After an early career as the swaggering leading man of big studio productions, Nick Nolte is currently riding one of Hollywood’s most intriguing second acts. Once the image of the broad-shouldered, self-confident American male, he has now become a living commentary on that persona, both onscreen and off.

Offscreen, the public’s knowledge of his life is now almost totally defined by one image taken on what was likely the worst hair day in American history, the “scarecrow” picture of him shot in the hours after his arrest in 2002 for driving under the influence. Onscreen, at age 70, he has taken on a series of roles that have grappled more fully with aging and mortality than any of his contemporaries have dared, playing a series of shattered tough guys struggling to pull themselves out from under the weight of the past.

Nolte gave another signature performance this year in Warrior, as a recovering alcoholic father trying to reconcile with his two very estranged sons. Set against a backdrop of a mixed martial arts tournament, Nolte’s performance elevates what could have been a genre potboiler into a work with real emotional weight. Despite Warrior’s being a nontraditional sort of Oscar film, there is buzz the role could bring Nolte the prize that has long eluded him in this year’s Supporting Actor race.

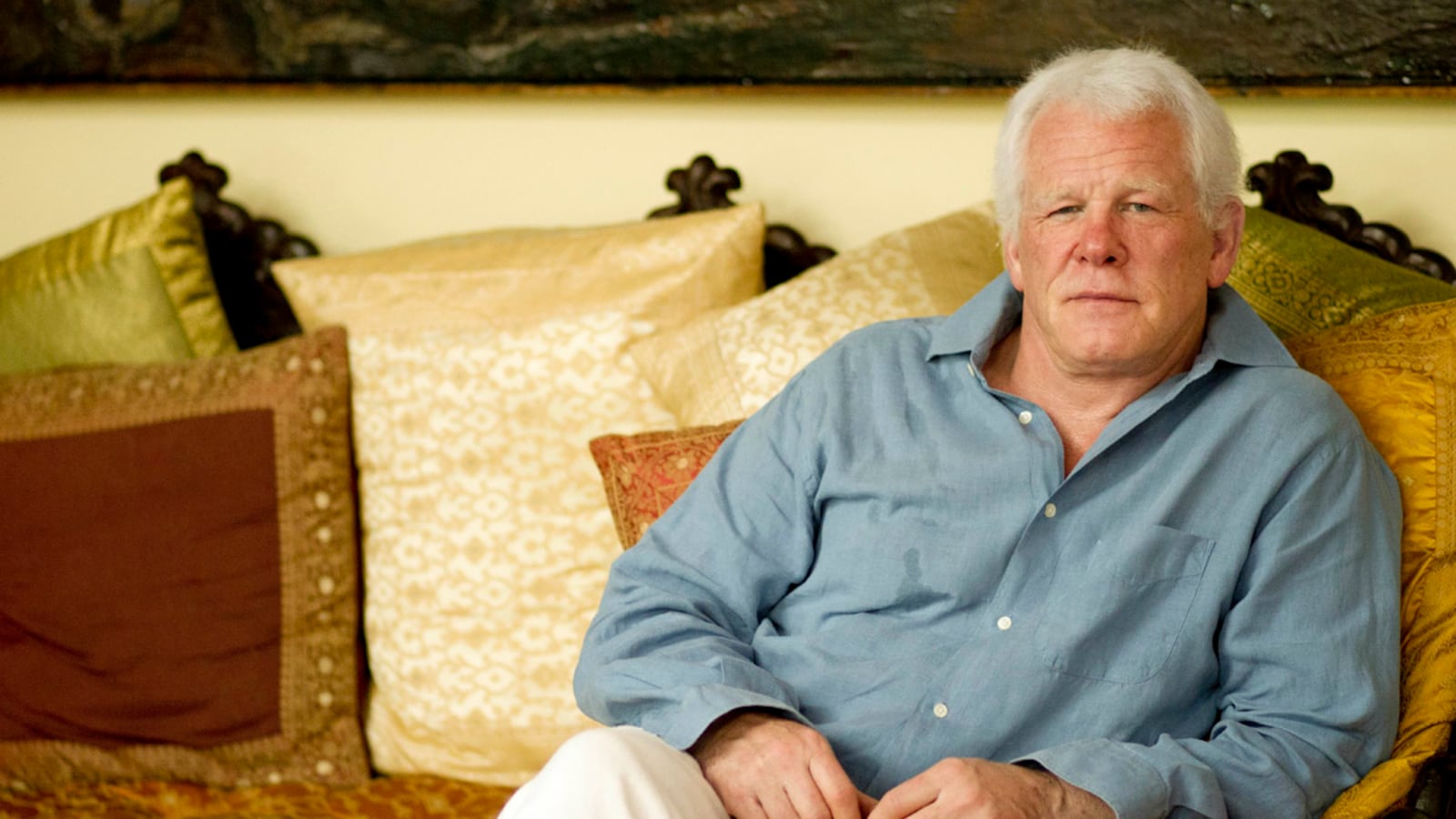

Nolte’s Malibu ranch is not where one expects to find the subject of the scarecrow photo. On the lawn, marble Grecian statues of gods and heroes are scattered like boulders. The large living room, on the other hand, seems prepared to receive the Dalai Lama’s entourage, with stacks of dark silk floor pillows, a collection of native drums, and an urn full of didgeridoos.

Nolte himself is still the tall, hulking figure of yore, but like his surroundings, he radiates an almost impossible gentleness, his trademark rasp never modulating above a lilt. He answers questions deliberately, referring frequently to those who have influenced his long career and always leaving the impression that this is a man who spends a lot of time thinking about things, who does very little just drifting with the current.

Asked where he’s been hiding lately, Nolte reveals he has not just been shut up in a cave somewhere talking to himself but has marked out a route of his own. “I’ve been busy all along,” he says. “I like to do one European film a year. I went over and did a film in Spain just a few months ago. It was all in Spanish, I was the only one who spoke English. I do French films, Spanish films. It’s beautiful. It’s the Spanish hours.”

Looking back on his career in Hollywood, he sounds almost bemused remembering the winds of fate that carried him to the heights of the A-list and now to his current place in the indie world. Of his early career, he says: “I did a lot of what I wanted to do. I got very lucky with North Dallas Forty and a few other films. They worked. Had any of them flopped at any time, that would have been it, you know, ‘He’s got to do what we say.’ But finally I didn’t think there was any more material really out there to do. I was going to have to do a series of studio films that I wouldn’t want to do, so I dropped out of it.”

“I had a funny situation,” he continues. “I was working with Terry Gilliam and he offered me Twelve Monkeys (which he was raising money for). And then I had a movie open (poorly) and he said, "I don’t know how to tell you this but last week you were on the A-list, and this week you’re not on the A-list.’ I said, ‘That quick?’ He said, ‘Yeah, that quick.’ I said, ‘Terry, well you gotta make your film. You can’t get it financed if I’m not on the A-list."

Asked how he felt about falling from those hallowed ranks, Nolte only seems bemused again. “Ah, not bad,” he says. “It was a curious thing. But I was headed for independents anyway.”

Now deep into his indie phase, Nolte says that what draws him to a project is passion: “Reading the script, if it really strikes me. I’m not one who will not work with first-time directors. Just enthusiasm. I’m looking for passion.” With age also comes wisdom to the ways of filmmaking and intolerance of its less amusing side. “If there’s going to be any chaos in a film, I won’t do it,” he says. “Because it usually destroys a film. I can see it coming from a long, long way off. And if it can’t be corrected, it’s time for me to move on. I have in the past worked with some very difficult people, but it’s only happened maybe three times. But those are miserable experiences.

“You know, it’s so difficult that if you don’t walk away feeling good about the work, you don’t have much. I’ve said this to Jeffrey Katzenberg: ‘They’re not going to put on your tombstone, “He made $20 million.” They’re going to put, “He made this great film.” It’s what you can go to your death and say, “I’m proud of that.”’ That might have affected some people.”

While he may be more sanguine about his journey, Nolte’s obsession with his work hasn’t changed. Getting the latest start of any of his generation’s major stars—he was 35 when he landed his breakthrough part in Rich Man, Poor Man—Nolte came to Hollywood from an extremely long apprenticeship on the stage, performing across the West in repertory theaters. That background still comes through when he talks about preparing for his roles. “I think Hepburn said it the best. She said, ‘There ought to be a law against actors getting married.’ And I think that’s just about right, because how do you deal with somebody who is in love with work? It always comes first. And that hasn’t changed. It doesn’t mean I won’t make sacrifices for my family. But deep down in my heart, my work is what comes first.”

Asked about his role in Warrior and parallels between the alcoholic father he plays and his own life, Nolte says: “You know, I didn’t think about that until I started talking to the interviewers. And for some reason they think that because of Affliction [his early Oscar-nominated performance]. But that was about not being able to love, it wasn’t about alcoholism at all. This one the father is an ex-alcoholic. They seem to think that’s me because my life seems to have alcohol in it. But it really doesn’t. I wasn’t arrested for alcohol. I was arrested for driving under the influence of an intoxicant, but it wasn’t alcohol.” (Nolte pleaded no contest to driving under the influence of the drug GHB.)

“But it doesn’t correlate. What’s behind drunkenness or any of these infections is a spiritual problem, and it’s usually love. In Warrior’s case, the father was so obsessed with winning that he drove his boys to not connect with him.”

When talk turns to the Oscar campaign ahead, Nolte does not recoil, as one might expect of an indie stalwart, but seems rather to enjoy the prospect.

“You know, it takes a while to sort this out,” he says. “I’ve learned not to put expectations into it. But I saw my best friend Alan Arkin…rooting for himself to get it and he got it, and I thought, ‘Well, that’s pretty cool. It was well deserved and it was all right that he rooted for himself.’”

Remembering his last time in the race, when he was nominated for Best Actor for his 1997 role in Affliction, Nolte lights up and recalls, “I had such a good time with Ian McKellen because he was up for playing this gay director [in Gods and Monsters], Ed Norton was up [for American History X], and myself. And Benigni was up. And Benigni had won at Cannes and had climbed over the chairs and they didn’t know there it was a practice routine for the Oscars.

“Before the award Ian McKellen came up to me and said, ‘I don’t care if you get it or I get it or the kid with the bald head and tattoos gets it. But if that little Italian f--- gets it, I’m going to be very upset.’ So then it was announced that Benigni got it. At the break, I looked over to where Ian was sitting and he wasn’t in his seat, and neither was Ed Norton. So I quickly said, ‘Uh, I’ve got to go to the bathroom,’ and got out just before I was locked in. I went to the bar and there they were. I came walking up to Ian and he said, ‘Nolte, I don’t know why you thought you would get it. You only play yourself.’ And Ian had just played a gay director and I said, ‘Look who’s calling the kettle black!’ And we both turned on Ed Norton and said, ‘What did you think, a bald head and a few tattoos were going to get you one?’ And we had the best damn time.

“So the Oscars don’t have to be that serious. In all reality, there are some performances out there that we don’t even know of. It’s too bad Oscar can’t honor all the great roles, but there are too many.”

Asked if after all he’s been through and with all the contentment he’s apparently found, he even cares about getting an Oscar, Nolte does a half-shrug and offers his trademark ironic smile. “You know, it would be nice,” he says. “I’m getting to the end of my life. I’m 70 now. I don’t know how long you’re supposed to live. It goes fast.”