Can one fall in love with the most evil man in history and yet not be evil oneself? What was it like effectively to be Adolf Hitler’s mistress for 13 years? Did Hitler and Eva Braun have sex, or might she have just been his “beard’? Did she have any appreciable influence on him, and thus on history? Was she anti-Semitic, and did she know about the Holocaust? Who was this woman, about whom there are so many conflicting theories but next to no actual evidence, who died—the day after their wedding—as Mrs. Hitler?

These are just a few of the fascinating questions that the diligent and fluent historian Heike Görtemaker addresses in easily the best biography of Eva Braun so far written, yet even she cannot do more than make informed guesses at their answers, because all the correspondence between the two lovers was destroyed at the time of their joint suicide in the Reichschancellery bunker in Berlin on April 30, 1945. The couple had few surviving intimates and confidants, most of whom were unlikely to be truthful in post-Nazi Germany anyhow. Moreover, the only biography written with the help of Eva’s parents and siblings, by a Turkish journalist named Kerin Gun in 1968, provided no sourcenotes.

In that Eva was hausfrau of Hitler’s Bavarian home, the Berghof at Berchtesgaden in the Obersalzburg Mountains, from 1935 onwards, she knew all of the Nazi hierarchy. She showed utter loyalty to the man she loved, taking the deliberate decision on March 7, 1945 to go from Munich to Berlin to die with him (though not against his orders, as had been previously thought). She tried to keep his spirits up right to the end, throwing parties for his birthday and their wedding day. Yet at the heart of this book is a massive void, where Eva Braun’s personality should be. Small wonder that the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper dubbed her “a historical disappointment.”

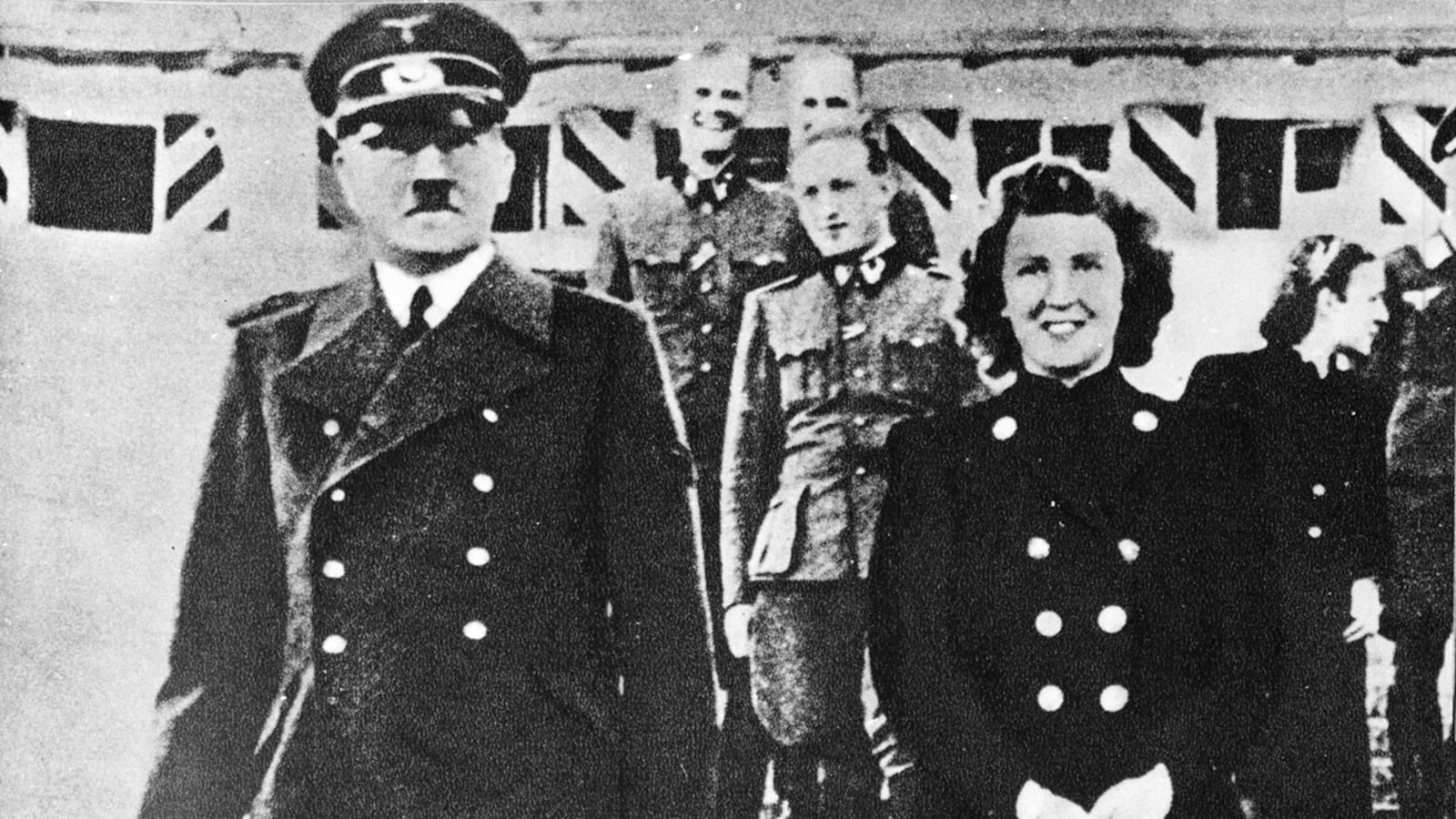

Because her existence was a state secret until the very end of the war, there is next to nothing publicly written about Braun in her lifetime, and Hitler’s utter devotion to his vertiginous career meant that she actually saw relatively little of the führer in their decade and a half or so as a couple. He insisted that when foreign dignitaries visited the Berghof she stay in her room upstairs, and even when the couple visited Rome in 1938 they stayed in different hotels. This book could have been subtitled “Life without Hitler.” Only publicly acknowledged as one of his secretaries, Eva sometimes had to join crowds in order to get a glimpse of him and he would studiously avoid being seen speaking to her in public, although he would sometimes pass her envelopes full of cash.

Here’s what we do know, or at least can legitimately infer from the sources through which Görtemaker has painstakingly trawled with a conscientious and rightly skeptical eye. Born in February 1912, the second of three daughters of Munich schoolteacher Fritz Braun, Eva was “young, blonde, athletic, fun-loving.” Her parents divorced in 1921 but then remarried the following year, probably for financial reasons. By 17 she was “a young woman of average abilities from a conventional lower-middle class family” when she answered a newspaper advertisement for a traineeship in the studios of the photographer Heinrich Hoffmann. Like many other young Germans of the day, she liked jazz, fashion, movies, travel, and sport, as well as the novels of Oscar Wilde (at least till they were banned when her boyfriend came to power).

She was utterly uninterested in politics—she never joined the Nazi Party—so when she was introduced to the 40-year-old Hitler by Hoffman in the photo shop one evening in October 1929, she didn’t recognize him as the rabble-rousing orator who had recently spoken to 16,000 people at a Munich rally. Hoffman made it harder for her by introducing Hitler as "Herr Wolf"—his Nazi nom de guerre—before sending her off to the local restaurant for beer and sausages, but at the end of the evening Hitler offered her a lift home in his Mercedes.

Boy meets girl, in this case one 23 years his junior, and over the next two years Hitler, whose HQ was only a street away from the photo shop, took Eva to movies, operas, and drives in the country. He had Martin Bormann check that there was no Jewish blood in her family, and let Eva attend party meetings under the guise of “official photographer.” Eva’s elder sister, Ilse, worked for six years as a receptionist for a Jewish doctor, even living in his house, until just before he was forced to emigrate to New York in 1938, whereupon Eva found her a job as a receptionist for Albert Speer. Their youngest sister, Gretl, married Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s liaison officer with the führer's headquarters, in June 1944 but within a year Fegelein was caught attempting to betray Hitler, and so he was shot in the courtyard of the bunker.

Hitler felt that he could not openly acknowledge the relationship because “I am married to the German people and their fate!” He certainly didn’t want any pressures or family obligations nor, in Görtemaker’s opinion, to “make himself vulnerable in the private sphere.” The support of women for his regime was vital and he feared that, like a Hollywood star, he would lose popularity with women if it emerged that he was no longer available. So he took his commitmentphobia to obsessive levels, and the only photo that was ever published of the couple together showed Eva sitting anonymously in the row behind the führer at the 1936 Winter Olympics. Despite one Time magazine article in January 1939, the story of the Fuhrer’s relationship was not known by the German people until shortly before the end of the war.

The relationship seems to have moved from platonic to physical in early 1932, according to Hitler’s Munich housekeeper, shortly after Braun’s 20th birthday. Speer recorded how, although any public displays of affection were rigorously avoided, at the end of the evening the couple would “disappear together into the upstairs bedroom.” The previous September, Geli Raubal, the daughter of Hitler’s half-sister Angela, had shot herself in Hitler’s flat with his Walther 6.35 pistol after Hitler had put an end to her affair with his chauffeur, Emil Maurice. Görtemaker suggests that Geli might have also had a crush on Hitler and been jealous of his interest in Eva. Whatever the truth, Eva certainly tried to shoot herself as well, in either August or November 1932, as a cry for Hitler’s attention. As her favorite playwright might have observed: to lose one girlfriend to a self-inflicted gunshot wound may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.

Hitler’s response was the opposite to that which might be expected. He told Hoffman that he now recognized that “the girl really loved him,” and he bought her a phone at her home so that she didn’t have to sleep on a bench at the office, waiting for his call. Things seem to have cooled off slightly by 1935. “Love seems not to be on his agenda at the moment,” Eva wrote in her diaries—whose authorship has been disputed but which Görtemaker counts as genuine—and she probably feared the relationship was going nowhere. So she staged a second suicide bid in May 1935, this time with sleeping pills. Hitler responded by buying her (through Hoffmann) an apartment five minutes from his flat, where Ilse came to live too. He also agreed to meet her (suitably star-struck) parents in August 1935 and, proving that he knew how to show a girl a good time, allowed Eva to attend the Nazi party rally at Nuremberg that September. He even ordered Angela Raubal out of the Berghof, so that Eva could take over as chatelaine at the place she nicknamed “The Grand Hotel.” Since all this happened in the weeks and months immediately after Eva’s second failed suicide bid, the way to the tyrant’s heart was obviously through self-violence.

“The more important the man,” Hitler would say in front of Eva and her friends, “the less important the woman.” Yet Eva happily put up with remarks that for most women would seem like intolerable rudeness, because she of all the German Volk had been chosen by the world’s most powerful man as his lover. There is no reason to suppose they didn’t have sex: Speer never doubted it; Hitler’s friend Max Amman spoke of “occasional intimate relations” between the couple, and Hoffmann said the relationship “took a definite shape” in 1932, as Hitler indulged Eva “the way anyone indulges a lover.” One thing that Eva did do for Mankind, in retrospect, was that—so far as we know—she never got pregnant.

In September 1938 Hitler bought Eva a house in Berlin, without her having to attempt suicide this time, and in his will that year he left her 12,000 marks per annum for life. (It is the only surviving document in his writing that mentions Eva, except the will that he wrote the night before his suicide, in which he also had nice things to say about his mother-in-law. Two years later, Eva’s father Fritz told an Allied denazification panel that his daughter “would never have entered a relationship with Hitler if he had been a bad person,” as brave a remark for December 1947 as it was moronic.)

Eva saw relatively little of Hitler during the war, which she largely spent at Munich or the Berghof, while he was at the Wolfsschanze in East Prussia for more than half the time, from where he would phone her at 10 p.m. most evenings. When they were together she would often take film and photos of him with their godchildren and friends’ children, doubtless a subconscious expression of her desire to have children by him. Hitler was very good with small children (except the millions he killed). Otherwise, Eva spent the Second World War skiing, swimming, gossiping about petty scandals, taking a visit to Italy, reading celebrity magazines, and enjoying the rest of her utterly trivial existence, as her lover set civilization aflame. The secrecy surrounding her very existence meant that she didn’t even get stuck into doing good wartime deeds, like her Allied counterparts Clementine Churchill and Eleanor Roosevelt. Goebbels called her “well-read” in his diaries, but he was the 20th century’s greatest liar, and his diaries were written for intended postwar publication.

On the occasions that Hitler and Eva were together during the war, Eva was able to put a stop to his long mealtime monologues “by asking the time, or looking at him rebukingly.” Indeed there is a slight sense that he might one day have wound up something as a hen-pecked husband, an unlikely fate for the man German propaganda was hailing “the Greatest Warlord of All Time.”

Certainly, nothing became Eva Braun so much in life as the leaving of it. “Do you think I would let him die alone?” she wrote to her best friend, Herta Schneider, as she commandeered the car to take her to Berlin and that macabre-gothic final scene in the 2,150-square foot, 15-room concrete bunker 25 feet under the Reichschancellery, where she had her own set of rooms. Once there she wrote to Schneider that she was “very happy to be near him, especially now,” and “The secretaries and I are practicing with the pistol every day.” On 22 April, after almost everybody else had left, Eva told Hitler that she was staying to the end, and he kissed her on the lips. “I shall die as I have lived,” she told Schneider in her final letter, “It’s no burden. You know that.” Yet she didn’t die as she had lived, as Hitler’s mistress, because on April 29, 1945 they got married in an understandably somewhat muted ceremony. The next day, between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m., they sat on the sofa of their drawing room and she took hydrocyanic acid, a liquid as clear as water, and was dead within seconds, before Hitler both took the acid and shot himself through the right temple. They then parted ways: he straight to the seventh circle of Everlasting Hellfire; she to a purgatory to spend eternity reading Hello! Magazine and gossiping about celebrities.

“I and my wife choose death,” Hitler had written in his will, “to avoid the shame of flight or surrender.” Yet what if Eva had decided not to die in Berlin? She could hardly have been indicted for anything at the Nuremberg trials, as she knew nothing about anything and had committed no crimes. She would probably have been debriefed by the Allies, subjected to their denazification process, pursued by historians, and doubtless feted by neo-Nazis, and since Gretl died at 73 and her Ilse died of cancer at 70, it is safe to assume that Eva would have died sometime in the mid-1980s.

This well-written and well-researched book struggles to concentrate upon its subject, constantly going off on interesting tangents instead, because of the sheer paucity of information about her. The closer the author looks for Eva, the less she finds. The reason is that until Eva’s brave decision to stand by her man, there was really nothing to her.