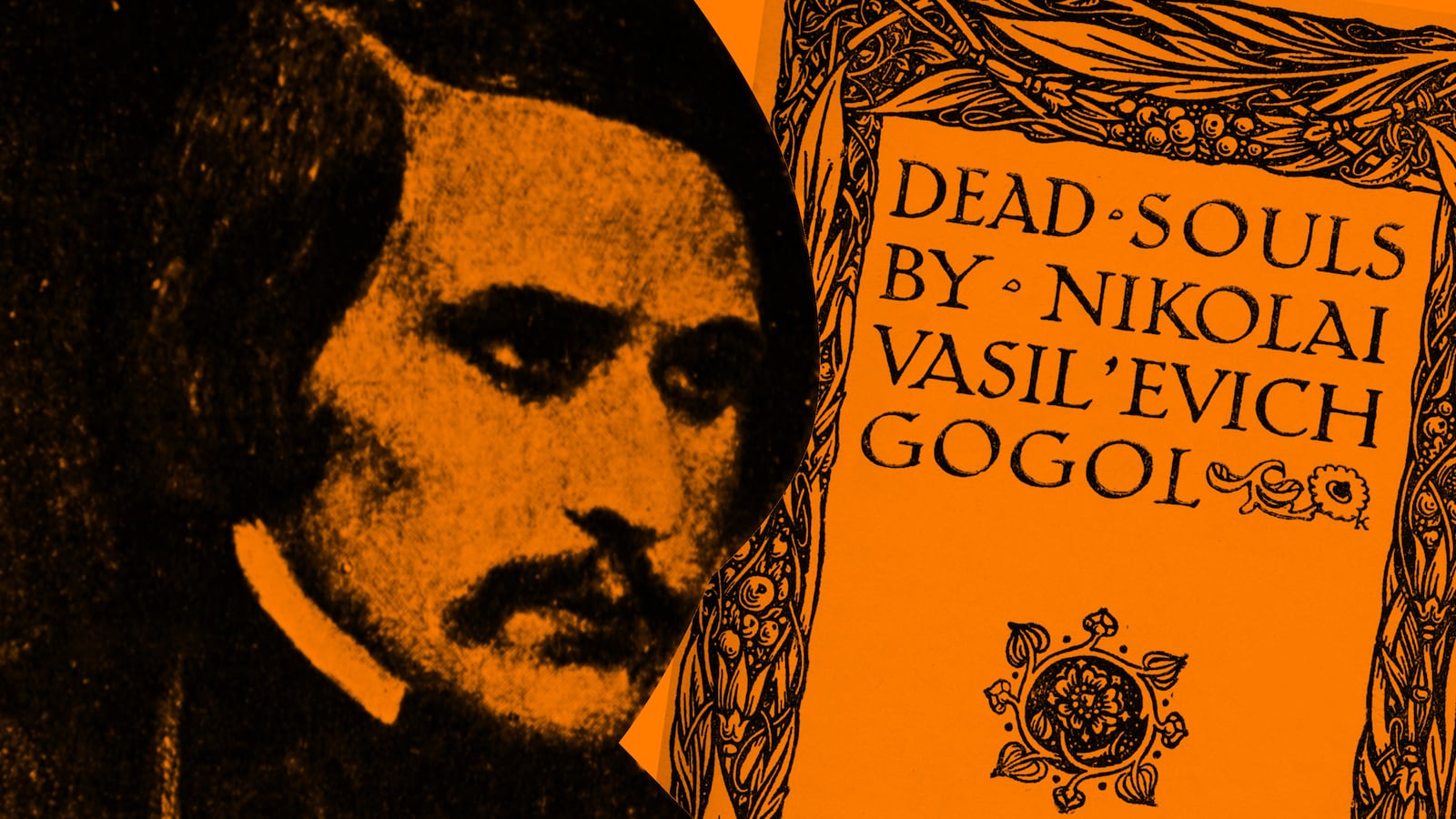

Three years after the publication of his magnum opus, Nikolai Gogol was in the midst of a spiritual breakdown. Dead Souls entered the Russian literary conversation like a shocking new fashion trend. Some people celebrated the hilarious satire as revolutionary, the harbinger of a new era in Russian literature; others hated it.

But they just didn’t understand it, and how could they? The novel was only the first part of a planned three-part masterpiece. The truth would only be revealed when that last page was written. Gogol had spelled out his intention right there in his inaugural text, explaining to the reader that the author and his protagonist Chichikov “are destined yet to tramp no small distance arm in arm along the highway; two long parts of the poem are still to come, and that is no trifle.”

But when you intend to write a novel that will do no less than save the soul of Russia, the pressure is profound. Sure, Gogol’s reputation as a Tsar of Russian literature had been solidified with Dead Souls, but that in no way lessened the stakes for what he hoped his work would achieve, namely to become the Russian equivalent of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

But on this day in 1845, as his religious tumult was tightening its grip and his poor health, real or imagined, continued to take its toll, Gogol passed judgement for the first time on his efforts to continue the satirical opus. He threw three years’ worth of work on Part II into the fire and let the flames eat away at his words.

This wasn’t the last time Gogol would condemn his efforts to the flames. The next seven years would see him wandering the continent as his spiritual and medical crises continued. He would fall under the influence of a fanatical religious figure, adopt strict ascetic practices, and make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

Through it all, he continued working on Part II of Dead Souls. But his growing distress at his own perceived failures would lead to a final act of literary immolation, one that would not only rob the world of the enlightenment he had promised to deliver in the trilogy, but would also result in the death of the master himself.

Gogol was only 33 when Dead Souls, his last great work, was published. But despite his success at a relatively young age, the troubled turn his life would eventually take had already been foreshadowed.

Born in 1809 in the Ukrainian countryside, then under the rule of Russia, Gogol showed literary talent from his early school days. After graduation, he moved to St. Petersburg where he attempted to make it as a bureaucrat, then as an actor, but failed at both. Gogol remembered his success in school, and decided he would become a poet instead.

His self-published first attempt was not well received, and, in its aftermath, Gogol went a bit crazy. He burned every available copy of his book of poems (setting a precedent for his future struggles), stole money from his mother, and hit the road to wander around Germany. He eventually made his way back to St. Petersburg and began writing on the side of his job as a lowly civil servant.

Literary success began to find him. Gogol wrote plays, essays, and short stories. He found a fan in the great Russian writer Alexander Pushkin.

“[Pushkin] always told me that no other writer has the gift of representing the banality of life so clearly, of knowing how to depict the banality of a banal man with such force that all the petty details which escape the eyes gleam large in the eyes,” Gogol wrote in a letter in 1843. “That is my principal virtue, belonging to me alone, precisely that which is in no other writer.”

When Gogol set out to write Dead Souls, his ambitions were immense. He claimed that “All Russia will appear in it!” He crafted a satire that he referred to as his “epic poem” that follows the corrupt, disgraced bureaucrat Chichikov to the countryside, where he has devised a get rich quick scheme. In those days, Russian landowners owned the serfs who worked their property and were required to pay taxes on them, even those who had died, until a new census was taken every so often. Chichikov sets about buying up dead peasants for pennies, and plans to use his new “assets” as collateral for a loan.

While not all of Gogol’s countrymen fawned over Dead Souls, some critics objecting to his portrayal of the Russian countryside and character, the book was an undeniable success and its writer labelled a master of the new Russian realism.

“Gogol was a born writer, and his minor epic is a major feast of Russian prose. It caused a sensation when it first appeared, almost all of its characters immediately became proverbial, and its reputation has never suffered an eclipse. The book entered into and became fused with Russian life, owing mainly to its verbal power,” wrote Richard Peaver in the introduction to his translation with Larissa Volokhonsky of Dead Souls.

“Do you like the novel Dead Souls? I like Tolstoy too but Gogol is necessary along with the light,” Flannery O’Connor later wrote.

The first installment of the trilogy paints the evil machinations of Chichikov and the increasingly ridiculous landowners that he meets before he is forced to flee town with the paper roster of his new serfs in hand. But the great Russian antihero was not meant to be left in sin. Gogol intended to chart his redemption in the second and third volumes of Dead Souls. The author was no longer out to simply make his name as a writer; he now saw his literary quest as a mission from God.

But this quest was too much for Gogol to handle. In The Book of Lost Books, Stuart Kelly tells the story of how Gogol once began to read his Part II efforts to a friend when it started to thunder. “God himself does not want me to read something unfinished,” Gogol reportedly replied as he abruptly ended the reading.

According to Kelly, Gogol “compared Part I to an overture for a work of unsurpassed importance,” and he told his friends that Russia was “awaiting me as though I were some sort of Messiah.”

So it’s no wonder that the pages he was producing failed to live up to his impossible standard. In 1845, he burned his first attempt at Part II and set about starting anew.

“The second part of Dead Souls was burned because it was necessary… It is first necessary to die in order to be resurrected,” Gogol wrote in a letter in 1846. “I thank God for having given me the strength to do it. Immediately that the flame had carried away the last pages of my book, its content suddenly was resurrected in a purified and lucid form, like the Phoenix from the pyre, and I suddenly saw in what disorder was what I had considered ordered and harmonious.”

In the wake of that first Dead Souls bonfire, Gogol continued to descend into madness. He went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to search for guidance in his spiritual crisis, but there was none to be found. He returned to Russia where he deepened his relationship with a fanatical priest named Father Konstantinovsky who only added fuel to his mania. Konstantinovsky, who is often described as a proto-Rasputin, convinced Gogol that much of his previous work was not to the glory of God. Under this influence, Gogol continued to strengthen his ascetic practices.

In 1852, Gogol’s obsession and hysteria finally reached breaking point. At 3 a.m. one day in February, he collected a bunch of papers from his desk and began to burn them. While the exact contents of the conflagration are unknown, it’s believed that Gogol’s efforts on Part II and Part III of Dead Souls were included along with other papers. Only a few chapters of Part II were found among the pages that survived his death.

After the job was done, Gogol retired to his bed. For nine days, he refused to eat. As if his starvation wasn’t bad enough, his doctors decided to force a medical intervention, which included bloodlettings and a series of hot and freezing cold baths.

But Gogol succumbed to his exhaustion and his illness of body and spirit. He died nine days after burning most of what remained of his unpublished Dead Souls trilogy, never having completed the work that was meant to save Russia, and maybe even himself.