The Monday after the Watergate break-in (which was in the dead of night on a Friday), Peter Goldman went to 444 Madison Ave. to put together the early Nation story list for the upcoming issue. He was filling in for Larry Martz, the section editor, and when the Wallenda-in-charge came by to see what Nation would be offering, Goldie mentioned, as an afterthought, “We should probably do something with this wacko burglary at the DNC.” The Wallenda—along with pretty much everyone else at the time—was unimpressed. The story would be 10 days old when people saw it, he said. Peter scheduled a 200-line piece near the end of the section.

“It took us a long time to catch up with and finally overtake the competition, including, even, the Post,” he says.

Nobody knows the embarrassment of those early weeks better than me. I was at The Washington Star covering the presidential primaries and, when not traveling, pressed into the desperate job of trying to match the flood of stories by Woodward and Bernstein. At the steady, reliable Star, every important development we couldn’t source was written with a line that said the story originated in The Washington Post. This was very honest, very true to our readers, and very hard to swallow.

Newsweek was being beaten by Time, where Sandy Smith had excellent FBI sources. Washington Bureau Chief Mel Elfin went to work. He put Nick Horrock, Ev Clark, and John Lindsay on the story. He added Tom DeFrank, Steve Lesher, Diane Camper, Hank Trewhitt, Henry Hubbard, and Sam Shaffer. He hired Tony Marro, one of the best reporters in town, from Newsday. In effect, every member of the bureau was called upon sooner or later.

In the early days they played defense. Horrock would walk over to 15th Street late at night and grab the early edition of the Post and start working on any new developments. Lindsay was working on Charlie Shaffer, John Dean’s lawyer, a contact that was to pay off big. Ev Clark, whose beat was technology, aerospace, science, and all else, developed a source and event database that would serve the team well.

“We got in a few good investigative licks, but when the investigation reached institutional D.C., the extraordinary depth and talent of our Washington bureau came into play,” says Goldman. For the most part “institutional D.C.” only watched throughout the remainder of 1972 as the story simmered but didn’t boil. In retrospect there were lots signs of what Donald Segretti and the college Young Republicans, known by a colorful euphemism for rodent sexual relations. There was the patently phony letter sent to the reactionary Manchester Union-Leader accusing Ed Muskie of referring to French-Americans as “Canucks”. It turned out to be written by White House aide Ken Clawson. There was the rogue Democrat from Maryland who showed up in New Hampshire to hold a “Draft Ted Kennedy” press conference, ignored by the “Boys On The Bus” but still a distraction. The guy had gotten an anonymous envelope of cash on his doorstep instructing him to act, and like the rest of us didn’t suspect it was from CREEP, the well-named Committee to Re-elect the President. A distraction, yes, but George McGovern was winning the nomination on his own. As usual, the too-clever-by-half stuff wasn’t so important.

The break-in and the dirty campaign money, and the slush fund that paid for “the plumbers’” escapades, were crimes, though. Mike Mansfield, one of the Senate’s greatest leaders, was personally offended, and at the start of a new Congress he chose Sam Ervin of South Carolina to head a special investigating committee, On Feb. 7, 1973, the Senate voted unanimously to appoint four Democrats and three Republicans to investigate the case.

Newsweek never looked back. It had made its reputation as the go-to newsweekly when it sprinted out front during the Civil Rights struggle and then the Vietnam War. Its journalism was informed and fearless. Watergate was an opportunity to stay in the vanguard.

Goldman remembers. “The home office in Gotham was on the next thing to a war footing. Ed Kosner, Larry Martz and I, joined by Mel Elfin's disembodied voice on the squawk box, met first thing every morning in Ed's office to figure out our coverage and shape and reshape our story list. Those sessions came to be known as the "pre-meeting"--they preceded the daily magazine-wide story meetings and pretty much determined how much (or how little) space was left for non-Watergate stories.

“The intensity, and the exhaustion, of those times was like nothing else I'd experienced at Newsweek, even during the floodtide years of the civil-rights movement ... Henry Hubbard, on the Hill, had the Rodino committee [Peter Rodino’s House Judiciary Committee] wired, along with its chief counsel, John Doar. John Lindsay was tight with John Dean's lawyer; we knew (and reported) pretty much exactly what Dean was going to say in his Senate testimony before he said it. Steve Lesher brought in an unimpeachably sourced account of the Supreme Court's deliberations in the Nixon tape case. When three senior Republican senators called on Nixon in the last week and advised him to resign, two of them told Sam Shaffer who had said what, and one of them (Hugh Scott) let Sam read his verbatim notes. Those all produced major Newsweek scoops.”

Hubbard and Shaffer reported on the congressmen and senators from both parties who cried, or at least “teared up,” when they had to tell Nixon it was over.

And Newsweek protected its sources. It was standard for files to quote unnamed sources and, in parenthesis, to tell New York “NFA (not for attribution) Peter Rodino” or whomever. When Mel became suspicious that the files were being distributed a bit promiscuously, he changed the protocol. Files no longer included the names “NFA.” They simply said, for the writer’s exclusive knowledge, “NBP,” meaning “name by phone.”

The magazine did 38 cover stories in 14 months. Wally McNamee is fond of one in particular. In 1969 he had shot a series of formal portraits of Attorney General John Mitchell for a cover with the line Mr. Law and Order. Five years later the art director selected another of those portraits for a cover. The cover line was Indicted.

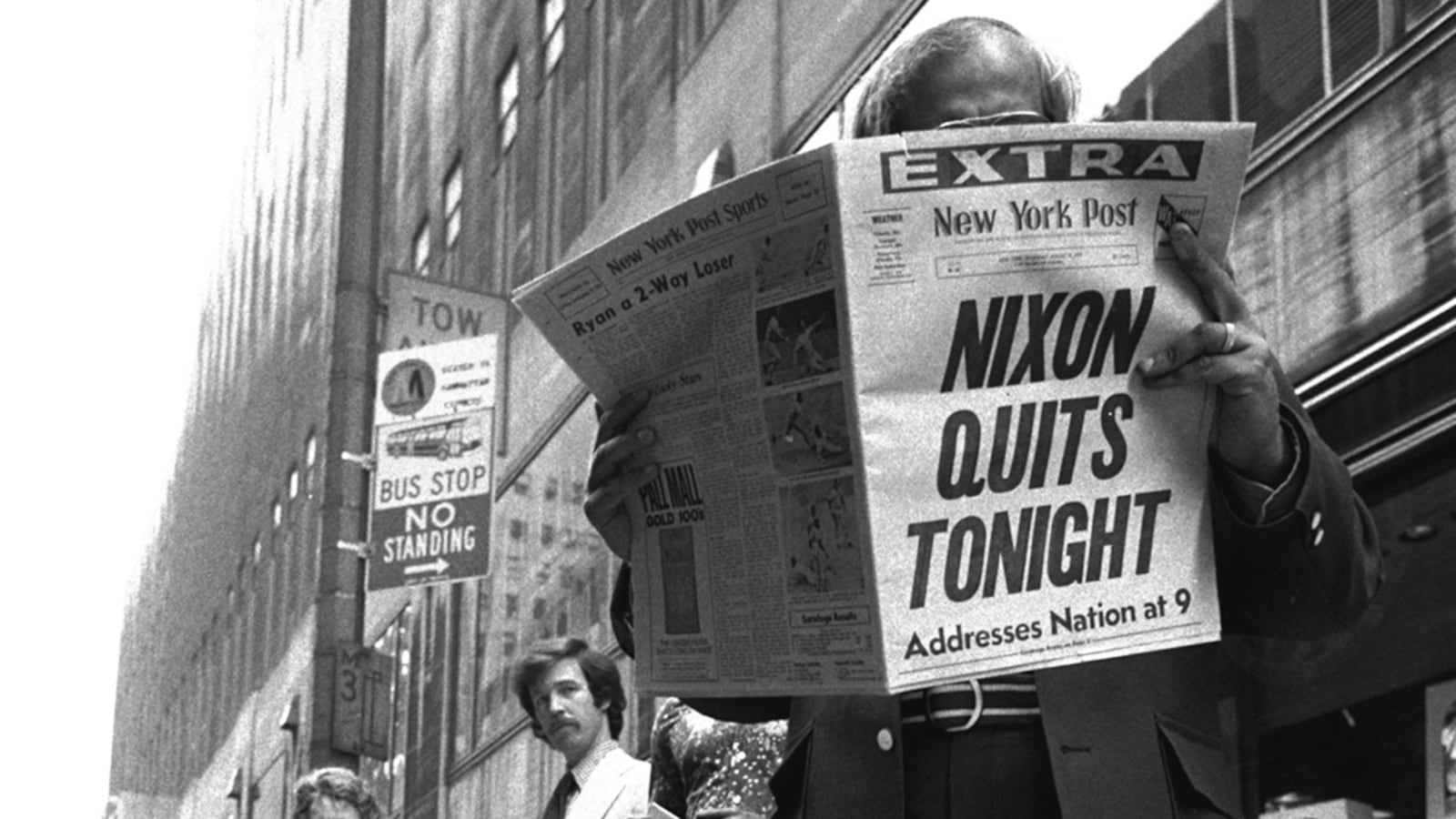

Peter Goldman wrote 34 of those cover stories—six in a row in the weeks leading up to Nixon's resignation. Anyone who has watched Peter pace the corridors, worry the details, pore over the files again, go for a swim to ease his burden and come back just as burdened, knows that the words came not easily but beautifully. He says now: “The heroes of the tale were the correspondents who brought all that tick-tock, all those inside moments, all those scoops. I told our pal Tony (Fuller) once that I was like a tailor—if our reporters came up with high-quality yard goods, I could run up a nice suit, but without reporting, I’d have been dining at soup kitchens. I was then and am now a dedicated believer in group journalism, otherwise known as the team game.”

Jim Doyle was the uncommunicative spokesman for Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski at the Watergate Special Prosecution Force. He then wrote Not Above The Law: The Battle of Watergate Prosecutors Cox and Jaworski. (1977, William Morrow). In 1976, at the suggestion of Tony Marro, Mel Elfin hired him to be deputy Washington bureau chief.