AMSTERDAM — In the voluminous letters of Vincent van Gogh, who lived on the brink of abysmal poverty and deep depression in the 1870s and ’80s, he would write from time to time about the gas lighting that he wanted and needed to keep working into the night. Candles were too dim; electric lights not yet widely available. But lighting gas, manufactured from coal and often full of impurities, could be had for a price.

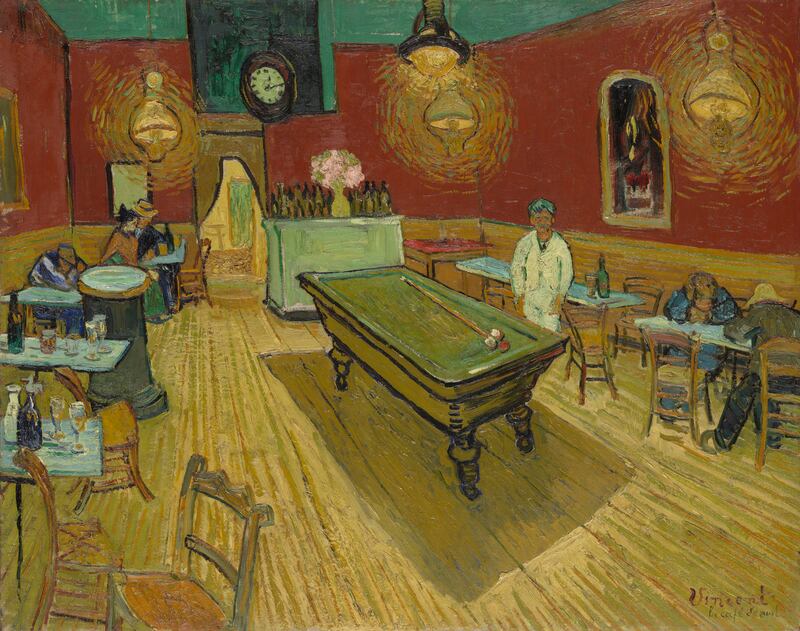

In fact some of Van Gogh’s most well-known paintings, including the famous “Café de nuit,” were painted by gaslight. And at the height of his powers, which often coincided with depths of depression, he thought it a major accomplishment to get gas piped into the house he had rented in Arles, in the south of France, in 1888.

That may have been his undoing, as a new theory about his psychological condition suggests.

Dutch chemical engineer Rene van Slooten came up with the hypothesis this year after watching a television documentary about the artist. A Dutch actor was talking about a painting of Van Gogh’s house in Arles and noted that the street had been broken up because Van Gogh was having gas lighting installed. “That’s when the alarm bells started going off for me,” Van Slooten recalls. Experience suggested to Van Slooten a new scenario that could explain Van Gogh’s illness and perhaps even his decision to take his own life at age 37. During Van Slooten’s career as a chemical engineer he’s often worked on the use of gas and the prevention of gas poisoning in industry and is well versed in the risks: “With the early gas lighting, toxins and heavy metals were released, such as carbon monoxide, lead and arsenic, metals which we now know are responsible for various ailments such as fainting, short temper, depression, psychosis and suicidal tendencies.” Van Gogh had first begun to exhibit signs of severe mental illness in Arles in 1888, about the time he had the gas brought into his rooms, although drinking absinthe and cognac certainly heightened his problems. “If the storm within gets too loud, I take a glass more to stun myself,” he wrote to his brother and patron, Theo van Gogh.

As a study in The American Journal of Psychiatry noted in 2002, Vincent soon became still more disturbed: “Feverish creative activity alternated with episodes of listlessness to the point of exhaustion. Unpredictable mood shifts of dysphoria alternating with euphoria or with indescribable anguish became more frequent.”

Contrary to the conventional lack of wisdom about Van Gogh’s work, there was nothing crazy about his brushstrokes or his color, which he intended for emotional impact that transcended the subject matter—precisely the effect he achieved, and that led to eventual recognition of his greatness. And the letters he wrote from Arles are lucid, but frightened, as he talks about what’s going on in his head.

“I am unable to describe exactly what is the matter with me; now and then there are horrible fits of anxiety, apparently without cause, or otherwise a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the head,” he wrote, “and at times I have attacks of melancholy and of atrocious remorse.”

In December of 1888, after an argument with Gauguin and at a time he was hearing voices, Van Gogh cut off a portion of his ear and gave it to his favorite prostitute, asking her to guard it for him. After that he was in and out of a hospital, eventually committing himself to a mental asylum at Saint Rémy—where, Van Slooten notes, he was still exposed to carbon monoxide fumes from gas and paraffin. In 1890 Van Gogh left for Auvers-sur-Oise, closer to Paris, where he spent the first weeks of the summer painting furiously and brilliantly before, finally, shooting himself in a field and dying in his grim, nearly lightless room above an auberge off the town square.

Van Slooten, whose gaslight theory has been widely reported in the European press, argues that the cumulative effect of gas poisoning may have been similar to that suffered a few decades earlier by the American poet and writer of horror tales, Edgar Allen Poe, and his wife Virginia. Research done on the hair of Poe, who died in 1849, and his wife Virginia, who died of tuberculosis in 1847, shows that she, at least, suffered considerable poisoning. “The level of uranium in Virginia’s hair when she lived in gas-lit New York City was very high, similar to that found in uranium miners, and approximately 15 times today’s normal level,” concludes one report on the tests.

Van Slooten published his theories on Poe and on Van Gogh last summer in the Baltimore Post-Examiner (Baltimore being Poe’s hometown). But his Van Gogh hypothesis didn’t convince everyone.

Retired neurologist and Van Gogh specialist Piet Voskuil, for instance, finds the theory highly unreliable. “Van Slooten is drawing broad conclusions based on a lot of suppositions," Voskuil says. “As a medical specialist you think about how and when you can arrive at a probable diagnosis. What Van Slooten is doing is assembling facts and arguing towards [a conclusion], using Van Gogh as a figurehead. That’s not scientific; it’s not clinical thinking. This subject just needs so much more before you can draw a conclusion like that. Where are the other patients? Why didn’t his roommates”—Paul Gauguin was one of them—“suffer the same symptoms?” Van Slooten is not shooed away so easily and seems to enjoy a little jousting. “I think he [Voskuil] is not open to the medical facts of this theory. He’s a neurologist who has been specializing in Vincent van Gogh for years, and he’s not the only one. The American Journal of Psychiatry published an entire article a few years ago about the illness of Van Gogh, in which over 30 diagnoses are listed. That’s what Voskuil bases himself on. And there am I, an outsider, who comes with an entirely new story, well” — Van Slooten barely suppresses a giggle—“he doesn’t like it very much.” Voskuil’s retort: There’s no evidence of a surge in mental patients in Arles linked to gas light during that time. “There are so many different ways to explain Van Gogh’s symptoms.” However true that may be, it does not exclude the possibility of exposure playing a role, if only as an aggravating factor. To this day carbon monoxide poisoning continues to be a silent killer. In the Netherlands alone, 10 to 20 people die each year and around 80 are committed to hospital because of gas poisoning, even though it’s natural gas, much cleaner than coal gas, that is commonly used in Dutch households for cooking, water heaters and furnaces.

“Chronic exposure,” says Van Slooten, “inhaling of small doses of gas during longer periods of time, for instance because your steam boiler isn’t adjusted right or because your furnace went out, can cause all kinds of psychological effects like: depression and psychosis, nightmares and anxieties. These symptoms are often not spotted as poisoning by physicians who ascribe them to other causes.” Voskuil remains skeptical: “Van Gogh had specific symptoms all his life. Everyone has an opinion on the matter. But research should be conducted with a certain kind of scientific validity. What was the cause? What were the triggers? Was it his use of absinthe? Why was there such a sudden beginning and end to his ‘episodes’? The theory of the lighting gas exposure has been suggested before, it doesn’t hold.” Oh, but it does, argues Van Slooten: The artist may just have been more susceptible than others, and the record of his life suggests that may be the case. “Van Gogh was depressed before, but I think it coincides with previous exposures to lighting gas,” says Van Slooten. “Like the time he had an ‘episode’ in Paris, when he stayed with his brother, who had gaslight, or when he was staying in Antwerp, where he lived and did an evening course at the academy of arts, which had gaslight, too.” About some things nobody disagrees, like the fact that Van Gogh had serious psychological issues. He sold virtually no canvases during his lifetime, and he felt he was a burden on his brother. But whatever the sources of his madness, “the storm within,” there is no question that the genius endures.

—with additional reporting in Paris and Auvers-sur-Oise by Christopher Dickey