reporter has other things in mind. After failing to get his subject to open up about the horrific murders he committed in California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Colorado and Florida from 1973-1978—some of which also involved necrophilia—he lands upon an inspired idea: asking Bundy to talk about the crimes in the third person, from a “what would such a killer have done?” perspective. It’s a brilliant strategy that affords Bundy the chance to speak from a disassociated distance. And it pays instant dividends, compelling the convict to open up about his twisted mindset, both with regards to his homicidal acts and the motivations and impulses that preceded and followed them.

What follows are Bundy’s admissions that “women are merchandise,” that his relocation from Seattle to Utah, where he joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, was driven by a desire to rehabilitate himself into a “sound, stable, law-abiding individual,” and that, because people are creatures of habit, you have to change distinctive elements of your life in order to create new identities—a process he claims is “not terribly difficult.” During the last of these comments, Berlinger delivers a rapid-fire montage of images—women, skulls, cars on the road, squirming cells under a microscope—that concisely make cause-effect connections between Bundy’s theories and reality. Moreover, he provides a chilling window into the man’s psyche during passages in which Bundy describes how he stalked victims, why he disposed of corpses in the Taylor Mountains (answer: so animals could consume the bodies, serving as his personal “garbage disposal”), and his desire to return to the scenes of crimes, and to leave evidence there that was unrelated to the killings in order to throw investigators off his trail.

The Ted Bundy Tapes captures Bundy’s ability to “snow people,” be it friend Marlin Lee Vortman or long-time girlfriend Elizabeth Kloepfer, while carrying out his heinous atrocities, which were all successful save for his attempt to dispatch Carol Daronch, who narrowly escaped his clutches. Furthermore, it gets at his canny manipulation of the law enforcement system itself. Recognizing that cops’ cross-state communication and information-sharing was meager at best, Bundy made his way from the West to the East Coast with relative ease; without fax machines (much less the internet) at their disposal, the police simply took forever to connect the dots. His ability to break out of custody on two separate occasions, and then to hijack legal proceedings by serving as his own lawyer, only further emphasizes the pitiful state of America’s criminal justice institutions in the ‘70s (when investigators were just coming to grips with the entire serial-killer phenomenon), as Bundy exploited shortcomings and loopholes to prolong his defense—and his life.

The further it proceeds, the less Berlinger’s doc relies on Michaud’s tapes, instead leaning on new interviews with acquaintances, lawyers, experts and detectives, as well as a wealth of archival material—such as footage of Bundy’s initial trial, the first to be broadcast on TV—to impart, among other things, his narcissistic love of the spotlight, his mental instability, and his calculating cold-bloodedness. It’s a comprehensive portrait of a seemingly average individual who gave new meaning to the term “evil,” ably living up to the description “the Jack the Ripper of the United States”—and one made all the more unforgettable by its autobiographical narration from the monster himself.