This story was published by the Marshall Project, a nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization covering the criminal justice system.

Nearly a year ago, Nevada death row inmate Scott Dozier asked to be executed, telling a state court judge he would forego his appeals. A doctor deemed Dozier, who was convicted of the 2002 shooting and dismemberment death of 22-year-old Jeremiah Miller, competent to make the decision. But a problem arose: The state had no drugs to carry out a lethal injection.

Keeping with a recent trend of pharmaceutical industry opposition to the use of their products in executions, the drug manufacturer Pfizer ordered its distributors not to sell midazolam and hydromorphone to prisons. Nevada solicited bids for those drugs from suppliers and received zero offers.

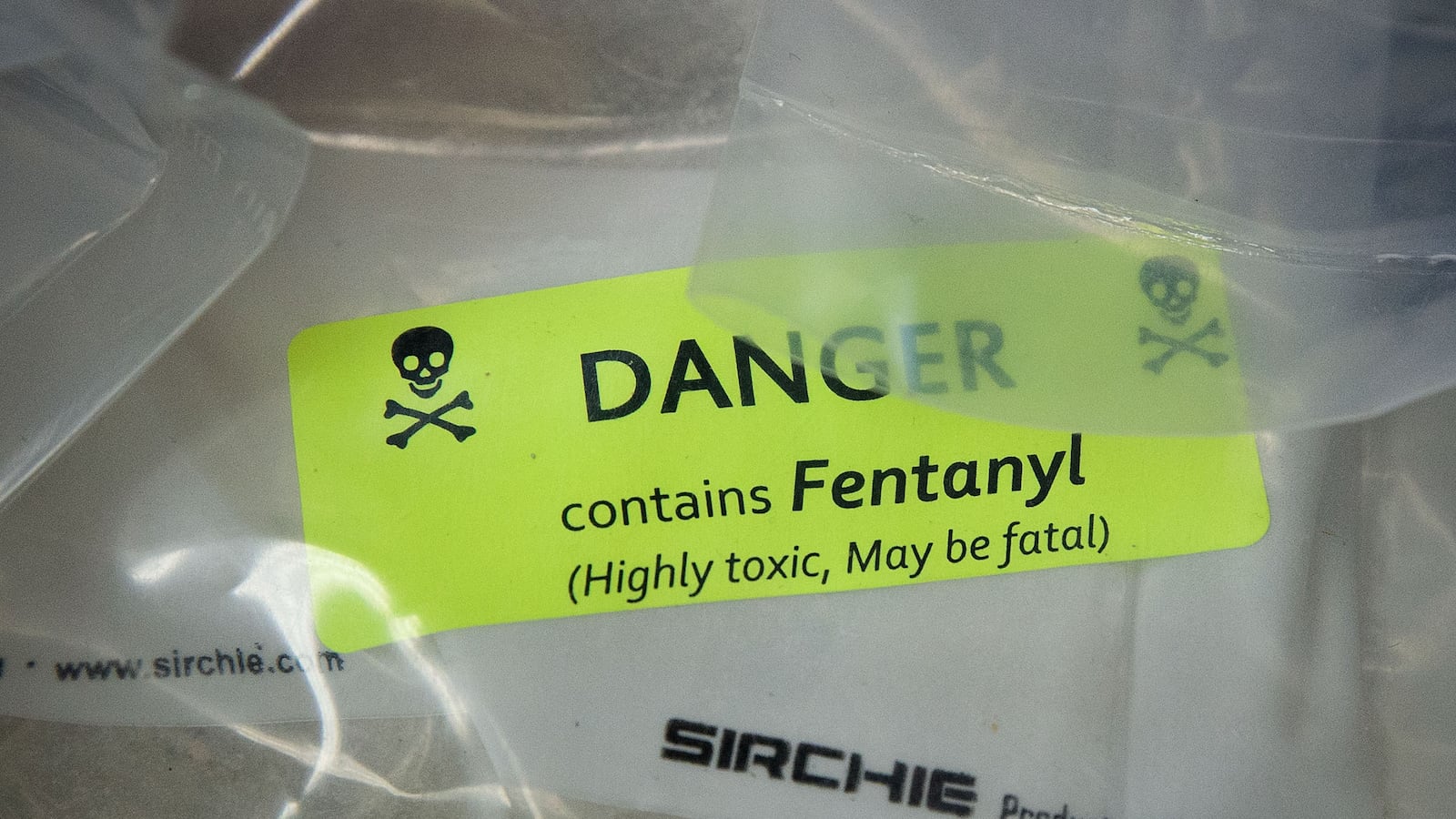

Earlier this month, Nevada officials announced a solution in the form of a new drug combination, which numerous experts say has never been used in a U.S. execution. At Dozier’s execution on November 14 — the state’s first in more than a decade — he will be injected with fentanyl (the well-known opioid), diazepam (the sedative better known as Valium), and cisatracurium (a muscle relaxant that causes paralysis).

Though the U.S. Supreme Court has declared that some pain during an execution does not violate the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, the new combination is sure to revive debates over how executions are carried out.

Much is still unknown. Brooke Keast, a department spokeswoman, said in an email the full protocol — which may include the order of the drugs, who will administer them, and who will witness the execution — will be released in the coming weeks, and that the drugs were “suggested” by the state’s Chief Medical Officer John DiMuro. DiMuro declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

Several medical professionals say there is no obvious explanation for why these drugs were selected. “It doesn’t make much sense; you don’t need Valium if you have fentanyl,” said Susi Vassallo, a New York University professor of emergency medicine who has written on lethal injection. Valium “makes you sleepy,” and can kill in large doses, but fentanyl also brings about unconsciousness without pain, and the drug’s deadliness is well-known, having caused thousands of overdose deaths around the country in recent years.

The potential problems will come with cisatracurium, which is related to curare, a paralyzing agent first discovered in South America, where indigenous people used it to poison the tips of their hunting arrows. Fentanyl can stop the heart, but it is short acting and will need to be given in a massive ongoing dose, because otherwise the prisoner may wake up. If he does, the cisatracurium will mask his consciousness while also potentially giving him the sensation — unobservable by witnesses — of being unable to breathe. “People who have recovered from it have said that they couldn’t breathe, and they knew they were suffocating,” Vassallo said. “The paralytic is only going to disguise whether the fentanyl is being administered properly.”

It is for this reason, she said, that the American College of Veterinarians forbids the use of paralytics when animals are euthanized.

The fentanyl and diazepam “may be trying to block the experience of suffocation,” said Joel B. Zivot, an Emory University anesthesiologist who has served as an expert witness in legal challenges to execution protocols. “The fentanyl takes away pain, and the Valium takes away anxiety. Both drugs are limited in their ability to do that, and of course neither is designed to block the pain or anxiety of death. So that’s just a show.”

“This is not actually science,” he added. “It’s not actually medicine. It is a grotesque impersonation of those things.”

Such analysis may play some role in forthcoming legal battles, which have often followed announcements of new drug combinations. Nevada public defenders are demanding in court that the state give them more information. A hearing is scheduled for September 11.

Dozier himself is not concerned about the possibility of pain. “If they tell me, ‘Listen there’s a good chance it’s going to be a real miserable experience for you, for those few hours before you actually expire,’ I’m still gonna do it,” he said in court recently. The state attorney general has argued that this renders moot any legal challenges on his behalf, and that opponents of the method would need to offer an alternative.

Scott Coffee, a Clark County public defender, argues that the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment is not only about Dozier’s interest. “What if [the method] was Ajax and peanut butter, or dismemberment?” he said. “Dozier could say it’s okay, but there would still be a public outcry.”

The gradual restriction of drug supplies has led multiple states to turn to new drugs and combinations, which have in turn led to visible agony among prisoners in Arizona, Ohio, and Oklahoma. The Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that some pain does not make an execution cruel and unusual punishment. “While most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote in Glossip v. Gross. “Holding that the Eighth Amendment demands the elimination of essentially all risk of pain would effectively outlaw the death penalty altogether.”

Nevada bought its drugs from Cardinal Health, a wholesale pharmaceutical distributor. Company spokesman Corey Kerr responded to a list of questions about the drugs by writing in an email, “We hold ourselves to the highest standards of accuracy and safety and have robust controls in place. We follow every manufacturer’s specific instructions to ensure the safe distribution of their products.”

Numerous pharmaceutical manufacturers have opposed the use of their drugs in lethal injections, but it has not been made public which companies produced these drugs. It is inevitable that reporters and activists will start looking for the sources. “It’s pretty troubling that Nevada has responded to the industry opposition to the use of ‘traditional’ execution drugs in executions by coming up with an entirely untested, experimental, and dangerous new protocol,” said Maya Foa of Reprieve, a British human rights organization that works with drug manufacturers to cut off supplies for executions.

In the meantime, New York state comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, who manages the state’s Common Retirement Fund, an investor in Cardinal Health, requested that the company report on its efforts to prevent their drugs from being used in executions. "Association with executions puts the company's reputation at risk and opens it to legal and financial damage,” DiNapoli said in an email. “We invest the state pension fund for more than 1 million active and retired public workers and I am duty-bound to protect their investment portfolio from risks like this.” DiNapoli has filed similar requests to other pharmaceutical companies.

The cycle of new drugs, legal challenges, and questions of supply is not the first and surely will not be the last of its kind. Zivot, the anesthesiologist, sees this round as further proof that the public should realize it is impossible to conduct a “humane” execution. “If the state is inclined to execute, it might be the time again to take up hanging, the electric chair or the bullet,” he wrote in a 2013 column for USA Today. Nevada is one of two states, along with Utah, that has carried out an execution by firing squad, in 1913, and was the first state to utilize the lethal gas chamber, in 1924.

Dozier, for his part, prefers the firing squad. “That would be the way to go,” he told a friend, “if it was up to me.”