The patient, Hector Campos, came into the emergency department with shortness of breath, erratic fever, and swollen, itchy ears. His wife explained that Campos had tested negative for COVID-19. “What do you think this might be?” Campos asked the chief of emergency medicine, Ethan Choi, who was similarly befuddled by the man’s symptoms.

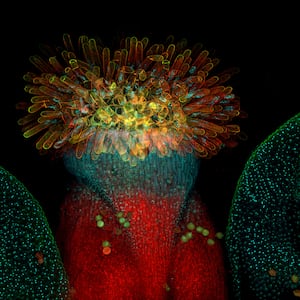

Scary, right? But it’s not real—Campos and Choi are both characters on the NBC medical drama Chicago Med. Over the course of the episode, which aired in March 2021, Choi initially misdiagnoses Campos’ symptoms as pneumonia and a bacterial infection, but a test comes back for widespread inflammation. Campos’ condition rapidly deteriorates, and the team of doctors is mystified until fellow ER surgeon Dean Archer suggests it might be VEXAS, a rare autoinflammatory syndrome. Genetic sequencing ultimately finds a mutation confirming the diagnosis, and Choi begins treating the patient.

The episode is fictional, but depictions like this one are surprisingly accurate to real-life cases of VEXAS, said David Beck, a clinical genetics researcher at New York University Grossman School of Medicine. “In terms of clinical manifestations,” he told The Daily Beast, “they’ve been spot on.” Beck ought to know: He and his colleagues first named the syndrome in a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2020. “I’ve been impressed, actually, with depictions in popular media, because [it shows] they’ve read the paper.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Even so, these representations of VEXAS syndrome tend to highlight severe cases, in part because the NEJM paper did, too. Of the 25 cases the researchers studied, 10 of the patients died from VEXAS-related causes.

But more recent research has expanded the case definition of VEXAS to include a milder side. In a paper published in JAMA on Jan. 24, Beck and his colleagues scanned genetic sequencing readings from more than 160,000 people to determine how common VEXAS syndrome really is, and how its symptoms manifest in patients. The research team found that nine male patients and two female patients in their study had mutations that caused VEXAS.

And as a result, the researchers estimated that the syndrome affects about 13,200 men and 2,300 women over age 50 in the U.S. alone.

“It’s thrilling to go from trying to understand a few patients to finding that the same genetic cause and the same disease is found in tens of thousands of individuals,” Beck said. “Not just because we know that there are many patients out there who are suffering, who don't get a diagnosis, or who don't get the treatment that can help them and just taking a step in that direction; it's also very surprising that you can still make these sort of discoveries despite all of the biomedical research going on.”

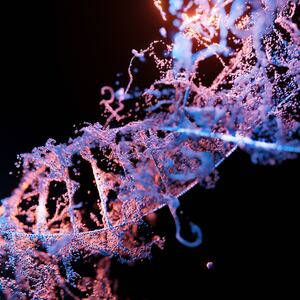

VEXAS is an acronym that stands for several key features of the syndrome. In every case of the syndrome, a patient has a genetic mutation coding for the enzyme E1. The mutation occurs on a gene on the X chromosome, which as you might recall from biology class, is a sex chromosome—men only have one, making them more prone to coming down with VEXAS. And the mutation is somatic, which means it is acquired during life as opposed to being inherited from a parent. That last feature, which gives VEXAS its “S,” is crucial: Because VEXAS is caused by a somatic mutation, the syndrome isn’t passed down and only occurs in older patients, typically over the age of 50, Beck said.

This type of research, Beck emphasized, has been made possible by recent advances in genetic sequencing that make it readily available and affordable to patients. The participants in the study all sought care at a Geisinger health care facility in central and northeastern Pennsylvania between 1996 and 2022. As part of a collaboration between Geisinger and the Regeneron Genetics Center to map genetic variation across the human genome, the participants’ exomes—regions of their genomes that encode proteins—were sequenced.

All of the 11 participants found to have mutations in the gene for the E1 enzyme were anemic and the vast majority had abnormally large red blood cells and a low platelet count—all symptoms consistent with VEXAS syndrome. Importantly, though, some of the more severe symptoms associated with VEXAS, like inflammation in the cartilage (which caused Campos’ swollen ears), were not present in these patients. This suggests that there may be a broader spectrum of severity when it comes to cases of VEXAS syndrome.

One other puzzling aspect of the study was the fact that the two women retrospectively identified as having VEXAS syndrome only suffered from the VEXAS-related mutation on one of their X chromosomes, not both. “It’s confusing for us,” since originally the researchers thought that VEXAS only affected men, Beck said. “We've been slowly recognizing more females that have the disease, and we don't understand why that is.” One phenomenon at play could be X-inactivation, a process in which one of a female’s two X chromosomes is silenced throughout their cells.

The researchers wrote in the study that future analyses will be critical to understanding the prevalence of the syndrome in diverse populations, since 94 percent of the participants in the Geisinger cohort were white.

Currently, there are no treatments for VEXAS approved by the Food and Drug Administration, but a phase II clinical trial is underway to study whether blood stem cell transplants can treat or cure the syndrome. In 2022, a team of French researchers published a study suggesting that such a transplant can lead to complete remission, but such a procedure is not without its risks.

On the research side, Beck said that scientists are still trying to figure out how a mutation in the gene that encodes E1 leads to the widespread inflammation seen in cases of VEXAS. This enzyme starts a process for a cell to eliminate proteins it no longer needs, and further research is ongoing to determine how a dysfunctional E1 enzyme impacts this process.

“If you're an older individual with systemic inflammation, low blood counts, don’t have any clear diagnosis, and you require steroids but don't have any clear diagnosis,” you should contact your doctor about genetic testing for VEXAS syndrome, Beck said.

“It may help lead to better treatments for you—and at least a clear diagnosis,” he said.