On October 12, 1960, Bing Crosby, American icon and part owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, was a bundle of nerves. His beloved Pirates were preparing to play the mighty New York Yankees in the seventh and deciding game of the World Series, and Bing didn’t think he could take the suspense. So he did what all of us do when our team is about to play the big game: He grabbed his wife and split for Paris.

At the last minute, though, he had second thoughts–what if the Pirates won? What if someone performed a miraculous feat that would go down in baseball history? He phoned an assistant and asked him to kinescope the game off its television broadcast.

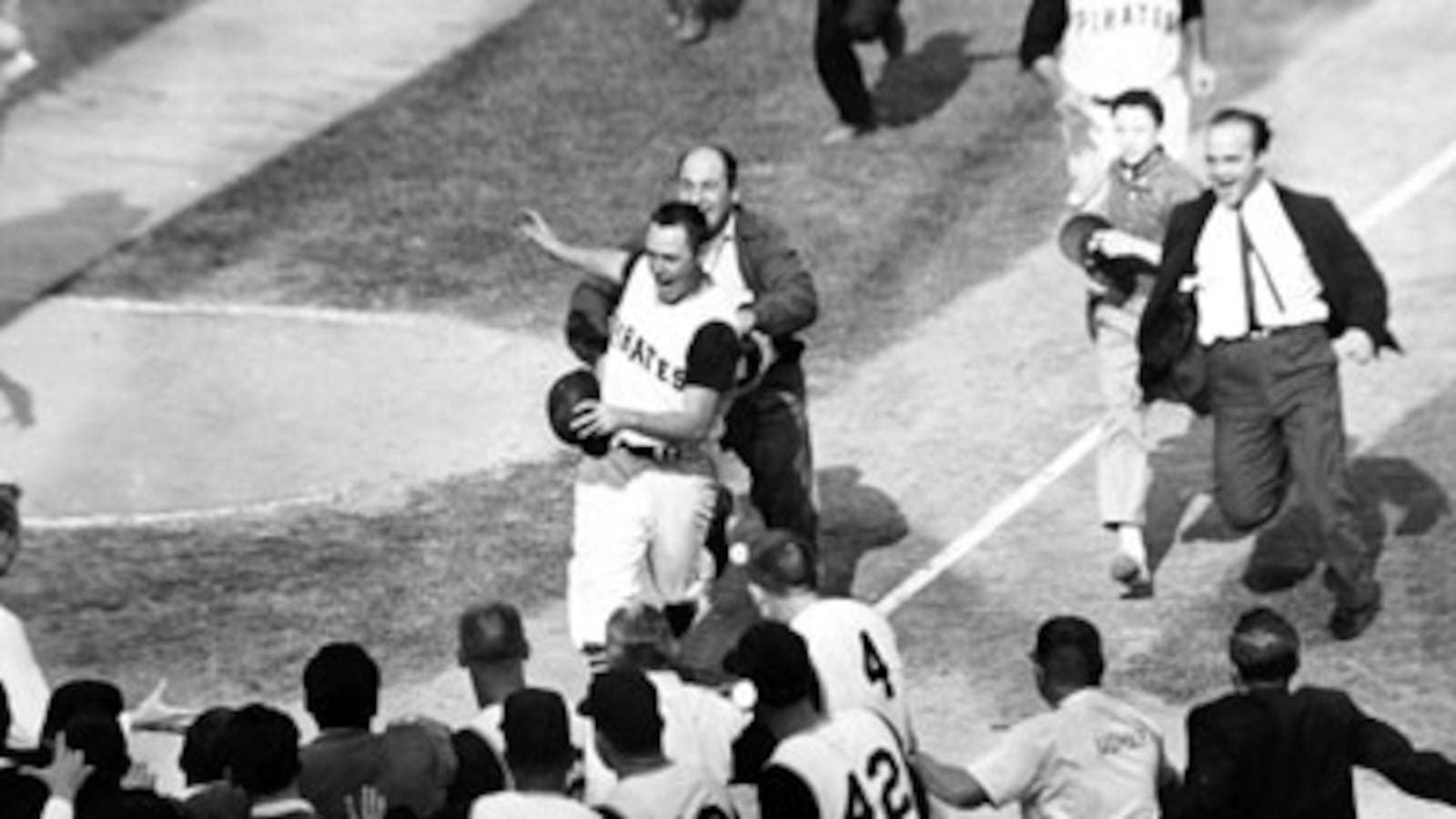

A half-century later, this decision proved to be a spectacular stroke of luck for baseball fans everywhere. In the ninth inning, with the game tied at nine all, a light-hitting second baseman named Bill Mazeroski, or Maz, as he was affectionately known to local fans, a lifetime .260 hitter who never hit more than 17 home runs in a season, took a pitch from the Yankees’ Ralph Terry and drove it more than 410 feet over the left field wall.

Yogi Berra, who was not behind the plate that day but out in left field, told me he still dreams about it. “I started to run towards the wall,” says Yogi, “thinking I could play the ricochet. Then I saw it over going way over my head and I knew it was all over. I kept right on running, all the way across the field to the clubhouse. I’ve replayed that ball a thousand times in my mind over the years–it still goes over my head.”

To baseball aficionados who are not New York-centric, it is the most dramatic home run in baseball history, surpassing Bobby Thomson’s home run in the 1951 playoff between the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants. Mazeroski’s home run, after all, won the World Series. It was the first time the baseball season ended in a walk-off home run and the only time ever in the seventh game.

For years, the only view of that home run was from a newsreel camera positioned high on the roof of Pittsburgh’s now vanished Forbes Field. Thanks to Crosby’s film, we now have two views of Maz’s shot, one from overhead but much closer to the plate, and one from centerfield which shows just how hard the 180-pound Mazeroski tagged the ball.

All this is made possible by the diligence of an employee of the Crosby estate who was rummaging through the wine cellar of the Hillsborough home to collect old films for a Crosby Christmas retrospective. Next to cans of film labeled “Going My Way,” “Road to Morocco,” and “The Bells of St Mary’s” were one labeled “1960 World Series. It didn’t take many phone calls for the treasure to find a home at MLB Network.

"We can talk forever about what the game was like fifty years ago," Bob Costas says. "This game shows us how it was played.”

“It’s in almost pristine condition,” says producer Bruce Cornblatt. “It looks like Bing watched it one time and then put it in storage.”

Wednesday night, MLB Network will broadcast the Crosby copy of the seventh game of the 1960 World Series, regarded by many as the greatest baseball game ever played. In a program recorded earlier this month at the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum at the History Center in Pittsburgh, Bob Costas and MLB Network hosted an auditorium full of Pirates fans, including actor Michael Keaton, a native who saw the game when he was ten, and former Yankees and Pirates, including Bobby Richardson, Dick Groat, and Bill Virdon–though, sadly, not Bill Mazeroski himself, who missed the program due to illness.

If it’s true, as Bob Costas maintains, that “The real golden age of baseball was the 1950s and early 1960s” then the Mazeroski game, as it is known, is a cutaway view of baseball at its apex. In 1960, says Costas, “There was still just 16 big league teams, no watering down of the talent from expansion, and though pro football was on the rise, baseball was still unquestionably our national sport. But we can talk forever about what the game was like fifty years ago. This game shows us how it was played.”

Nick Trotta, senior library and licensing manager for MLB Productions, says “We have film footage going all the way back to 1905, but only a handful of complete baseball games before 1965.” Why? “For decades, it was the home park’s obligation to record a game, and the process was very costly. It’s a shame, but the truth is that nobody knew in which games Willie Mays was going to make a spectacular circus catch or Mickey Mantle was going to hit a 565-foot home run. We have newsreels of the great World Series moments, but very few entire games.”

“Finding the Mazeroski game is a blessing,” says Cornblatt. “It’s small window of an America of another time.”

In some ways, the game was vastly different: there was no union to give the players free agency, no interleague play, and relatively few games broadcast on national TV. The highest paid players in baseball were the Giants’ Mays and the Yankees’ Mantle, who between them got less than $150,000 for the year. Today, the average salary is just under $3.5 million. About 75 percent of the players in 1960 were white, about 20 percent African American, and about 5 percent Hispanic–of which the Pirates great outfielder Roberto Clemente was the most prominent. Today, the ratio is approximately 60 white, 30 percent Hispanic, and 8 percent African American, with a sprinkling of Asian players.

Despite these differences, the game itself is largely unchanged. Batting averages for the leagues then and now are still around .260, and for all the talk of how performance enhancing drugs have inflated power, the league batting averages are around the same, .260. Allowing for the extra eight games in the schedule and the use of the designated hitter, power statistics such as home runs and extra base hitters aren’t much higher today than they were fifty years ago.

It was a time when the World Series was far and away the most eagerly anticipated event in sports. There was a single sponsor for the show, Gillette, and just two commercials totaling about ninety seconds between innings, barely enough time to get to the refrigerator and pop open a beer before the next pitch. (Today’s added commercial between innings are one of the major reasons baseball games are so much longer than they used to be.)

But viewers of the broadcast won’t get to watch those commercials. Crosby’s assistant, trying to save money on the expensive kinescope film, didn’t record between innings.

After 1960, reality set in for the Pittsburgh Pirates. The next season they finished the next four seasons the finished no higher than fourth in the National League, while the Yankees went to the World Series every year. For Pirates fans, though, the glory has never faded. “I played in a thousand baseball and softball and basketball games until I was into my forties,” says Michael Keaton, “and each time I wore Number Nine–Maz’s number. If somebody else wanted Number Nine, I got angry. When they bury me, I’ll be wearing Number Nine.”

Allen Barra writes about sports for the Wall Street Journal and the Village Voice. He also writes about books for Salon.com, Bookforum, and the Washington Post. His latest book is Yogi Berra, Eternal Yankee.