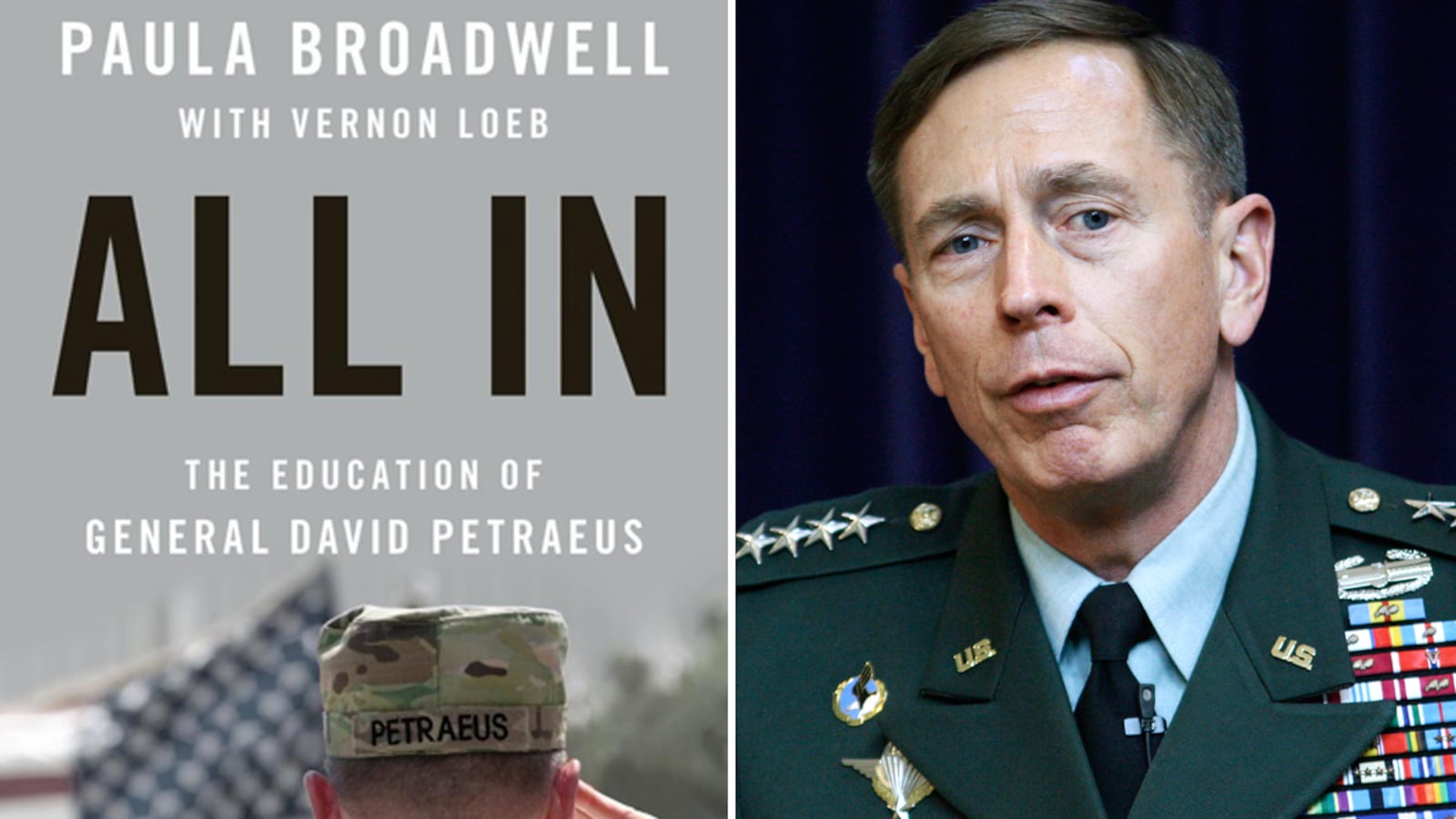

Will Gen. David Petraeus be Mitt Romney’s choice for vice president? Or Newt Gingrich’s? Should he be? Paula Broadwell’s dense biography, All In, is well timed. Politically, because of inevitable speculation about the Republican ticket in November. Militarily, because President Obama’s new budget-slashing defense strategy appears to abandon much that Petraeus worked for through the past decade of war.

David Petraeus, U.S. Army four-star retired, is the most celebrated soldier of his time. He had the rarest trifecta of military skills: the intellectual ability to marshal strategic concepts, the tactical insights to apply them on the battlefield, and the charisma and leadership savvy to organize a unity of effort by the motley coalitions he commanded. He oversaw the crafting of a manual to educate the U.S. military in the politico-military tangles of counterinsurgency. He had the moral courage to risk his career in the gambles he took to salvage the U.S. effort in Iraq. He accepted, without hesitation, Obama’s request to step down from one of the supreme posts in the U.S. military—commander of Central Command—to try to turn around the failing international effort in Afghanistan. In the 10 years after 9/11, Petraeus was deployed for six and a half of them. Now, retired after 37 years in the military, he is director of the CIA at a time when the agency is more deeply engaged in covert warfare than at any point in its history. A fanatically fit 59, he’s in the prime of his powers. Nobody thinks the CIA will be his last challenge. But vice president?

Broadwell was well placed to capture the complexity of the man. She is herself something of an all-American superwoman: West Point graduate (and subsequently an instructor there), major in the Army reserves, Ph.D. candidate, mother of two, company executive, serious athlete. Petraeus has always been a superb talent spotter; Broadwell’s combination of brains and intensity caught his attention and persuaded him to give her unmatched access. (When Petraeus and his personal staff flew out of Kabul for the final time last July, Broadwell was aboard the Gulfstream.)

For hard-core students of counterinsurgency, Broadwell’s study is essential—if depressing—reading. She focuses on Petraeus’s year in Afghanistan, from July 2010. Her day-by-day account of what he did conveys, better than anything I’ve read, the unremitting grind and relentless attention to detail that it took to achieve even a fragile hope of progress in Afghanistan. As a trained soldier, Broadwell also went out on patrols. She captures in vivid detail the tensions and sometimes horror of warfare in Afghanistan, where any track may be mined (and probably is) and villages can be so honeycombed with booby traps that it’s perilous even to venture into them.

Yet Petraeus himself remains oddly elusive. Broadwell’s access came at a price. As she says, Petraeus believes in “the mask of command”: the overriding importance of the image that a military leader must present to his troops—and, in our media-saturated era, to the world at large. If Petraeus permitted his mask to slip in front of Broadwell, it seems to have done so only in off-the-record moments. On topics where Petraeus wishes to be discreet, Broadwell is discreet.

This is especially true of Petraeus’s relations with the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama. Broadwell occasionally distances attributions by sourcing observations to friends or colleagues. But it’s always clear that the views reflect Petraeus’s own, as far as he was willing to disclose them. Usually, he was not—or at least, not for use. Nor does her account suggest that officials in either White House were willing to speak frankly to her.

That is a real loss. The core narratives of Iraq and Afghanistan, especially in the later stages of either war, were not essentially military. The governing decisions—goals, strategies to attain them, resources to devote—were political, resulting from struggles in Washington and within the Army. Throughout the past decade of war, Petraeus was an increasingly important player in these. But Broadwell reveals little—and nothing I spotted of importance—that hasn’t already been published.

Thus, recounting the White House debates in fall 2009 about future strategy in Afghanistan, Broadwell acknowledges relying on Bob Woodward’s revelatory Obama’s Wars. (The single unguarded comment by Petraeus in Broadwell’s book—his remark, after those endlessly circular White House discussions of Afghanistan policy, that “they’re fucking with the wrong guy”—comes from Woodward. Broadwell records Petraeus’s “displeasure” that one of his staff had leaked this. The remark hints interestingly at Petraeus’s frustrations with the political process in Washington. Broadwell does not explore it.)

“All In,” the book’s title, reflects Petraeus’s all-consuming approach to any task he’s given. The subtitle, “The Education of General David Petraeus,” points to Broadwell’s primary intent. Petraeus came to public notice in 2003. After seeing combat for the first time as a 50-year-old major general leading the 101st Airborne division on its thrust to Baghdad, he found himself running the tract of northern Iraq around Mosul. There, to general astonishment, he put into practice the approaches to counterinsurgency—many deeply counterintuitive to the conventional military mind—that have made his name.

Mosul was the pivot point in Petraeus’s career. Mosul was why Gen. Peter Schoomaker, then chief of staff of the Army, sent him to the Combined Arms Center at Fort Leavenworth, Kan.—hub of the Army’s thinking and preparation for future wars—with the instruction “Shake up the Army, Dave.” Petraeus’s climb from that point was dizzyingly swift.

But where, how, and from whom had Petraeus learned the skills he deployed in Mosul? Broadwell tracks his 30-year apprenticeship: lessons from experiences in Central America, Haiti, Bosnia; the influence of various four-star mentors to whom Petraeus, always ambitious, attached himself. Broadwell inserts these episodes as flashbacks from her narrative of Petraeus in Afghanistan. (The resulting structure is clumsy and sometimes hard to follow. Vernon Loeb, the experienced journalist who is now The Washington Post’s home editor, has coauthor credit.)

In her account of Petraeus’s early years, though, Broadwell’s close focus on the man again renders her account two-dimensional. Nowhere do we really learn where he fit among his peers, nor how his vision of future challenges played out within the Army. There is no shortage of published material. The Fourth Star: Four Generals and the Epic Struggle for the Future of the United States Army (2010), by David Cloud and Greg Jaffe, is the best account so far. Mark Perry’s earlier Four Stars (1989) gives the backstory to Jaffe and Cloud. Four books by Rick Atkinson, Tom Ricks, and Michael Gordon have revealed a good deal.

Yet the aftermath of those internal military debates may, ultimately, have cost Petraeus the highest command. Take the case of Brig. Gen. H.R. McMaster, one of Petraeus’s most trusted staff officers in Afghanistan. Broadwell calls him, correctly, “charismatic, free-thinking,” but describes him merely as “a rugby player with a Ph.D. in history.” That Ph.D. thesis became Dereliction of Duty, in which McMaster laid out a devastating case that the chiefs of staff during Vietnam had failed in their duty to speak truth to power—specifically, accepting presidential decisions on troop numbers in Vietnam that they privately believed would be inadequate. Anyone seeking to explain what the Obama White House saw with increasing irritation as the obduracy of Petraeus and Joint Chiefs chairman Adm. Mike Mullen, in arguing to “surge” more troops and for longer into Afghanistan than the White House wanted, has to take account of the influence of McMaster’s book on Petraeus’s generation of the military.

Broadwell confirms what has long been accepted rumor: that Petraeus hoped to succeed Mullen as chairman of the joint chiefs. Defense Secretary Robert Gates saw Petraeus as the ablest choice. (Broadwell doesn’t assert this, but sources close to Gates confirmed it at the time.) It was not to be. Broadwell records Gates breaking the bad news: “Gates … had difficult news to relay to Petraeus about the one job in the military in which Petraeus was interested—chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Forget about it, Gates said. It wasn’t happening. Petraeus’s mind whirled, even though, as he’d told a close friend, he’d had distinctly mixed feelings about the position. Nonetheless, being told it was out of the question stung.”

Yes, but why was it out of the question? It’s a reasonable inference that Gates must have broached so sensitive a topic with President Obama himself. What were Obama’s reservations? Broadwell does not explore the question. Petraeus was too celebrated a figure to be cast aside, though. Obama agreed to what Broadwell confirms was Petraeus’s second choice: directorship of the CIA.

For a military establishment now grappling with the reality of deep budget cuts—and the prospect of still more drastic surgery forced by “sequestration”—Petraeus’s legacy is ambiguous. The U.S. now has an Army skilled in COIN, to give counterinsurgency its military acronym. But COIN campaigns take years. Iraq took eight years, 4,484 Americans dead, and more than 33,000 wounded—many so grievously as to need lifetime care—all to bring a political settlement that seems more fragile by the day. Ten years in Afghanistan (cost so far: 1,886 Americans dead, more than 14,000 wounded, many equally grievously) have brought no resolution to what is essentially a struggle for political dominance between the Pashtun and the other tribes. (The sleepwalking steps by which an expedition to exterminate al Qaeda’s leaders escalated into Americans fighting an Afghan civil war await future historians.)

As Petraeus observed in his long-ago Princeton Ph.D. dissertation, the "center of gravity" in COIN is continuing political support back home. The reality is that years of war in faraway places of no commanding strategic significance will ultimately overtax America’s domestic tolerance. (If America still had the draft, Congress would have shut down the commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan years ago.)

Obama’s latest defense review, as sketchily outlined in January, appears to signal a decisive shift away from COIN. The heavy-combat baronies retain their power inside an Army hierarchy that always tended to see Iraq and Afghanistan as distractions from the conventional high-intensity warfare at which the Army is unmatched. Promotion has been spotty for officers who distinguished themselves by their imagination in either war. COIN is to be relegated to a task for special forces, its home before Petraeus’s revolution.

In Afghanistan, it’s arguable that no U.S. commander could have overcome ground truths that so uncomfortably mirror Vietnam: a divided population; a governing circle whose ravenous corruption has cost it all legitimacy; and a cross-border safe haven for enemy forces. By force of will, Petraeus was beginning to turn things around, at least tactically. But he arrived too late, and he knew it. Obama’s decisions recognized the political reality that, as in Vietnam, patience back home had run out. Perhaps the glitter of Petraeus’s career masks a tragic irony: he educated the U.S. Army to fight a kind of war for which there will never be enduring domestic support.

Let's hope Petraeus’s services to the nation are not over. Whoever wins the White House this November would be foolish to ignore his combination of brains, drive, and hard-bought experience in grappling with intractable foreign-policy challenges.

But vice president? That’s unlikely. Petraeus shies from political office. Partly this is pride. He is justifiably proud of his military accomplishments and shrinks from the prospect of having every tough decision picked over in the partisan hurly-burly of an election campaign. More fundamentally, he thinks it’s unhealthy for soldiers to brandish their military rank as a credential in civilian politics. Whatever some of Obama’s aides may have feared, Petraeus does not see himself as a man on horseback.