Modern science has a couple of tricks up its sleeve when it comes to fighting cancer. Nearly a century ago, we discovered that our immune systems can recognize and wipe out these abnormal interlopers. We’ve used this knowledge to design drugs that prevent tumors from growing and therapies that help the immune system better fight cancer.

We’ve also developed vaccines that prevent certain types of cancers by targeting viruses that mutate healthy cells. However, we’ve been less successful in creating vaccines that target cancer directly.

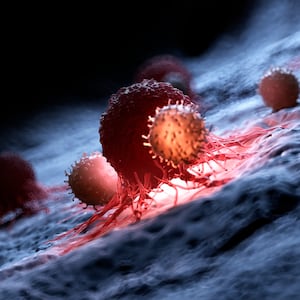

That might drastically change. In a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature, researchers headed by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston developed a cancer vaccine that prevents a tumor from evading immune cells. The vaccine recruits the immune system’s T cells and natural killer (NK) cells to essentially box in cancer cells, attacking them while also sounding the immune system’s alarm. Early results indicate the vaccine could be the first step toward creating a universal cancer jab potentially used alongside conventional cancer therapies and may prevent patients from relapsing.

“This is an impressive vaccination approach that targets a protein that is expected to be expressed on cancer cells and turns this into a comprehensive, multi-pronged immune attack against the tumor,” Dr. Andy Minn, a radiation oncologist in the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania who was not involved in the study, told The Daily Beast in an email.

Dr. Kai Wucherpfennig, a cancer biologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and lead researcher of the new study, told The Daily Beast that the vaccine relies on two proteins that cancer cells make when they’re stressed and experiencing DNA damage: MICA and MICB. These two proteins serve as a chemical beacon to the immune system leading to a cancer cell’s demise at the hands of T cells and NK cells.

Wucherpfennig said cancer cells get around this by shedding MICA and MICB from their surfaces so that they don’t trigger an immune system response. This got his team wondering if it was possible to prevent this shedding altogether.

The researchers tested their new vaccine in mice afflicted by an aggressive form of melanoma, a dangerous type of skin cancer. Not only did the jab prompt the production anti-MICA/MICB antibodies and stop the shedding, but other parts of the immune system also banded together to fight the tumor. Some of these cells were expected, like T cells and NK cells; while some were unexpected like helper T cells, which help round up antibody-producing immune cells.

This two-in-one approach is crucial for many reasons, said Minn. Most current cancer vaccines fall short of success because they are so personalized to a specific weakness or boost an individual arm of an immune response. But, tumors are wily and able to escape an immune attack by switching up their proteins, allowing them to fester incognito. Having a vaccine that targets a set of proteins shared among cancer cells means our bodies can mount a diverse and orchestrated immune attack on multiple fronts.

However, Wucherpfennig said there’s a small possibility cancers could learn to evade an anti-MICA/MICB vaccine by turning off the genes that make the proteins. That’s why he doesn’t envision the jab being given by itself.

“The way I think about combination therapies is about cutting off the exit routes for a tumor,” he said. “This vaccine could be given together with other immunotherapies or combined with other cancer vaccines to reduce the risk of escape.”

For example, if someone has prostate cancer and has undergone radiation therapy, they could potentially get the vaccine afterward to prevent any metastases—or growths that happen when cancer cells break away from the main tumor and can cause a patient to relapse in the future.

We’re still a long way off from bringing this vaccine to the clinic. Monkeys given the jab didn’t experience any side effects and seemed to tolerate it well, which means it could work well in us humans, said Minn. But future clinical trials, which are expected to start next year, are required to ensure the vaccine is safe and effective in humans. If successful, it holds the promise of helping countless patients beat their battles with cancer.