When I was a shaggy-haired youth, back in the late 1970s, New York—or at least Manhattan—was basically an archipelago of Irish bars, separated by short stretches of gum-spotted sidewalk. And it wasn’t the sort of archipelago where there’s one island over here, another one a day’s journey over there, yet another over the horizon. No, Manhattan’s Irish-bar archipelago was tight: Whenever you set sail from one bar you could usually see your next port of call down the block or across the street, with only a few, easily-skirted stretches of open ocean to worry about.

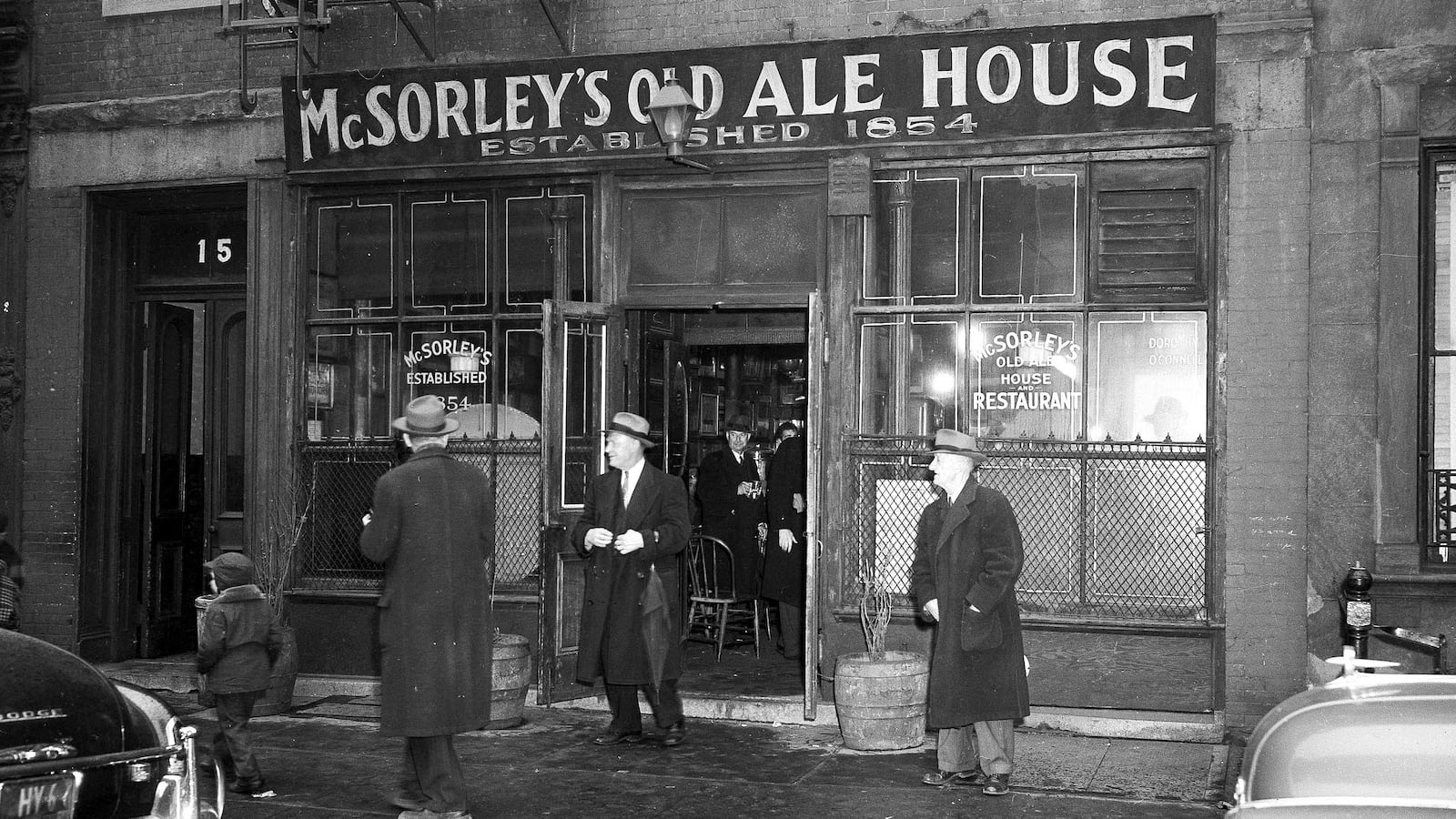

Some of those ports of call were lively, pleasant places such as McSorley’s, downtown on East 7th Street, or the Dublin House, up on West 79th, or the large and friendly Glocca Morra on 3rd Avenue near 23rd Street, or Eamonn Doran’s just-off-the-plane shebeen uptown on 2nd Avenue. Some were tight-knit and perhaps a little hostile to strangers: At McSwiggans, a couple of blocks down 3rd from the Glocca Morra, I learned quickly not to order Scotch and to put in when they passed the hat for the IRA. Others were just bars, places a file clerk or a meter reader or a fabric cutter could go and have a couple of cheap, stingy drinks and a plate of grey—but free—corned beef from the steam table. Many of those belonged to chains: There were 23 perfunctory Blarney Stones, some even within sight each other, and 28 even-less-jolly outposts of the McAnn’s empire.

Some of these bars were new, some were old, and some it was impossible to tell. McSorley’s went all the way back to 1854, while the various McAnn’s started spreading in 1945 and the Blarney Stones in 1952. Taken all together, though, they were as much a part of the city as its pigeons; New York was unimaginable without them. And like the pigeons, who always appear fully grown, the city’s Irish bars seem to have come from nowhere. When McSorley’s opened, all those years ago, did it have company? In whose footsteps did old John McSorley step when he opened the place?

Nobody has ever written a full-scale, detailed history of New York’s myriad drinking establishments, so such questions aren’t easy to answer. Various histories mention that the first St. Patrick’s Day celebration held in New York was in 1756, at John Thompson’s Crown & Thistle public house on Whitehall Street, at the very bottom tip of Manhattan. Thompson’s nickname, however, was “Scotch Johnny,” and his tavern was only Irish part-time at best. A better candidate for the first Irish bar in New York is the Fly Market Hotel, opened in 1817 by Murtagh Byrne (apparently a native of County Wicklow) on the East River side of the island at what is now Maiden Lane and Front Street. Byrne’s establishment boasted of its turtle soup (indeed, its sign bore a turtle and a partridge) and its “very superior old Irish whiskey,” which the bar would gladly make into “Hot Punch” in the winter or “Ice Punch” in the summer. Byrne’s place was evidently a popular one, but unfortunately, he was carried off by the yellow fever epidemic of 1822. His wife, Alicia, also from Ireland, carried on for a while without him, but then The Fly Market Hotel disappears from the record.

After that, things get murky. One source claims, on I don’t know what evidence, that there were “2,000 saloons… found in Irish neighborhoods by 1840.” If so, the vast majority were informal, come-and-go neighborhood places, nothing more than a room where a recent immigrant could nurse a mug of ale or throw down some cheap whiskey in the company of his compatriots. McSorley’s began as precisely such a place, and the fact that it’s still with us is as astounding a feat of beating the odds as a three-legged horse winning the Preakness. There were a few places that stood out. In the 1820s, there was Dooley’s Long Room, in the Sixth Ward Hotel, but it was more a drill-hall for militias with a bar at one end than a dedicated drinking establishment. (It even had a dummy cannon for the tipsy militiamen to heave around.) In 1835, the city’s business directory includes listings for T. Conlan & Bros. on Pearl Street, which claimed to be “stocked with the choicest liquors,” and Daniel Sweeney’s “house of refreshment” on Ann Street, in the heart of the business district. A few others turn up here and there. But there were two bars that really stood out; that became institutions.

The first of these didn’t start as Irish. The Pewter Mug, a porter-house and oyster saloon on Frankfort Street, near where you will now find the entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge, opened in the early years of the 19th century. It was a standard, three-story frame house with a very plain bar-room on the ground floor. The bar’s history was always intertwined with the politics of the city. Indeed, Aaron Burr kept a room on the second floor with its own alley staircase to meet with his cronies in secret and—conveniently—Tammany Hall, headquarters for the city’s populist Democrats, was right next door. By the beginning of the 1830s, it was kept by Francis Peckwell, a Tammany “Sachem,” or chief. From him it went to one “Major” Joe Hopkins, a Tammany hanger-on with a rowdy reputation, who in turn passed it on to Tom Hazard, who passed it to an “amiable, handsome and intelligent” widow, Mary Lynch, a friend of Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson. On her death in 1850, it fell into the hands of Tom Dunlap.

Like Mary Lynch, Dunlap was Irish-born and politically connected. In their hands, the Pewter Mug became the nexus of power for the hordes of Irish immigrants flooding into the city to escape the Potato Famine. If you wanted something—a favor, an office, anything—and could muster some votes to trade for it, you went to the Pewter Mug. There, as one observer recalled, “names were made and unmade, the laurel crown was placed upon or snatched from the brows of aspiring statesmen, and not a nomination for governor, congressman, state legislature, or city or county office could be made unless the sanction of the ‘Pewter Mug’ was first obtained.” The bar moved around the corner in 1861 and closed a couple of years later when its then owner, Billy Brown, was shot to death on the sidewalk out front of the establishment during an argument with a one-legged veteran of the war then raging.

The Pewter Mug was plain and unadorned inside and spoke more of Knickerbocker New York. Not so much the Ivy Green, another Democratic bar a few blocks away on Elm Street (now Lafayette Street), across from the Tombs—the city’s prison—on the edge of the notorious Five Points, the most dangerous neighborhood in America. If the Pewter Mug was intense, the Ivy Green was free and easy. Founded in 1844 or thereabouts by Malachi Fallon, a former Tombs warden and second-generation Irishman, the bar was famous for its rowdy fun: songs were sung, music was played, there was wrestling, boxing, and general devilment. All of the popular heroes of the 1840s and 1850s hung out there, if they were Irish, anyway. John Morrissey, the fearsome bare-knuckle heavyweight turned politician, was a regular, and so was the fearless middleweight Yankee Sullivan—indeed, once Sullivan had to shoot a man there when the man followed him into the bar and lunged at him with a knife (he survived). The police were frequent visitors. Indeed, one of them, John Stacom, was among the chain of owners who followed in Fallon’s wake after he joined the Gold Rush in 1849.

So were judges. In 1852, a certain “French Louis” was being arraigned across the street for disorderly conduct. While the clerk was taking the arresting officer’s affidavit, the judge took the prisoner by the arm and escorted him out the side door. When they didn’t return, the clerk went across the street and found them drinking together at the bar of the Ivy Green. French Louis “refused to return to the station-house until the Judge promised to go bail for him.” It was that kind of bar. The Ivy Green didn’t last much past the Civil War.

By then, however, there were a great many Irish bars in New York, enough to get taken for granted, just as they are today. John McSorley has his monument. I wish that Byrne and Lynch and Dunlap and Fallon had theirs, too; that their names would live on in New York saloons. Although development and gentrification have submerged a great many of the islands of the Irish Archipelago I found in the 1970s, there are still a great many islands left—some 2,000, by one count—with a few new ones created each year. It would be nice if among them there stood a Fly Market Hotel, a Pewter Mug and an Ivy Green. After all, every one of those 2,000 is standing on their shoulders.